Sam Winslow

If the companions of our childhood should turn out to be heroes, and their condition regal, it would not surprise us. [1]

--Ralph Waldo Emerson, Representative Men

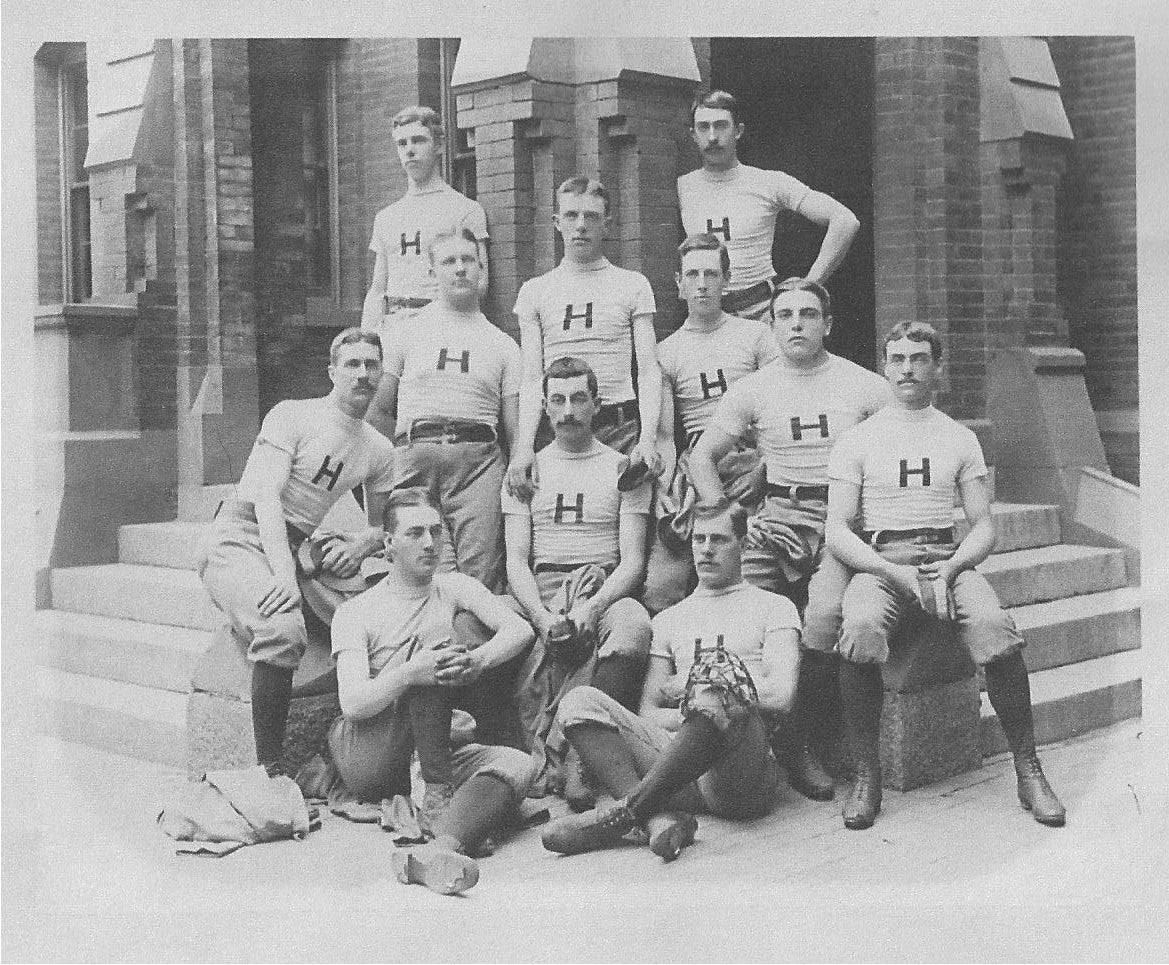

Photo courtesy of Harvard University Archives; HUP Winslow, Samuel E.

