On Heroism, Hubris, and Humility

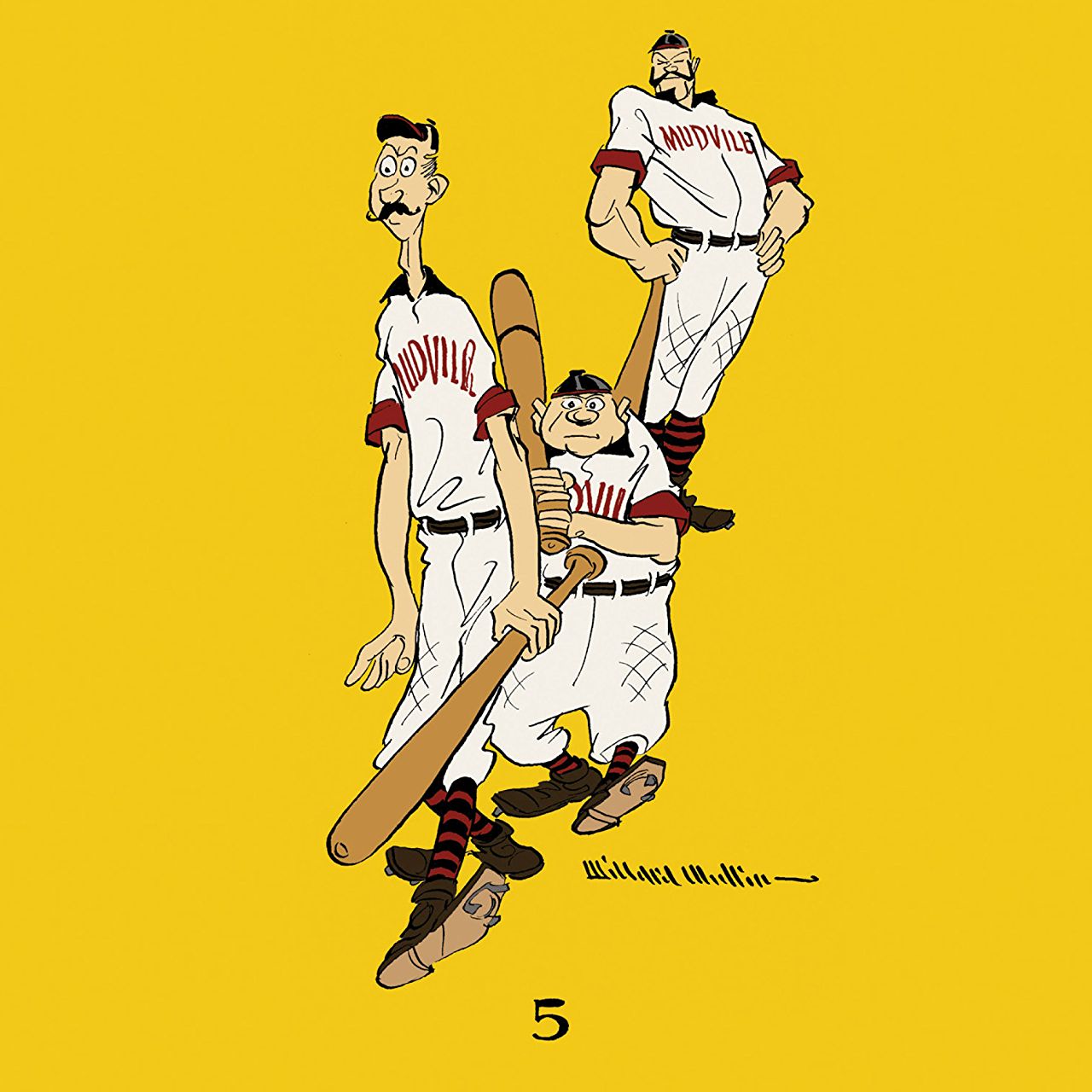

I love the way that "Casey at the Bat" has threaded itself into American consciousness, continuing proof of the ballad's relevance to an understanding of the place of baseball within American culture. Although we explore elsewhere in Caseyatthe.blog the growing popularity of baseball within other countries, as well as the universality of "Casey's" themes, there is no doubt that Americans have granted "Casey" a favored status within their national folklore. And also that Americans, looking back into Thayer's 1888 ballad as through a glass, darkly, perceive a variety of lessons that may tell us more about ourselves as Americans than about the familiar slugger standing "at the bat" in a long-ago game at the Mudville ballpark.

