The Love Song of E. "Phineas" Thayer

The Love Song of E. "Phineas" Thayer, was awarded Honorable Mention in the Print/Online Article category of the 89th Annual Writer's Digest Writing Competition. The fully illustrated version of this article (with minor edits) can be found within Caseyatthe.blog at this link: The Love Song of E. "Phineas" Thayer .

"I do not believe that an artist's life throws much light upon his works. I do believe, however, that, more often than most people realize, his works may throw light upon his life."--W. H. Auden

Caseyatthe.blog explores enigmas which when unveiled reveal much about Ernest Thayer's idiosyncratic creativity and about the literary and cultural landscape from which "Casey" sprang to life. From this perspective, "Casey at the Bat" emerges not just as an entertaining poem whose cadences have been treasured by baseball-lovers over the past thirteen decades--but as a true Ballad of the Republic.

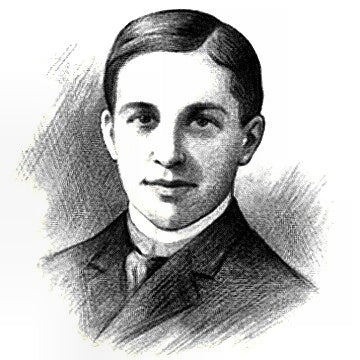

Ernest Lawrence Thayer (1863-1940) Harvard Class of 1885

But the most interior of these nested puzzles reveals Thayer himself as a young man--as discovered in episodes which deeply furrowed his young life, and which as he grew older he would rather have preferred to forget. The literary origin of "Casey" owes much to this heretofore unrecorded romantic drama-- whose origins may lie as far back as Thayer's junior year at Harvard College.

The Contest of Wit vs Strength

Much of Thayer’s better juvenilia discussed young love.-- A. M. Juster

"Casey at the Bat" would emerge as the last of a series of Sunday humor columns to appear in the pages of the San Francisco Examiner in 1887 . The dramatic prelude to the series of ballads published by the Examiner in the fall of 1887 was versified in the Harvard Lampoon edition published on January 4, 1884, under the title "Wit vs Strength." Jim Moore and Natalie Vermilyea, and later A. M. Juster, receive credit for having rescued those verses from the Lampoon archives in which they had reposed for eleven decades. Without them, a vital clue to Thayer's biography would have been lost.

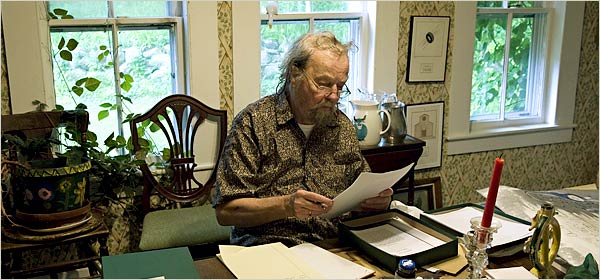

Poet and translator A. M. Juster has contributed to Light poetry magazine (June 2013) what Caseyatthe.blog acknowledges as the definitive "Casey" essay. In "Casey at the Bat' and its Long Post Game Show" (June 2013), Juster delved with a poet's perspective into the background of Thayer's most famous ballad with a critique of his early work as displayed in the Lampoon:

Thayer wrote at least 11 credited poems for the Lampoon, and probably deserves full or partial credit for some of the anonymous work. Almost equally bad was “Wit vs. Strength,” three quatrains in heroic couplets that emphatically argue without wit or apparent irony that it is swell that modern men woo modern women with words rather than swords.

I defer to Juster on the poetic merits of Thayer's early work, yet I confess my heart skipped a beat when I read Juster's judgment of "Wit vs Strength." Because I had found in these otherwise unpretentious verses a vital clue to the origin of Thayer's romantic contretemps in 1887--and to the tragedy which would ultimately ensue. But--aside from poetic merit--at least I think Juster will agree that the relative formality of "Wit vs Strength" lends the poem a certain gravitas which is missing in most of Thayer's Lampoon writing.

I.

Once maids were won by strength of arm, and deeds

Of war and might. The man of words must needs

Content himself as counselor or fool.

Wit goes unmated when the strong men rule.

II.

The modern maid by wit is stormed and carried;

Poor, dullard strength, for her, may go unmarried.

The jester Time has wrought a change extreme,--

Now strength's the bachelor, and Wit's supreme.

III.

Wives able champions for their mates desire,

And different weapons different times require;

Once swords were used, and strength to wield them needed;

But now wit's mightier, and the sword's succeeded.[1]

With hindsight obtained from Thayer's series of eerily topical ballads published during the fall of 1887, and now with the added evidence of "Wit vs Strength," we may infer that Thayer's infatuation with classmate Genie Lent's sister may date as far back as the boys' junior year (1883-84) at Harvard. We know the Lent family were accustomed to spend the winter "season" in New York City during these years, and it is easy to suppose that Genie had invited his Lampoon pals, including Thayer and boyhood friend William Randolph Hearst, to join him in New York during their vacation. Bill Lent, the family patriarch, was one of the original 49'ers--a successful gold and silver miner, a friend of George Hearst and a sometime partner in Hearst's enormously successful ventures. William Randolph and "Genie" were boyhood friends, accompanying their mothers on overseas tours and annoying hotel managers across Europe with their destructive pranks.

