In Search of the Counterfeit "Casey"

In Albert Spalding's compendium of American baseball from its origins to the early 20th century[1], baseball' s former star, future Hall-of-Famer (1939), tireless entrepreneur, and foremost impresario also revealed himself as a literary critic:

Albert Goodwill Spalding 1850-1915

Like every other cause worthy of the best efforts of writers of note, Base Ball has a literature peculiarly its own. Love has its sonnets galore; War its epics in heroic verse; Tragedy its sombre story in measured lines, and Base Ball has "Casey at the Bat."

America's National Game, by Albert Spalding (1911)

Following his re-printing of the original version of "Casey at the Bat," exposition of the origin of "Casey," and the 1892 meeting of Hopper and Thayer in Worcester--which definitively established Thayer's authorship of "Casey" to Hopper's satisfaction --Spalding turned his attention to "another poem, of equal literary merit, a parody on Macaulay's 'Lays of Ancient Rome,' which appeared about the same time, and which is supposed to have first been printed in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat." Spalding wrote that a complete version of the parody had not been located and "seems to have been lost to literature, unless this reference to it shall result in its reproduction." But, said Spalding, a friend recalled the opening stanza as follows:

The contemporary reference upon which the poem had been constructed was that of the World's Tour of the Chicago and All-America teams, in 1888-9--a barnstorming, globe-trotting event organized by none other than Spalding himself. The Spalding promotional tour had a dual purpose--both to promote the sport's commercial potential for the Spalding sporting-goods empire; and to "fix the game in the American consciousness as the purest expression of national spirit."[2]

Etruscan overlord Lars Porsena before the gates of Rome, illustration by J.R. Weguelin from 1879 edition of Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome. The horseman to Porsena's right is the crown prince Sextus, whose perfidy began the chain of events which led to the expulsion of the Tarquin rulers and the birth of the Roman Republic

The template to this "other poem" was provided by Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome--beginning specifically with the "Battle of the Lake Regillus," an episode following the Roman revolt against the House of Tarquin, which was the background both to "Horatius" and to the second saga, "Battle of the Lake Regillus." In Roman legend, the Etruscan chieftain Tarquinius Superbus had not given up his hope of reclaiming the Roman throne, leading a confederation of Latin tribes against the infant Roman Republic. Following the heroic defense of the Sublician bridge recounted in Macaulay's "Horatius," this second of Macaulay's "Lays" or ballads of ancient Rome told of the final, futile attempt of the Etruscans to re-establish their rulership over Rome. From the opening lines of Macaulay's ballad:

Ho, lictors, sound the war note;

Triumvirs, clear the way;

The Knights will ride, in all their pride

Along the streets to-day.

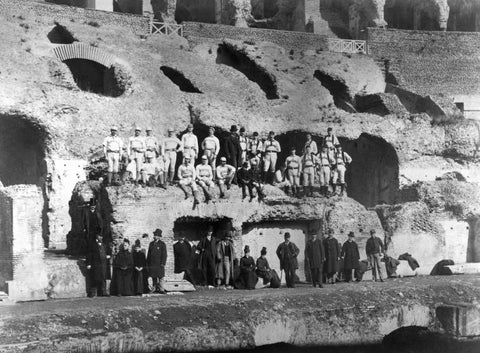

The Chicago and All-America teams posing on the grounds of the Villa Borghese in Rome. The game took place on the 23rd of February, 1889, with Chicago the winners, 3-2. Spalding wrote: Rome was naturally our next point to visit, and there we played in the Villa Borghese, formerly the beautiful home of an Italian prince. The visit to Rome was one of the most enjoyable of the entire tour, so much was there to see of historic interest. King Humbert of Italy honored our game by his presence, and a number of American students at the great Roman College of the Catholic Church were in attendance.

The published date of this parodic ballad could only have followed American press reports of the actual World Tour ball game in Rome on February 23, 1889.

"The knights will ride, in all their pride..." J. R. Weguelin, "Procession of the Knights," wood engraving for Thomas Macaulay's "Battle of the Lake Regillus," in Lays of Ancient Rome (edition dated 1879)

With the clues provided by Spalding, at last the long-sought ballad-- the poem once imagined not just as a counterpart to "Casey" but "...of equal literary merit"-- has been discovered on page 2 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle from Sunday March 17, 1889. One hundred and nine years after Spalding's recollection of the parody, the verses have emerged which in the national press of 1904-05 were put forward as an alternative--and even (though lacking proof) as the original version of Thayer's own ballad!