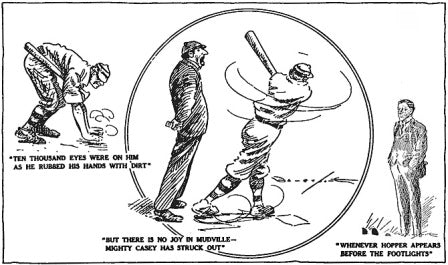

Sam and Casey

For most of his life, when Ernest Thayer was asked about the origins of "Casey at the Bat," he was quick to respond "Sam Winslow." Only in the last decade of his life would Thayer modify--in a significant way--his public version of how "Casey" had emerged from his youthful imagination. But there is no doubt that Thayer's boyhood friend and college classmate provided Thayer a vivid template of a modern hero.

Winslow and Thayer at Harvard

At a separate table in the dining room in Harvard's Memorial Hall sat the athletes. Phinney Thayer, though no sportsman himself , would have been welcomed to this table by the energetic Sam Winslow, Phin's childhood friend and high school classmate. Sam would have been equally welcome to take his dinner with the Lampoon staff, of which he was a member, or with the lively society of the Hasty Pudding Club among whom he and Thayer were also numbered, and for whom the multi-talented Winslow served as Theatrical Manager.

Samuel Ellsworth Winslow (April 11, 1862 - July 11, 1940) had graduated a year earlier than Ernest from the Classical & English High School in Worcester. His father--also Samuel--was a manufacturer of skates in Worcester and also engaged in local politics, serving as Mayor from 1886 to 1890. Samuel, Jr. spent a year at the Williston Seminary in Easthampton before entering Harvard, joining Thayer there in 1881. "A born leader," as Thayer described him, Sam was one of thousands of young men born during the early years of the Civil War with the first or middle name, "Ellsworth." Never was a name of honor more aptly bestowed on a boy born in 1862.

A Hero's Legacy

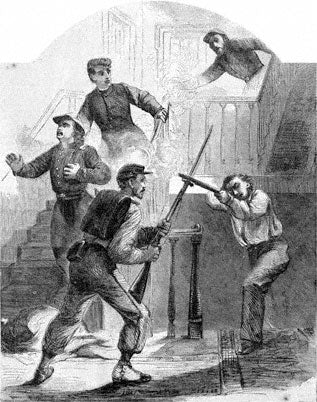

Colonel Elmer Ellsworth (1837-1861) was a remarkable young man who clerked in Lincoln's Springfield law office, assisted Lincoln's 1860 Presidential campaign, and recruited and trained one of the first elite volunteer units in the Union army, the "Fire Zouaves," New York's 11th Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Killed in a May1861 skirmish in Alexandria (just across the river from Washington, D.C.) and mourned not only by the Lincoln family but by Unionists throughout the North, Ellsworth was the first well-known casualty of the Civil War.

Death of Colonel Ellsworth, from sketch in Harpers Weekly, June 15, 1861; courtesy of the Gilder Lehman Collection, New York (#GLC 00623)

Historian Adam Goodheart, diligently searching the 1880 census via Ancestry.com, identified over 20,000 Americans born during the Civil War with the first or middle names of "Elmer," "Ellsworth," or "Elsworth." Goodheart estimates that if anything, this figure, like the census itself, represents an undercount.

As Goodheart observed of Ellsworth's fame before the War: "Never before had any American become famous and adored not for any particular accomplishments--not for being a poet or an actor or a war hero--but simply for his charisma." After his death, a shattered Lincoln mourned as Ellsworth's body lay in state in the East Room of the White House. For the Union at large, "Ellsworth's death released a tide of hatred, of enmity and counterenmity, of sectional bloodlust that had hitherto been dammed up....It was Ellsworth's death that made Northerners ready not just to take up arms but actually to kill."(2)

Captain of the Nine

By the time he entered Harvard in 1881, Sam's reputation and skills as a baseball player qualified him to captain the freshman nine. In his sophomore year he moved up to the varsity squad, and in his junior year he played both as pitcher and outfielder.

In the fall of 1884, the beginning of the senior year for Winslow and Thayer, a serious football injury to the captain of the baseball nine led to Winslow's selection as substitute captain. Thereafter Sam's true genius as a trainer and organizer manifested itself. During the winter of 1884-85, Winslow drilled the team not only in the indoor batting cage, but also introduced cross-training in the form of handball practice--no doubt enhancing the team's defensive speed and agility. As spring arrived, Winslow set up nets outside which served as backstops for batting practice, and insisted on extra workouts in accordance with his maxim, "Batting wins ball games."