These thoughts were prompted by Sports Editor Dusty Metzgar's recent "Odds and Ends" column in the Weston (West Virginia) Democrat -- a venerable local journal published since 1868. Metzgar muses on metaphors rooted in baseball lingo, such as "hitting a home run," "striking out," "touching base," and so forth. "It blows my mind," writes Metzgar, "that baseball has given our culture so many movies, songs, and even poems, the most famous of which has to be "Casey at the Bat," by Ernest Lawrence {Thayer}. I memorized it in seventh grade and I still know it, and I've always loved its message of 'humble yourself or the game will humble you...'"

Baker Mayfield plants the University of Oklahoma flag at the Buckeye midfield--an act for which he later apologized (Sept 9, 2017)

The idea of humility as a quality to be emulated by athletes, or by modern heroes in general, is actually a relatively recent phenomenon. At the highest levels of today's competition, humility is a virtue perhaps more admired than actually practiced. I clearly recall the Rose Bowl college football playoff game on New Year's Day, 2018, pitting the number-two ranked Oklahoma Sooners and their exuberant quarterback Baker Mayfield against the number-three ranked Georgia Bulldogs. For Buckeyes like me the game had a particular interest, because earlier that season Oklahoma had prevailed at Ohio Stadium in Columbus--concluding with Mayfield's seizing an Oklahoma flag from the cheerleaders and planting it in the middle of the Ohio State "block O" at the 50-yard line. Buckeyes were justifiably outraged and many (like me, I confess) were hoping to see a different outcome for Mayfield in the Rose Bowl.

It looked as if the Big 12 champions might prevail when they led 17-10 at halftime. But the third quarter established Georgia's steady superiority, especially on defense, which held Oklahoma scoreless. As the clock wound down in the final quarter, with Georgia ahead 54-48, Mayfield--on the Sooner sidelines--was visibly distraught. As the Sooners departed the field in defeat, Georgia players shouted after Mayfield--whether as consolation or simple counsel--"Humble yourself, man, humble yourself." Indeed it was wise advice from the Georgia players. Only a week later, the Bulldogs would themselves tread the path of humility after a close contest in overtime led to defeat, 23-26, against Alabama in the 2018 College Football Championship.

Casey, of Thayer's ballad, demonstrated classical heroic virtues--but humility was not one of those.

So the lesson in humility Dusty Metzgar took from the ballad of The Mighty Casey was a valid one. But humility was not Casey's strong suit. Casey's fatal flaw was that of hubris, a pride in one's own abilities or position so excessive that it left no room for humility. In that last moment (in Stanza 12) before the third pitch is thrown, it is possible that Casey experienced anagnorisis--the startling moment of self-discovery characteristic experienced by the protagonists of Greek drama--specifically of the drama at which Greek playwrights excelled-- tragedy.

Publius Horatius Cocles leads the Romans in battle against the Etruscans, by Tommaso Minardi (1787-1871)

Publius Horatius Cocles leads the Romans in battle against the Etruscans, by Tommaso Minardi (1787-1871)

Such heroic deeds as those drawn upon by Thayer in his immortal ballad were recounted by Livy (patronized by the Emperor Augustus) and other Roman historians as examples for true Romans to follow, illustrating the placing of state above the interests of the individual.[1] From such stirring myths, writes Carl J. Richard, Roman youth were taught "courage, discipline, persistence, patience, self-restraint, hard work, endurance, honesty, piety, dignity, and manliness. The last of these qualities was virtus, whence comes the English word 'virtue'"[2] "Manly virtuosity," a better translation of the Latin virtus, is epitomized by Horatius at the bridge, defiantly confronting the Tuscan army at the gates of Rome. It was understood by all Romans that Horatius expected no material reward for his bravery, rather, he "could imagine no nobler death than one in defense of Rome."

Emerson's Heroism

One last point about heroism as it was understood in mid-19th century America, which is to say, by the generation which would fight the Civil War.

Ralph Waldo Emerson 1803-1882

Emerson's definitive essay "On Heroism" was first published in 1841. Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome, published in America in 1842, resonated with the classical virtues of the Emersonian hero: his self-confidence; contentment with "the perception that virtue is enough;" asceticism in character ("it does not need plenty, and can very well abide its loss"); satisfaction with the constraints of place and time ; " persistence; self-reliance, especially with regard to the opinions of others; yet unselfconsciously given to the good humor, even the towel-snapping hilarity that most struck Emerson's fancy as he described "the heroic class."