Here as it was found in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, then later printed in the Philadelphia Times is the ballad entitled "Ansonius at the Bat," the title latinizing the name of Adrian Constantine "Cap" Anson, future Hall-of-Famer (1939) who led the "Chicagos" on Spalding's globe-circling tour.

Adrian Constantine "Cap" Anson 1852-1922

Ansonius at the Bat

Ho, trumpets toot a triumph,

Ho, lictors clear the way,[3]

The great Barbarian ball teams

Will play in Rome this day.

This day the doors and windows

Are hung with garlands all,

From Tiber to the Palatine

To Mars outside the wall.

Unto the great twin ball teams

We'll give a glorious feast;

Swift, swift, the great twin ball teams

Came riding from the East.

They came o'er wild Parthenius,

Tossing in waves of Pine:

O'er Cirrha's dome, o'er Adria's foam,

O'er purple Appenine.

Now is the scene of conflict

With lords and ladies gay,

Now is a flood of Latines

Poured down the Appian way;

The heroes take their places

Midst plaudits, toss the ball,

"Yield not, oh, great Ansonius!"

Loud cry the fathers all.

John "Egyptian" Healy (1866-1899)

John "Egyptian" Healy (1866-1899)

Then Heali, the Egyptian,

He of the Hoosier line,

And Earlus, the barbarian,

With mask and armor shine;

And round about them gathered

Seven heroes strong and bold,

For men played ball for all 'twas worth

In the brave days of old.

William Moffat "Billy" Earle (1867-1946)

"Now by the gods above us

And by our fathers' graves,

Play ball! to-day, Chicagus,

Or be forever slaves!"

Thus spoke the bold Ansonius,

And, speaking, seized his stick.

"One strike." The Tribune cried aloud.

"Come off;" a voice spake from the crowd,

"Mock-a-hi, you make me sick."

Alone stood great Ansonius,

But constant still in mind,

The Egyptian's snakey curves before,

The barbarian brave behind.

"Two strikes." The Tribune shouted,

"Robber, bribed with gold"--

For men kicked hard and men kicked long

In the brave days of old.

Then for a little moment

All people held their breath,

And for a little moment

Reigned silence as of death,

Then in another moment

Brake forth from one and all

A cry as if the Volscians

Were coming o'er the wall.

For with a crash like thunder

Ansonius smote the ball,

It went on high, it journeyed far

And seemed to never fall,

O'er turrets, spires and forum,

O'er many a graceful dome,

And splashed into the Tiber

That rolls by the towers of Rome.

John Montgomery "Monte" Ward (1860-1925)

John Montgomery "Monte" Ward (1860-1925)

And like a horse unbroken

When first he feels the rein,

Ansonius ran the bases,

And ran them not in vain.

Wardius of Manhattan

Seemed stricken to the quick,

He tottered round in dumb surprise

With parted lips and streaming eyes,

While the barbarian Heali cries

"The old man did the trick."

"With weeping and with laughter / Still is the story told, / How well Horatius kept the bridge / In the brave days of old." Final lines of "Horatius," with illustration by J.R. Weguelin from 1879 edition of Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome

Now round him throng the fathers

And maids with laughing eye,

They made a molten image

And set it up on high.

With triumph and with laughter--

Still is the story told

How hard Ansonius slugged the ball

In the brave days of old.

-- As printed in the Philadelphia Times, March 10, 1889, p. 16, with attribution to St. Louis Republic.

"Ansonius at the Bat" was also published in the Buffalo Morning Express on March 12, Brooklyn Daily Eagle on March 17, and in the San Francisco Examiner on March 26, 1889.

Spalding Round-the-World Tour photographed with the Sphinx, February 1889

Spalding Round-the-World Tour photographed with the Sphinx, February 1889

The imagination of the nation had been captured by the Spalding World Tour, and news had traveled rapidly across the Atlantic via undersea telegraph cable. The actual game at Rome between the "great Barbarian ball teams" took place at the Villa Borghese on February 23, 1889. "Ansonius at the Bat" must have been written sometime between that date and early March, when the poem had clearly been shared among U.S. newspapers on the Exchange. Although in fact the Chicagos did depart Rome with the victory, the fireworks were provided not by Captain Anson but by Fred Carroll of the Pittsburgh Alleghenys, a catcher and outfielder for the All-Americas. Carroll hit a two-run dinger onto the piazza terrace of the Villa, earning a standing ovation. But the Chicagos came back to tie the game in the second frame, and won not on the walk-off heroics of "Ansonius" as in the poem, but on a passed ball in the last inning of a seven-inning game.

