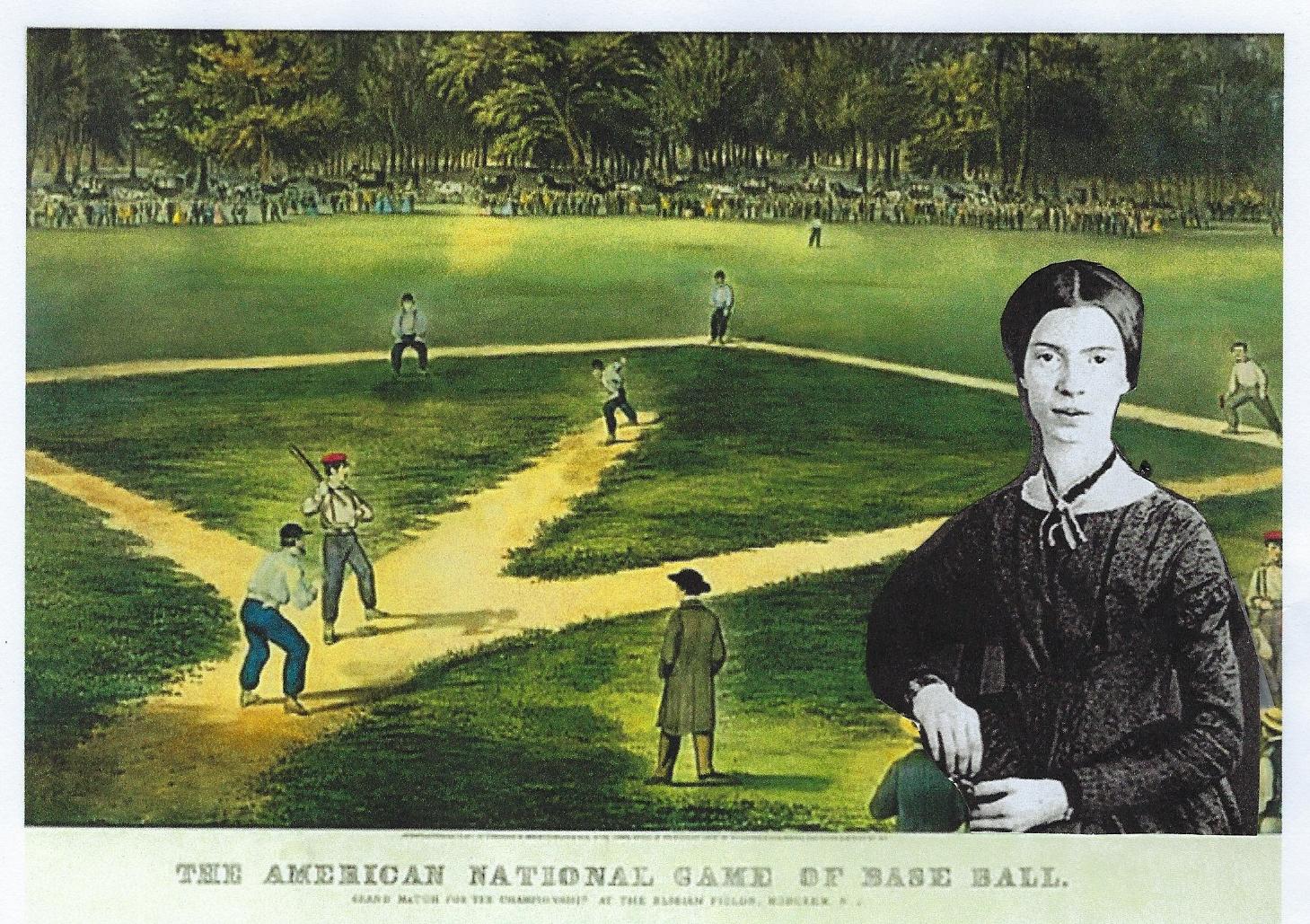

Emily Dickinson in the Elysian Fields

Poet and translator A. M. Juster has referred to “Casey at the Bat,” as "perhaps the most enduring poem of American popular culture." (Its only rival for that distinction, says Juster, is Clement Moore’s 1823 poem, “Twas the Night Before Christmas," or, as it was originally titled, "A Visit from St. Nicholas.") While there are other contenders for preeminence among these and 19th-century American poems, there is no contention regarding the current popularity of 19th-century American poets. The best loved 19th-century American poet--at least based on recent Google search protocols--is Emily Dickinson. Her poem beginning "If I can stop one heart from breaking..." renders over 19 million Google search results in the blink of an eye.

In re-reading a number of Emily's poems on the occasion of her birthday, I realize there is a playfulness to her poetry--even regarding serious subjects-- which lovers of sport can recognize and celebrate. So on the occasion of her 190th birthday--and again on her 191st--Caseyatthe.blog pays tribute to the rare genius of Emily Dickinson by imagining a version of "Casey at the Bat" as she might have written it from the watchful isolation of her room at "The Homestead" in Amherst:

Betimes the score stood four to two

Betimes the score stood four to two,

So fast the game had sped--

The little feathered thing of hope

From every breast had fled.

I witnessed all that would transpire

From the window where I lay--

As from my curtained aerie

I watched the lads at play.

Two times the hurler spun a strike--

Twice the batsman did abstain--

Though loud the crowd implored the Judge,

Their supplications fell in vain.

At edge of dusk the striker poised

In a certain slant of light--

In ecclesial awe the silent crowd

Beheld the orb in flight--

He swung! But did not smite the ball--

My soul was overwrought;

My meager consolation such

As ancient poets taught.

I saw the batsman drop his bat

As dusk gave way to night--

As Angels grieve at human deeds

From their celestial height.

