![Take Me Out to the Ball[ot] Game -- Baseball, Women's Suffrage, and Trixie Friganza](http://caseyatthe.blog/cdn/shop/articles/Suffragette_Trixie_Friganza_NY_George_Grantham_Bain_Collection.jpg?v=1603296892&width=500)

Take Me Out to the Ball[ot] Game -- Baseball, Women's Suffrage, and Trixie Friganza

Ricardo,

The following story is from today's Wall Street Journal. Interesting to learn that TAKE ME OUT TO THE BALL GAME had its inspiration from a vaudeville star named Trixie Friganza. Anyway, no surprise that sports and politics have been forever entwined. From Hitler's '36 Olympics to Colin Kaepernick's kneeling during the national anthem and everything in between have the two attempting to promote their agendas.

I hope this can somehow find a niche in your Blog if you haven't done so already.

Buenos nachos

Mal Gosto

When Women and Politics Took Over Baseball

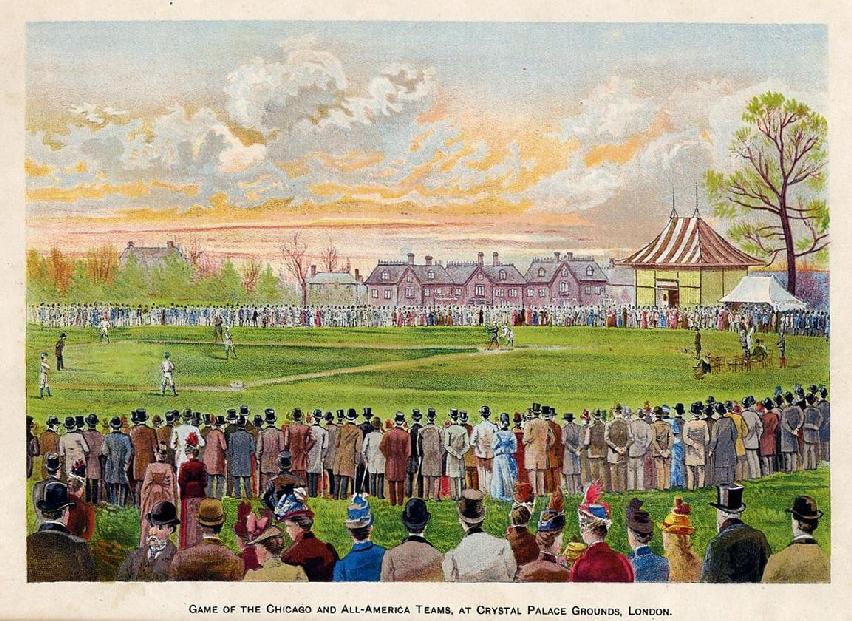

Activism in sports isn’t new. More than a century ago, suffragists lobbied for the vote at big-league ballparks.

A group of women advertising the ‘Suffrage Day’ baseball game between New York Giants and Chicago Cubs in May 1915.

By

Rachel Bachman

The women’s suffrage movement languished through much of the 1800s, its leaders depicted as droning and dowdy. But the early 1900s brought a rebranding: Spry women in sashes. Sleek motorcars. Massive parades.

And baseball.

“Please tell your traffic cops if they see a streak of green and white and purple whizzing along at forty miles an hour…not to arrest the streak for scorching,” a May 1913 New York Tribune story declared. The blur would merely be a car full of women speeding to the Polo Grounds “to convert the pitchers and catchers and umpire and the ‘fans’ and all the rest of the game to suffrage.”

Some fans say this 2020 year of social activism has sullied sports, a realm they view as politics-free. But leading up to 1920, suffragists orchestrated what might have been the most overtly political push in pro sports history: They swarmed baseball games as part of their successful campaign to amend the U.S. Constitution and give women the vote.

Suffragists sold tickets “by the thousands” for a July 7, 1915, “suffrage day” game at the Philadelphia Phillies’ Baker Bowl and promised packed stands, according to the Harrisburg (Pa.) Telegraph. They decorated the stadium with yellow streamers and pennants and handed out hand-held fans that read “Votes For Women” to “help to stir up the suffrage atmosphere for the human fans.”

A Sept. 16, 1915, game at the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Forbes Field benefited a women’s-vote group, and the suffragists made it more interesting: They pledged to pay $5 to every player who scored a run.

It’s no mystery why suffragists were drawn to the ballpark. Baseball was hugely popular in the early 1900s, especially among the swelling populations of East Coast cities. Crowds at games were overwhelmingly male, which was part of the suffragists’ strategy. They needed to win over the people who could vote to give them the vote.