The Buffalo Evening News published on March 13 a translation of a report on the game at the Villa Borghese by La Tribuna, an Italian newspaper claiming to be the only journal to cover the game. Many people, wrote the Tribuna reporter, had come to the Villa expecting a "ball," and were disappointed to find a game rather than a dance. But the extraordinary athleticism of the players did not disappoint, even though the game itself defied comprehension. In the words of the Tribuna reporter:

It is impossible to explain all of the twists and turns of the ball, the pirouettes which it made around the players, the force with which it was thrown against their adversaries and the dexterity with which it was caught. The ladies explained, "These are not humans; they are demons."

In fact Fred Carroll (1864-1904), shown in this 1887 card at 1st base, provided the home run heroics at the Villa Borghese in Rome -- rather than "Cap" Anson ("Ansonius"). Baseball historian and statistician Bill James wrote that Carroll was the best "young" catcher before Johnny Bench. Carroll still holds an MLB record as an age 24 catcher, with a .970 OPS (on-base plus slugging percentage) for 1889.

The remarkable Chicago shortstop Edward Nagle "Ned" WIlliamson provided vivid accounts of the World Tour to the Cincinnati Enquirer. From Monte Carlo on March 1, Williamson wrote a detailed description of the game at the Villa Borghese, including a box score of the game provided by the correspondent for the Sporting Life. The box score reveals that the pitcher for the All-America team that day was in fact Ed Crane of the New York Giants, rather than "The Egyptian" Healy. Players had to take turns umpiring, and Healy was serving in the rotation that day calling balls and strikes rather than throwing them.

Edward Nagle "Ned" Williamson 1857-1894

The good-natured short-stop-turned-journalist Ned Williamson, who provided such colorful insider accounts of the World Tour, could not have realized in Rome or Monte Carlo that he was in fact nearing the end of his career. Williamson, whose home run record would stand until shattered by Babe Ruth in 1919, would tear his knee ligaments only a week later in a game at the Parc Aristotique in Paris. From this misfortune he would never fully recover, and he would succumb to tuberculosis before the age of 40.

Wherever the anonymous ballad celebrating the game in Rome had first been published, the St. Louis Republic may have garnered the attribution by putting it on the nationwide telegraphic exchange. (In this ephemeral way, "Ansonius at the Bat" also became, like its renowned predecessor, a "ballad of the Republic").

"Battle of Lake Regillus" Tomasso Laureti (1530-1602), fresco in the Capitoline Museums

The many references both to Roman history and to Macaulay's ballads of ancient Rome could be explored at length, but for now it's enough to note that the first three of ten stanzas are drawn almost verbatim from the first three stanzas of Macaulay's "Battle of the Lake Regillus." (Hereafter, references will be to "Regillus" (Battle of the Lake Regillus) or to "Horatius," the first of Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome). Then following those introductory stanzas drawn from "Battle of the Lake Regillus," the rest of "Ansonius at the Bat" is derived entirely from "Horatius," with the title and subtitle, the framework of two contested strikes, the "kicking" of the protesting crowd--and of course the climactic showdown between hurler and striker-- to remind us of "Casey."

Derived from a classical format belonging to one of the 19th century's most famous ballads, "Ansonius at the Bat" would not only appropriate the immediate popularity of the Spalding World Baseball Tour but would also feature the star power of actual players portrayed within the stanzas. Among these were two future Hall-of-Famers, Adrian Constantine "Cap" Anson (1852-1922) whose name figured in the title "Ansonius," and John Montgomery "Monte" Ward --his name latinized as "Wardius." Anson, inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1939, still holds Cubs career records for average (.339), runs (1,712), hits (3,081), singles (2,330), doubles (530) and RBI (1,879). I will not fail to note that Anson's reputation is sadly tarnished by his implacable opposition to African-American players whether on opponents' teams or in professional baseball as a whole. Ward (1860-1925, HOF 1964) whose fame as pitcher and shortstop is attached to that of the New York Giants of his era, not only earned degrees in law and political science from Columbia University, but also formed the first players' union in 1885.