--With gratitude to Emily Dickinson

from Richard Collins Davis

© All rights reserved Caseyatthe.blog April 3, 2020

In ancient times, bards and balladeers called often upon the Muses. As Michael Grant and John Hazel wrote in their Who's Who in Classical Mythology,

The importance of the Muses arises from their popularity with poets, who attributed to them their inspiration and liked to invoke their aid. Their name (akin to the Latin mens and the English mind) denotes 'memory' or 'a reminder,' since in the earliest times poets, having no books to read from, relied on their memories.

"Homer Singing His Iliad at the Gates of Athens," Guillaume Lethiere (1760-1832)

It is whimsy, of course, to have speculated (see "Song of Our Game,") on which of the Muses visited Ernest Lawrence Thayer during the spring of 1888 at his family home on Chatham Street in Worcester, Massachusetts. At first I assumed that Thayer's inspiration could be attributed to none other than Calliope, the Muse of Epic Poetry, until I saw the enormous statue of Melpomene, Muse of Tragedy, which resides in the Hermitage museum in St. Petersburg. Melpomene's hand rests upon an enormous bat (or club) which suggests not only the power of tragedy but also the potency of the wisdom which her lessons generally convey.

Melpomene, Muse of Tragedy, in the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. The Muses were the daughters of Zeus and the Titaness Mnemosyne --whose name means "memory," and from which we obtain our word "mnemonic."

Alas, my humble doorstep has never been darkened by either the implacable Melpomene or the silver-throated Calliope. I am visited from time to time only by the disheveled, irreverent Parodia--red-haired step-sister of her formidable sister-deities. Parodia--while never mentioned in the roll-call of the nine classical Muses--nevertheless retains a mischievous charm of her own, which in my pandemic-imposed isolation I am powerless to resist.

So it may be fate or happenstance that when the hour came round for the great American Baseball Ballad to be introduced to the American public, that the sister-Muses had arrived too late in Amherst. By the spring of 1888, when Ernest Thayer was called to take up his pen to bring "Casey" to life, the brilliant Dickinson had "scarce adjusted in the tomb," as she herself had written. She had expired on May 15, 1886.

We can fairly speculate that the popular game of baseball would not have escaped Emily's keen observation, nor would the open windows of Emily's room within the Homestead have been so high above the playing fields of Amherst that the cheers and chants of the afternoon "base ball" game would have been muted or ignored.

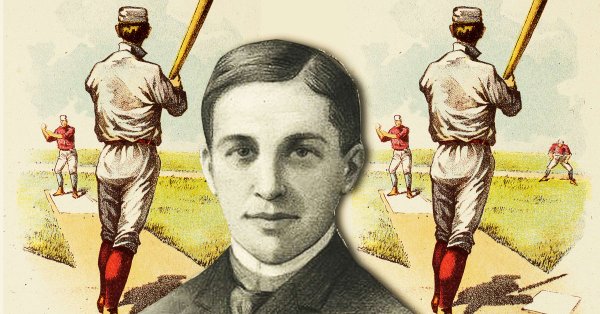

Gilbert "Gib" Dickinson, 1875-1883

Too, there was the Dickinson family's fascination with the mischievous exploits of the brilliant and spirited Gilbert "Gib," Emily's nephew, son of her brother Austin. Not only Emily and her family but, if the reports can be believed, nearly the whole population of Amherst was captivated by the boy. "Base ball" would certainly have been one of Gib's pastimes. One must imagine young Gib as both the impresario and star of games played on the adjoining grounds of The Evergreens (Emily's brother's home) and the mansion where Emily lived. "The Playthings of the Dervish were not so wild as his..." wrote Emily. Though Gib's promising young life was cut short by typhoid, his influence on the family, and on Aunt Emily in particular, had been profound.

Emily's verse was spare, each poem unique and gemlike; Thayer's imagery borrowed from a robust repertoire of epic poetry dating to Homeric times. So if Emily had ever been visited by the Muses who inspired "Casey," perhaps her contribution to the literature of baseball would have emerged somewhat along the lines of "Betimes the score stood four to two."

Emily Dickinson illustration by Johanna Goodman for Smithsonian Magazine, April 2017

And see the timely essay on the poetic virtues of isolation, as practiced by Emily Dickinson, written by Erika Scheurer, Associate Professor of English at the University of St. Thomas and published in the Minneapolis Star-Tribune.

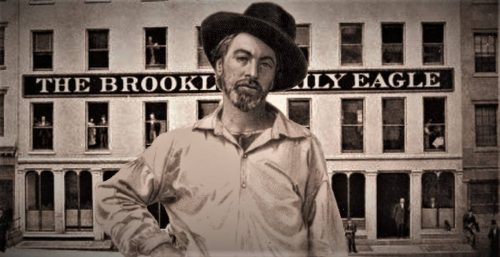

How might Walt Whitman have envisioned the classic baseball saga? See Song of Our Game: The Ballad of Casey as Imagined by Walt Whitman (February 22, 2020). And to round out the pantheon of 19th century American poets, how might Edgar Allan Poe have told the story of Casey? See "Casey in Ulalysium" elsewhere in these pages. In the 20th century, aspiring pitcher Robert Frost might even have taken his fateful swing: see "Casey Stops By the Ball Park on a Snowy Evening."

#CaseyattheBat #EmilyDickinson #BalladoftheRepublic @thorn_john @amjuster @ClaytonTrutor @PaineProffitt #NationalPoetryMonth @klgiven @worcestermag @DickinsonMuseum @UofStThomasMN @Ed_Achorn @DrPaulRSem @poetech3 @k72ndst @TheLambsInc

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.