Mary Newcomb, daughter of Sen. Newcomb, sells tickets to ‘Suffrage Baseball Day’ at the Polo Grounds.

PHOTO: GEORGE RINHART/CORBIS/GETTY IMAGES

The campaign’s full force was unleashed in a May 18, 1915, game between the Chicago Cubs and New York Giants at the Polo Grounds. New York was a pivotal state in the drive to pass the 19th Amendment and suffrage leaders, many of them college-educated and married to prominent New York City men, leveraged their advantages.

Behind a flurry of promotion for the game was George Creel. A former newspaper editor and publisher, Creel would later be appointed by Woodrow Wilson to head the U.S. Committee on Public Information, the government’s propaganda arm during World War I.

Creel was chairman of publicity for New York state’s Men’s League for Woman Suffrage, a group whose members included banker/philanthropist George Foster Peabody and sportswriter Grantland Rice. Men were crucial to the suffragists’ campaign, said Brooke Kroeger, author of “The Suffragents.”

“They controlled all the avenues of power, so of course they were important,” Kroeger said.

A cartoon showing two female baseball players, ‘Feminism’ and ‘Suffrage,’ with ‘Feminism’ saying, ‘Bean him!’ to ‘Suffrage.’

PHOTO: DONALD MCKEE

For the Cubs-Giants game, suffragists took 8,000 tickets and 125 boxes on commission, formed teams of nine (naturally) to hawk them and offered prizes to the fastest sellers in each New York borough.

They draped the ballpark in the decor and ceremony of their suffrage parades and rallies. Weeks before the game, Mrs. Norman de R. Whitehouse, head of the “votes for women baseball committee,” presented the Giants with a beribboned bat made of yellow wood and inscribed with “Vote for Woman Suffrage November 2, 1915,” according to the New York Tribune.

“Larry McLean has promised to use it the first time he goes in to pinch hit,” the story said. The line was an inside-baseball joke. McLean was a bruising 6-foot-5 catcher with a taste for corn whiskey who, days after the suffrage game, would be kicked off the team for brawling with Giants manager John McGraw in the lobby of a St. Louis hotel.

Despite boasting some influential supporters, women’s suffrage faced stiff opposition. In 1915, the Women’s Anti-Suffrage Association of Massachusetts distributed a booklet with the Boston Braves’ and Red Sox’ schedules and “some nutshell anti-suffrage arguments,” according to the Berkshire (Mass.) County Eagle. Numerous attempts to pass the women’s vote in individual states failed, including a 1915 effort in New York that preceded its passage two years later.

Even the athletes that suffragists cheered in that celebrated New York game were against them. According to the New York Tribune, “a poll of the Giants showed that the baseball players were almost unanimous in their opposition to votes for women.”

Suffragists nonetheless made their mark on the game. The seed of their baseball campaign might have been planted several years earlier as New York songwriter Jack Norworth carried on an affair. The object of his affection was vaudeville star Trixie Friganza, whom he was seeing in the spring of 1908, when he spotted inside a subway car a sign reading, “Ball Game Today—Polo Grounds.”

Inspired, he wrote a rousing tune in waltz time, copyrighted it and published song books with Friganza’s photo on the cover. Friganza also was a high-profile suffragist. That’s according to George Boziwick, retired chief of the Music Division of The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, who curated a 2008 library exhibit on 100 years of baseball music.

An image of the cover of ‘Take Me Out to the Ball Game’ from the digital collections of The New York Public Library.

PHOTO: THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY

Norworth’s song features a baseball-mad character named Katie Casey, who spurns her boyfriend’s offer to go to a show so she can sit in the stands and “root for the hometown crew.”

At the time, it was nearly as unusual for a woman to attend and cheer at a baseball game as it was for her to vote—in the few states that allowed it. But Norworth’s song was a hit, and spawned a wave of copycat tunes about bringing your girl to the ballpark. A few years later, newspaper columns began filling with stories about suffrage-day baseball games.

Norworth never said whether Friganza was the inspiration for the Katie Casey character in the song but, Boziwick said, “I think there’s a good likelihood that she is.”

The song’s first verse is long forgotten and rarely sung. But the chorus has become so well known, it’s hard to imagine nine innings without it.

It begins: “Take me out to the ball game…”

Corrections & Amplifications

“Take me out to the ballgame” is the start of the song’s chorus. A previous version of this story said it was the second verse. Also, the last name of George Boziwick was misspelled on second reference. (Corrected on Oct. 18.)

Write to Rachel Bachman at rachel.bachman@wsj.com

Copyright ©2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.