Two lesser-known but nonetheless fascinating players from Spalding's All-America squad found their way into "Ansonius at the Bat." These were John J. Healy, in 1889 employed by the Indianapolis Hoosiers, a tall (6'2") but underweight pitcher nicknamed "The Egyptian" for his birthplace in Cairo, Illinois. Perhaps one of the most curious biographies in all of baseball is that of William Moffat "Billy" Earle (1867-1946), signed by Cincinnati in 1889, who played in the minors and majors from 1884 through 1906. The sturdily-built Earle, whose name was misspelled in Spalding's own recollections of the global tour, overcame a narcotics addiction in the 1890's and continued to play until 1906, as well as to coach for a number of teams including that of Princeton University. Spalding's own list of All America players on the global tour lists "Earl" in right field, but Earle's career position was that of catcher, as referenced in stanza 4 of "Ansonius,"

And Earlus, the barbarian,With mask and armor shine;

But Earle's oft-mentioned attribute was his "mesmerizing," in fact "hypnotic" gaze, documented in his SABR biography by David Nemec:

What is not in any doubt is that [Earle] possessed inordinate hypnotic skills and practiced the “dark” art with great frequency during his days as a ballist. Throughout the 1890s, The Sporting News, Sporting Life, and many papers in major league cities provided documented details of copious incidents — some wandering on for several paragraphs — in which Earle demonstrated his talents for mesmerism in this or that venue.

Mesmerism poster (1885). Billy Earle was a practitioner of the "dark arts"--a mesmerist of "no mean ability" according to his teammates. He was thought by some to have used his powers on umpires to influence their calls.

While the anonymous poem "Ansonius" drew far more direct, less subtle parallels to Macaulay's epics "Horatius" and "Battle of the Lake Regillus" than did Thayer's masterpiece, there is no doubt that it owed as deep a debt to Thayer's "Casey" as it did to Thomas Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome. The title "Ansonius at the Bat," for example, nods to Thayer's predecessor ballad, as does its overall structure and meter, concluding with the poetic trope (first employed by Macaulay, then recycled by Thayer) of "looking back" in the final stanza to the "brave days of old." The dramatic set-up of a first and second strike--and the "kicking" of the protesting crowd--is borrowed directly from "Casey."

The Chicago and All-America teams posed during their tour of the Coliseum. Meanwhile, the Spalding World Tour had "fix(ed) the game in the American consciousness as the purest expression of the national spirit."

The timeliness of the "Ansonius" ballad--based on the appearance of the Spalding tour in the Eternal City and the supposed heroics of the renowned Anson--certainly would have captured the attention of newspaper editors and readers in 1889. Yet even the poem's classical roots would in time have been inadequate to sustain the ballad's place in heart and memory, especially as the contemporary references to actual players of the 1880's--even to the famous "Cap" Anson--would eventually fade. Already by 1911, when Spalding published his compendium of America's National Game, the title as well as the actual opening lines of "Ansonius at the Bat" had been nearly forgotten. What remained was the "Ansonius" parody of lines from "Horatius" -- an evocative classical reference.

Who wrote "Ansonius at the Bat?"

To a young Midwestern journalist laboring on the staff of the Sioux City Tribune, the juxtaposition of the modern American athletic contest and the evocative setting of the Eternal City seemed to demand a literary response.

Frank J. Wilstach 1865-1933

Journalist, theatrical promoter and literary antiquarian Frank Wilstach had since late 1904 been promoting a story published in newspapers nationwide. His account told of a "certain Sunday evening" in the mid-1880's (Wilstach was never very clear on the exact date), as two young journalists on the staff of the Sioux City Tribune were whiling away their time. Young Frank Wilstach, himself the son of a literary family from Lafayette, Indiana, told several versions of the following story:

Will Valentine, a young Irishman, came up from the Kansas City Star to the Sioux City (Iowa) Tribune in 1885 to be city editor. He was constantly writing verse. On the back page of the Tribune I was at that time conducting a column which, shamefacedly I may say, was supposed to be like Eugene Field's "Sharps and Flats" in the Chicago Record. It was bad, but Valentine every once in a while would hand me a bit of verse which I would run, he signing it "February 14" being St. Valentine's day, as 'twere.

Valentine and I were roommates. My brother Walter sent me a set of Macaulay's works and one Sunday evening, reading "Horatius at the Bridge," I said to Valentine that here was a good opportunity to parody "Horatius" by a poem about a Mick at the Bat. We were then baseball crazy. Valentine read the Macaulay poem and went ahead and wrote a piece he called "Casey at the Bat."

It is rather curious (Wilstach went on) that all the claimants for this poem have been seemingly unaware that "Casey at the Bat" is a parody on "Horatius at the Bridge," with the same meter and the end of each stanza very nearly the same.

