Can't Win For Losing: The Drama of the Mighty Casey

Player photo: Tim Wiles, formerly of the Baseball Hall of Fame, in costume as The Mighty Casey.

The magical season of the year as experienced by fans of Ernest Thayer's "Casey at the Bat" is the period between June 3 and August 14. For several notable reasons. To begin with: June 3 is the date in 1888 in which the ballad of "Casey at the Bat" was published in the San Francisco Examiner's Sunday edition under Ernest Lawrence Thayer's byline, "Phin."

And August 14 (also 1888) is the date on which "Casey" made his debut on Broadway, thanks ultimately to ascendant star DeWolf Hopper.

Escaping the crinkled oblivion to which most newspaper verse of that era was destined, the ballad of "Casey" made a dramatic transcontinental leap as the Sporting Times editor picked it up, dropped the first five stanzas with their references to California baseball and its landscape, and substituted the name of "Kelly" to evoke the Boston Beaneaters' Mike "King" Kelly -- one of the most popular players in the country at that time. (Oh yes, "Boston" also was substituted for the lowly "Mudville)." In this truncated, corrupted format the ballad first debuted on the East Coast.

"Colonel" John A. McCaull -- the father of American comic opera

Fortunately, the original Examiner version had been clipped by author Archibald Gunter on a visit to San Francisco and passed along to "Colonel" John McCaull, manager of the opera company bearing his name. Seeing the potential for a dramatic reading of the poem for "baseball night" at Wallack's Theatre--featuring the hometown Giants and the visiting Chicago White Sox in attendance--McCaull passed along the 13-stanza ballad to his star, DeWolf Hopper, who quickly committed the verses to memory and practiced his dramatic flourishes.

Caseyatthe.blog is pleased to be able to bring our readers the story of The Mighty Casey as dramatized by (and with the permission of) the talented King Kaufman, senior audio producer for the San Francisco Chronicle and author of the intriguing podcast, Can't Win 4 Losing. Kaufman (see his bio below) has a clear connection to Ernest Thayer: both Kaufman and Thayer began their careers as journalists at the San Francisco Examiner.

I'll include a few more comments after you've listened to the podcast but without further distraction, here is the link to

Episode 1: The Mighty Casey — Casey at the Bat, striking out for over a century

"It appeared on Page 4 of the San Francisco Examiner one day in 1888, and yet, somehow, Casey at the Bat survived to become one of the few 19th century American poems most Americans have even heard of. CW4L host King Kaufman goes in search of the story behind the remarkable staying power of a poem about a guy who (spoiler alert) struck out, written by a guy who wanted nothing to do with it after it was published...."

People featured in the story:

Joanne Hulbert is an emergency-room nurse and baseball poetry researcher, and the town historian of Holliston, Mass., which, along with Stockton, Calif., lays claim to being the “real” Mudville. Poet Ernest Thayer was from nearby Worcester. She wrote about DeWolf Hopper at The National Pastime Museum.

Hal Bush (1956-2021)

Hal Bush was a beloved professor of English at Saint Louis University and a writer of criticism, biography, history and fiction. His most recent book is the novel The Hemingway Files. His untimely death from a fall is mourned in this memorial from Saint Louis University .

The recital of Casey at the Bat is by Neil Rogers.

Historical figures

DeWolf Hopper (1858-1935) was a musical-theater star who made Casey at the Bat famous by performing it with members of the New York Giants and Chicago White Stockings in the audience in 1888, causing a sensation. It became his signature piece, and he claimed to have performed it more than 10,000 times. His 1927 autobiography, quoted in the episode, was Once a Clown, Always a Clown. Voice impersonation: Jonathan Luhmann. Hopper’s real voice is also heard.

Ernest Thayer (1863-1940) was the author of Casey at the Bat. The Marky Mark of poetry, a one-hit wonder. A brilliant student at Harvard and the editor of the Harvard Lampoon, he was invited to San Francisco to write humorous pieces and verse for the Examiner by his classmate, William Randolph Hearst. Casey at the Bat was his last submission. He’d already gone back to Massachusetts to run the family woolen-mill business and wanted little to do with his famous poem. Voice impersonation: Joe Goffeney.