More dangerously, perhaps, and in this aspect of his thinking most resembling the ancient Greeks, Emerson suggested that actual demonstrations of heroism transcended all criticism. In spite of their inherent extremism and potential unholiness, there was something about heroic acts that in Emerson's opinion demanded to be revered. Like Aristototle's Magnanimous Man, as the philosopher depicts him in the Nichomachean Ethics, Emerson's hero is individualistic, self-sufficient and proud-- like the heroes of antiquity. But in fact, as Father McNamee observes in his Honor and the Epic Hero,[3] the self-centeredness of Aristotle's great-souled man--his insistence upon the full measure of honor and acclaim which is his due--"betrays not only the bad side of Aristotle's ethics but the bad side of the whole Greek humanistic ideal--an exaggerated individualism and selfishness."

Tod Lindberg, in his perceptive study, The Heroic Heart , has pointed out that "if heroism is confined to its classical form, there are no more heroes."[4] This was precisely the point of Thayer's plaintive lament in his 1885 Class Day Oration: "There is no place in Cambridge for the young man of heroic intentions." Scottish philosopher, historian, and satirist Thomas Carlyle's attempt, in the mid-nineteenth century, to revive the practice of "Hero-worship" ( a word he is considered to have coined), was losing traction even as it was propounded: modern men and women were far less likely than their ancestors to bow down to anyone, regardless of status or achievements. Yet we know that true heroes still exist, though in their present-day incarnation they uniformly insist on NOT being called "heroic:" the firemen, cops, and ordinary human beings who claim "I was just doing what I was trained to do," or "I did what anyone else would do under the circumstances." So speak the modern heroes, whom Lindberg terms the "saving heroes," as opposed to the "slaying heroes" of former times. In Lindberg's reexamination of the heroic, the modern meaning of greatness is service to others.[5]

The Rage of Achilles: "Hector's death and Achilles triumphant protected by Mars," by Antonio Galliano (1785-1824)

Even in the golden age of Athens, it was clear that the ego-driven individualism of the Homeric warrior-hero would have to be tamed. To Achilles, Hector, Ajax and the other characters in the Iliad, the idea of fighting for one's "fatherland" as expressed by Hector, rang a false note: the point of warfare was to kill, to enhance one's personal honor, and to acquire the material possessions--trophies, slaves, and cities--emblematic of both honor and physical prowess. The truth of warfare in the world of Odysseus, as M. I. Finley taught, was that " a notion of social obligation is fundamentally non-heroic."[6] But as Greek city-states tamed their heroes, harnessing ego-driven prowess for the benefit of the community, the competitive energy of the warrior was translated into contests--both literary and athletic.

Samuel Ellsworth Winslow 1862-1940

Samuel Ellsworth Winslow 1862-1940

From the post-Civil War generation of Winslow, Thayer, Santayana and their classmates a different kind of heroism would be required. And that is a topic that we'll come back to in later blogs! In the meantime, see our article "Sam Winslow" as an example of post-Civil War heroism modeled by a truly exceptional young man.

[1] Richard Holland, Augustus: Godfather of Europe (Stroud, Gloustershire: The History Press, 2009), p.276.

[2] Carl J. Richard, Greeks and Romans Bearing Gifts: How the Ancients Inspired the Founding Fathers (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2008), p. 102.

[3] Maurice B. McNamee, S.J., Honor and the Epic Hero (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc., 1960), pp. 1-5.

[4] Tod Lindberg, The Heroic Heart: Greatness Ancient and Modern (New York: Encounter Books, 2015), p. 143.

[5] Ibid., p. 172.

[6] "For that step the world of Odysseus was of course unprepared," wrote Professor M. I. Finley (1912-1986) in The World of Odysseus. "It was also unprepared to socialize the contest, so to speak. Diomedes sought victory in the chariot race, as on the battlefield, for himself alone, for the honour of his name and in a measure for the glory of his kin and companions. Later, when the community principle gained mastery, the polis shared in the glory, and in turn it arranged for victory songs and even public statues to commemorate the honour it, the city had gained through one of its athletic sons. And with the dilution of the almost pure egoism of heroic honour with civic pride went still another change for which the Homeric world was unprepared: the olive wreath and the laurel took the place of gold and copper and captive women as the victor's prize."

Cover Photo: Opening Day, 2018, of the Lewis Baseball Association, Lewis County, West Virginia. The Association is dedicated to teaching baseball and softball to all the county's youth. The Weston Democrat is the newspaper for Lewis County.

Publius Horatius Cocles leads the Romans in battle against the Etruscans, by Tommaso Minardi (1787-1871)

Publius Horatius Cocles leads the Romans in battle against the Etruscans, by Tommaso Minardi (1787-1871)  Samuel Ellsworth Winslow 1862-1940

Samuel Ellsworth Winslow 1862-1940

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.