The outlook for the 1885 campaign looked auspicious when Harvard won its first seven games, scoring an average of ten runs per game. Then on May 4 the tough Cochituate amateurs came to Cambridge and embarrassed the Harvard nine by holding them to one run, while scoring three. Winslow then demonstrated the maturity and creativity of his leadership by engaging the Cochituates' superb pitcher, a man by the name of Bent, to pitch to the Harvard team each afternoon until the batters learned how to hit his best stuff. By the time of the game with Yale in New Haven on May 16 (won by Harvard 12-4), the confident Harvard batters thoroughly intimidated the opposition.

President Eliot Requires a "Chat"

Winslow, a year older than most of his classmates, turned twenty-three in the spring of 1885. He took his responsibilities as coach, trainer, and player equally seriously and was not afraid to suspend one of his best players on June 12, with crucial games approaching, for an infraction of training rules. Because this sort of discipline had never been imposed on players at Harvard, college President Charles Eliot called Sam into his office for a chat. As recalled years later by one of Sam's classmates, Eliot opened the interview by asking Sam why he had taken such extreme measures to suspend a teammate. Sam, not at all intimidated, patiently explained the circumstances and his reasons, after which Eliot exclaimed, "Winslow, you did just right, and you deserve to win!"[3]

An Unparalleled Record

Winslow's Nine clinched the conference championship in Cambridge in a close game with Brown on June 15 with a run in the top of the ninth (in those days the order of which team batted first was determined by coin toss). Thereafter, the Harvard men were unstoppable on the way to a record of 27 and 1 for the year, with a massive celebration in Harvard Square and in the Quad following a second victory over Yale on June 20.

Harvard - Yale game in progress, June 20 1885, Holmes Field, Cambridge. An estimated 6 to 8,000 spectators were in attendance, including at least 1,500 women. Harvard prevailed 16-2.

Congressman and Mediator

Winslow went on to play a major role in the local and state Republican party in Massachusetts, then was elected in 1912, and for five succeeding terms, to the U.S. Congress. President Coolidge appointed him in 1926 to the U.S. Board of Mediation (now the National Mediation Board) where he would serve until 1934. Both he and Thayer would live until 1940: Winslow died on July 11 in Worcester, and Thayer, then living in Santa Barbara, California followed him on August 21.

Was Sam Winslow the "Real" Casey?

Thayer's post-graduation references to Sam Winslow, the Class of '85 "nine," and his tribute to the "great Harvard team" that pulled out every win, even when the game seemed lost, raises a further question.

If "Casey" had been intended (as in Thayer's later interviews with the press) as a memorial to Sam Winslow's leadership of the immortal "nine" of the Class of '85, the ballad was certainly a very edgy kind of tribute. The poem raised stratospheric expectations on the part of the Mudville crowd to "fever heat," then dashed them to utter despondency. "Gee, thank you, I suppose?" might have been Winslow's bemused response to later recitations of "Casey" in his honor at Class of '85 reunions. Is it possible that Thayer wanted posterity to believe that "Casey," which if nothing else has been understood as a poetic commentary on the perils of hero-worship, was in fact based upon his own worshipful admiration of his classmate Sam Winslow?

We can't rule out Sam Winslow as a model for The Mighty Casey. But in later posts we'll find an historical Casey from Thayer's own schoolyard days in Worcester. And we'll discover some even more formidable candidates for "Casey"--both real and legendary--who resided in Thayer's memory and imagination.[1] Ralph Waldo Emerson, Representative Men (p. 9). Kindle Edition.

[2] 1861: The Civil War Awakening (New York: Vintage Books, 2012) pp.286-291.

[3] Harvard University Class of 1885 Secretary's Report VIII (1915), in Jim Moore and Natalie Vermilyea. Ernest Thayer's "Casey at the Bat:" Background and Characters of Baseball's Most Famous Poem (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc.), 1994, pp. 130-131.

Cover photo: The 1884 Harvard Nine on the steps of Matthews Hall. Substitute captain Winslow is in the middle row, 2nd from right.

1 comment

Sam was my Great Grandfather. Thanks for writing this story.

John Winslow Peters

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.