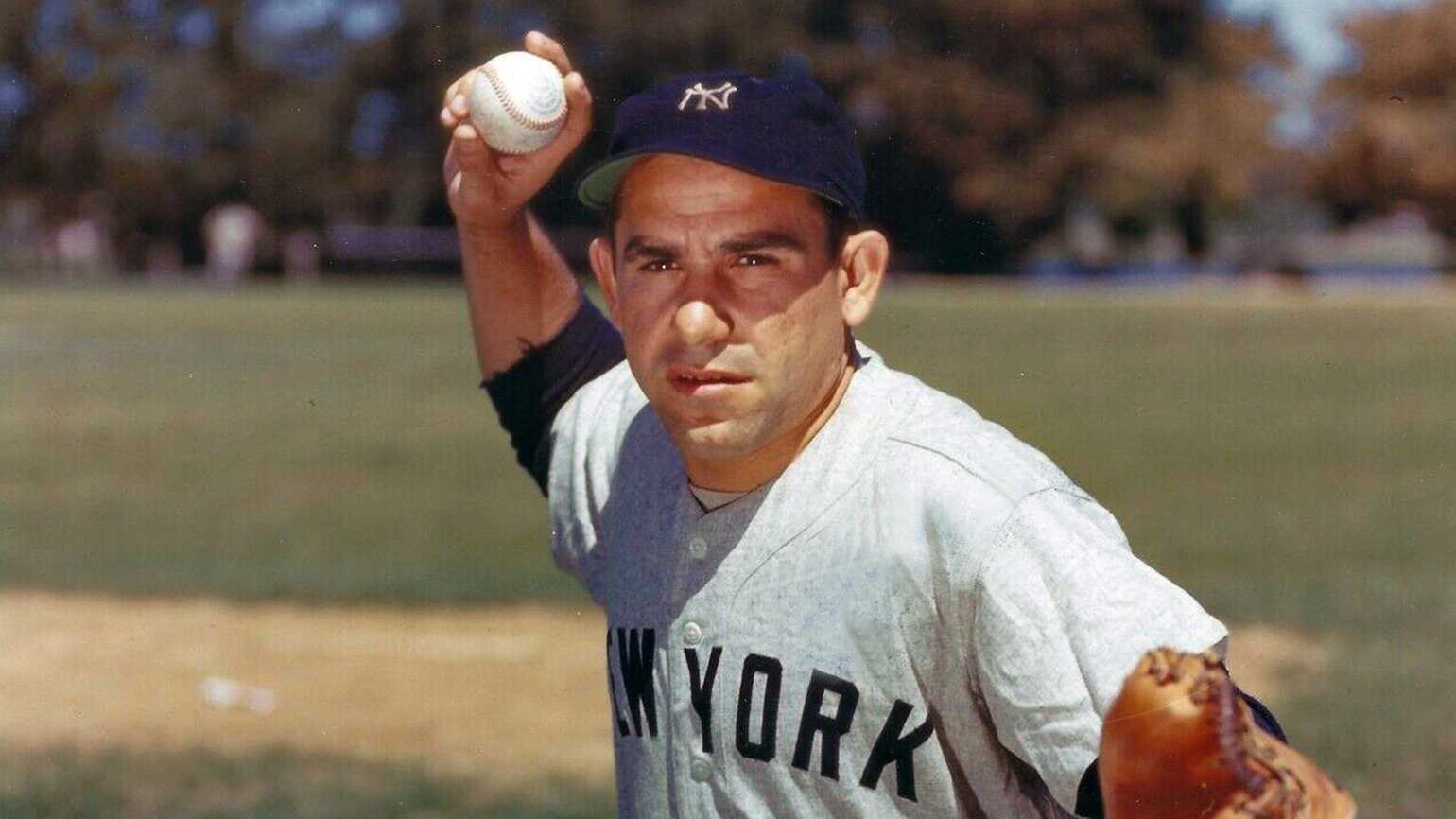

Mike “King” Kelly (1857-1894) was baseball’s first superstar. He played every position but was mostly an outfielder and catcher. He was a batting champion and great base-stealer. Kelly was the subject of “Slide, Kelly, Slide,” the first pop song to become a hit record, and his (ghostwritten) autobiography was the first by a baseball player. He was convinced Casey at the Bat was about him, and he performed it — by most accounts very badly — as Kelly at the Bat. He died suddenly of pneumonia at the age of 36 and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1945. He’s shown here in his Boston Beaneaters uniform, possibly in 1888, the year Casey at the Bat was published.

Music

Opening Theme: “Big Swing Band” by Audionautix. (CC by 3.0)

Closing Theme: “Can’t Win For Losing” by Johnny Rawls, courtesy of Deep South Soul Records. Visit Johnny Rawls’ website and Facebook page.

His latest album is called Waiting For the Train.

The old-timey piano music throughout this episode is from old player-piano or pianola rolls. The music at the very beginning is “Old-Fashioned Auto Piano” by Razzvio. Similar music elsewhere is from a medley called “Follies” by Daveincamas. The artists here did the recording and manipulated the pianolas. The actual musicianship happened 100 or more years ago. The sad piano music is “Movie Piano Theme” by EK Velika. All of these songs are from FreeSound.org and are used under the CC BY 3.0 Creative Commons license.

Concluding Comments

Now that you've heard Kaufman's wonderful narrative of the origins of "The Mighty Casey," Caseyatthe.blog will leave you with just a few observations:

- Readers of this blog will learn that Caseyatthe.blog is skeptical of the association of Mike "King" Kelly with the legendary "Casey," whose fictional fame has rather eclipsed the notoriety of any particular (actual) player of the 1880's. As for the inspiration for the ballad itself, Thayer often cited the heroic achievements of his classmate and friend Samuel Ellsworth Winslow, captain of the immortal Harvard nine of 1885. And deeper examination of the ballad discovers a template in an ancient legend of the Roman republic, retold in 1842 by Thomas Macaulay's "Horatius." Nevertheless Caseyatthe.blog encourages enthusiasts of the "King Kelly" version of "Casey" to continue their research -- one never knows what may turn up!