I left Sioux City in 1887, wrote Wilstach, and never heard of Valentine or thought anything of his poem until one night I met him on lower Broadway in 1898. I was then press agent at the Broadway Theatre and Valentine was employed on the New York World. .....

John Healy ("Heali" in the poem was a more exotic spelling, befitting the Roman setting) was pitching for the All-Americas, It is true that Healy "The Egyptian" at 6' 2", weighing 158 pounds, certainly would have provided a "snaky" impression on the mound, though he specialized in the fastball, not the curve. This fact that Healy's nickname was known to the author of "Ansonius at the Bat" certainly lends credence to Wilstach's story that the two young journalists that Sunday afternoon were "baseball crazy." Further evidence of the baseball savvy of the author of "Ansonius" was his reference to the catcher's "mask and armor" worn by "Earlus" -- the "barbarian brave" posted behind "Ansonius," the "Chicagus" striker, as he confronted "The Egyptian" on the mound.

Lays of Ancient Rome (1842) by British parliamentarian and historian Thomas Macaulay, was a best-seller both in Britain and America.

That the two young newsmen were confined to their rented room on a Sunday afternoon (as in other variants of Wilstach's recollection) reading epic poems, provides another hint that the remembered episode took place in deep mid-winter. And lending additional credence to Wilstach's persistent memory of the occasion, the author of "Ansonius at the Bat" must have had the actual text of "Lake Regillus" and "Horatius" close at hand, so closely do the verses reflect--in many cases verbatim--Macaulay's original lines.

Wilstach had an encyclopedic memory for metaphors and similes, but his recall of the calendar was sketchy. We know that whether or not Wilstach was working for the Broadway Theatre in 1898, as he claimed, he could not have met Will Valentine on Broadway that year. Valentine had perished of mastoiditis while managing the Octagon Hotel on Oyster Bay. He had been laid to rest by his journalist colleagues in July 1897.

Could the parody of Macaulay's "Battle of the Lake Regillus" have been penned by the classically-educated Irishman Will Valentine, inspired by the Spalding World Tour to fill a back page column of the Sioux City Tribune? Was Wilstach's memory of the origin of "Casey" based both on Macaulay's "Horatius" and on "The Battle of Lake Regillus?" Spalding's hint of the existence of a baseball-themed parody of a Thomas Macaulay poem suggested that a baseball version of Macaulay's battle-epic was not merely an elaborate fiction perpetrated by Frank Wilstach and Will Valentine. The evidence now suggests a real baseball poem in epic mode--not "Casey," but an 1889 comic parody of Macaulay's verses--a "re-imagined Casey"-- not only existed, but was (for a time) put forward as the counterfeit "Casey." After all, for the average newspaper reader of Thayer's day, the date of the real "Casey's" emergence in the San Francisco Examiner in June 1888 would not have appeared significantly anterior to the appearance of "Ansonius at the Bat" in March of 1889.

The evidence is circumstantial, but compelling, that the poem claimed by Frank Wilstach as the original "Casey at the Bat," was not only a parody of Thayer's original, but also aspired to be an improvement on it. Will Valentine, with his colleague Frank Wilstach at his elbow, no doubt thought that a more explicit mimicry of Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome would attract a broader readership than had the version penned by the unknown "Phin"-- as would the comic references to Anson and other heroic players of the day! And would not the glories of Rome, the Eternal City, outshine the dismal byways and humble hearths of "Mudville?"

And in this first of hundreds of "Casey"-based parodies to follow, Will Valentine set the precedent which would diminish so many of those successor ballads. He, like most Americans from that day to this, so desperately wanted Casey (or his "Ansonius") to "slug the ball" out of the park that he extracted all the ennobling catharsis from the legend! This poetic twist was true to the Roman version of the "Horatius" legend popularized by Macaulay--true because the Romans, above all else, abhorred failure and would do anything to avoid defeat. But "Phinney" Thayer, drawing on the wisdom of the ancients from his classical education, knew that the muse Melpomene, the originator and protector of Greek tragedy, would convey through "Casey's" ballad a far more powerful and lasting truth.

DeWolf Hopper retained Frank Wilstach from 1896 though 1900 as press agent and promoter. Frank was often credited with the success of Hopper's successful production of "El Capitan" in London beginning in the fall of 1899.

DeWolf Hopper retained Frank Wilstach from 1896 though 1900 as press agent and promoter. Frank was often credited with the success of Hopper's successful production of "El Capitan" in London beginning in the fall of 1899.

Frank Wilstach's motives for pushing an alternative authorship for "Casey" are murky. By the time Frank began promoting his story of the Sunday afternoon discovery of Macaulay's ballads of ancient Rome, Will Valentine had been dead for seven years. We do know, however, that from 1896 until perhaps mid-1900, Wilstach had served as DeWolf Hopper's press agent and promoter--a close relationship that appeared to end abruptly. The true story of Frank's attempt to debunk Thayer's authorship probably had more to do with backstage grievances and intrigue within the theater world, particularly as Hopper's crowd-pleasing recitations of "Casey at the Bat" had become wildly popular from coast to coast--while "Ansonius,"its classical template and references to the great Cap Anson and Monte Ward notwithstanding--had by the 20th century faded into the crinkled oblivion where most of the newspaper humor of that era would repose.

As for Ernest Thayer's response to Wilstach's alternative account of Casey's genesis, it was wrathful and immediate--and in the long term, with the help of Harvard friend and classmate "Genie" Lent, and the Pinkerton agency--effective and perhaps even vengeful. That's a story for another post. But Thayer's vigorous defense of his authorship in 1905 should forever lay to rest the notion (purveyed in the 20th century) that "Casey's" author cared little for his most famous creation.

Yet its way the ballad of "Ansonius at the Bat" would eventually help to authenticate the classical template chosen by Thayer for his "Casey." And it would remain the key evidence of the reputedly brilliant but short-lived career of the young Irish writer, singer, and baseball enthusiast Will Valentine. More about Valentine in a later blog--but next we'll turn to the discovery of yet more 19th-century baseball poetry in classical mode!

Finally, back to the text of the "Ansonius" ballad: can anyone explain the derisive cry of "Mock-a-hi" in stanza five? I have assumed this was an editorial hiccup of some kind, but it may represent a baseball trope of that era--or comic variation of same--which has faded from living memory. Any help? @thorn_john ? @Ed_Achorn ? @MitchNathanson ? @baseballminutia ? @nut_history ? @PulpEphemera ? @ClaytonTrutor ? @PaineProffitt ? @BaseballChaz ?

#CaseyattheBat #BalladoftheRepublic

[1] Spalding, Albert G. America's National Game: Historic Facts Concerning the Beginning, Evolution, Development and Popularity of Baseball. New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1911. (See Chapter 32: POETIC LITERATURE OF BASE BALL—INTERESTING STORY OF "CASEY AT THE BAT"—ITS AUTHOR—DE WOLF HOPPER'S PART IN MAKING THE POEM A CLASSIC—OTHER POEMS)

[2] Cover promotion for Mark Lamster, Spalding's World Tour: The Epic Adventure That Took Baseball Around The Globe--and Made It America's Game (New York: Public Affairs / Perseus Books Group), 2006.

[3] Stanza One matches closely the first stanza of The Battle of the Lake Regillus, by Macaulay, which begins "Ho, trumpets, sound a war-note! Ho, lictors, clear the way! / The Knights will ride, in all their pride, Along the streets to-day." (Hereafter, references will be to "Regillus" (The Battle of the Lake Regillus) or to "Horatius," the first of Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome and the poem referenced most frequently by the author of "Ansonius at the Bat."

John "Egyptian" Healy (1866-1899)

John "Egyptian" Healy (1866-1899) John Montgomery "Monte" Ward (1860-1925)

John Montgomery "Monte" Ward (1860-1925) Spalding Round-the-World Tour photographed with the Sphinx, February 1889

Spalding Round-the-World Tour photographed with the Sphinx, February 1889 Mesmerism poster (1885). Billy Earle was a practitioner of the "dark arts"--a mesmerist of "no mean ability" according to his teammates. He was thought by some to have used his powers on umpires to influence their calls.

Mesmerism poster (1885). Billy Earle was a practitioner of the "dark arts"--a mesmerist of "no mean ability" according to his teammates. He was thought by some to have used his powers on umpires to influence their calls. DeWolf Hopper retained Frank Wilstach from 1896 though 1900 as press agent and promoter. Frank was often credited with the success of Hopper's successful production of "El Capitan" in London beginning in the fall of 1899.

DeWolf Hopper retained Frank Wilstach from 1896 though 1900 as press agent and promoter. Frank was often credited with the success of Hopper's successful production of "El Capitan" in London beginning in the fall of 1899.