- Kaufman rightly raises the question, other than "Casey at the Bat," do we really know or remember any other 19th century American poems? It turns out that there are a few 19th-century verses which can claim the attention of 21st-century audiences-- among them, "The Raven," by Edgar Allan Poe; "If I Could Stop One Heart from Breaking," by Emily Dickinson; and of course "A Visit from St. Nicholas," better known by its first line, "'Twas the night before Christmas..." by Clement Clarke Moore. Yet the character of The Mighty Casey has claimed a particular status in American folklore rivaling that of John Henry, Paul Bunyan, Pecos Bill, or even man/myth hybrids such as Davy Crockett and Johnny Appleseed.

- Kaufman features the voice of the now-lamented professor Hal Bush, who reminds us how well-written "Casey at the Bat" has demonstrated itself to be. Thayer's elevated style raises the Mudville strike-out to the status of a classical tragedy.

- Note well the cameos of wisdom from Major League Baseball's official historian, John Thorn, who observes that the poem's appeal derives from our sense that Casey's fate could not have been otherwise: "We don't want vindication," says Thorn, and particularly "we don't like pomposity" -- as we respond to the drama of hubris which retains the inexorable power to drop a minor-league slugger as low as an Achilles of ancient lore.

- I salute Kaufman for his painstaking attribution of credit to all the participants in his narrative, including musician Johnny Rawls. He sets an example for all of us whose work rests on the shoulders of all those who have preceded and educated us!

Cover image:

Calvert Lithographing Co, C. C. (ca. 1895) Full Sheet Base Ball Poster No. 281. United States, ca. 1895. May 11. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2008677269/. (And thanks to John Thorn for posting the image and sending me the reference).

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.