Could a holiday encounter between Ernest Thayer and his pal Eugene's sister have inspired the stanzas of "Wit vs Strength," published in the Lampoon just after the New Year in 1884? If so, an episode during a rare interval in Fanny's young life untroubled by grief would have provoked Thayer's imagination with a theme drawn from the classics. From this point forward, shadows would fall between the young lovers. The following April, Fanny's older brother William would perish in a San Francisco park from a mysterious but likely self-inflicted gunshot wound. In the spring of 1886, Thayer accepted Will Hearst's invitation to write for the Examiner--where he pursued his courtship of Fanny and wrote to his sister of his matrimonial aspirations. As a balladeer, Thayer would return in his Examiner columns during the eventful year of 1887 to explore the darker themes of love's trials and torments--each framed as romantic triangles.

Though its light, confident tone belied the theme of "Wit vs Strength," Thayer's poem evoked an ancient contest of two men fighting over one woman. This is the essence of Homer's epic, which tells the story of the war between the Achaeans and the Trojans over the abduction of Helen. But the Iliad's key plot line--far more personal than political--is driven by the wrath of Achilles over the appropriation of Achilles' trophy, the "fair-cheeked" Briseis, by King Agamemnon.

In his verses the classically-educated Thayer claimed that conditions have changed since those ancient times-- modern women are now to be won by wit and words. None of Thayer's Harvard classmates were sword-slingers even in a metaphorical sense, but a certain West Point instructor had already made his appearance--a bona fide warrior even though the artillery officer's sword of that era was mainly ceremonial. Already known in the Lents' circle, Lieutenant Walter Alexander had grown up in San Francisco and would likely have been one of the group of regular visitors to the Lents' New York residence.

With this adversary Ernest Thayer would contend for the affections of Eugene Lent's sister. In the drawing room of the Lent family's elegant New York apartment, it is easy to imagine the plodding mathematics instructor, some seven years older than classmates Genie (Fanny's younger brother) and "Phinney" (short for "Phineas," Thayer's college nickname), bested by jibes of the high-spirited Harvard men. And knowing Thayer as we do, we can identify the principal advantage held by Phinney in this contest: he was always able to make Fanny laugh.

In light of Thayer's romantic misadventures from 1884 through 1887, we can further speculate that the poet may well have offered his "Wit vs. Strength" to Fanny as a token of courtship. In a real sense, if "Wit" was Thayer's weapon of choice, and if he would wield his wit through verse, the poem itself would have scored well in Thayer's favor. "Wit vs Strength" would have appealed not only to Fanny's affections but also to her sense of humor. Whether Thayer had already presented Fanny his poem during the Christmas vacation of 1883, or whether he sent her a published copy in January 1884, we can guess that "Wit vs Strength" is one of the few surviving tokens of Thayer's unblemished infatuation with Fanny -- far different in tone from the acerbic ballads that would later appear in the Examiner.

Regardless of Thayer's poetic conceit, the elemental rage and jealousy of such contests could not be expunged by a modernized format. "Wit" and "Strength" referred merely to the choice of weapons: lust, envy, and wrath persisted as the primal motives in this contest, whether Thayer acknowledged it or not.

Rage — Goddess, sing the rage of Peleus’ son Achilles,

murderous, doomed, that cost the Achaeans countless losses,

hurling down to the House of Death so many sturdy souls,

great fighters’ souls, but made their bodies carrion,

feasts for the dogs and birds,

and the will of Zeus was moving toward its end.

Begin, Muse, when the two first broke and clashed,

Agamemnon lord of men and brilliant Achilles. . . .[2]

In light of the apparent defeat of "Wit" in the summer of 1887, when Fanny chose to marry the Lieutenant, we could regard Thayer's 1884 Lampoon poem as mere evidence of his naiveté. But through a poetic swerve that can only be described as sublime, Thayer's wit achieved a victory he could not have imagined as the poet / editor of the Harvard Lampoon. Phin would stake a modest claim to having written a ballad recounting a legendary contest evoking the aspirations of the American Republic. Thayer would upend the rollicking triumphalism of Thomas Macaulay's tale of ancient Rome with a tragic twist, challenging the self-reliant brand of heroism lauded by Emerson and deeply ingrained in American consciousness. In doing so, Thayer would appropriate the popular retelling of a Roman legend (Macaulay's 1842 epic poem "Horatius" based on Livy's history) to reformulate the ancient story in a manner the Greek tragedians would have applauded.

Later, in the series of ballads written during the fall of 1887, Thayer would echo an actual struggle in a contest pitting the attributes of "Wit" against those of "Strength." As a Harvard undergraduate, comfortably enthroned as the amiable bachelor President of the Lampoon, Thayer had confidently weighed in on the question: Wit, he wrote, would ultimately win out.

What Thayer did not learn at Harvard, but soon after graduation would have to confront in real life, is that there were some contests for male supremacy, and for feminine affection, in which neither Wit nor Strength would prevail. In the tempestuous period of 1886-87, Thayer wooed the lovely Fanny Lent; lost her to a West Point instructor, the son of a beloved Civil War general; and then--while still in "deep despair"--regained a tantalizing parody of hope when Fanny abruptly abdicated her role as an army wife and fled back to her family in San Francisco. Wit versus Strength, indeed! Weighing his options as a journalist in a competitive market, and in the bitter aftermath of his fractured romance, Thayer decided early in 1888 to return to Massachusetts. He and his Harvard pal Frederick "Fatty" Briggs traveled together -- Briggs to Springfield, Thayer to Worcester. They likely arrived just days ahead of the Blizzard of 1888 which would paralyze the East Coast and inflict over 400 fatalities.

Sitting alone in his study in Worcester as the brutal winter slowly gave way to spring, Ernest found the imagery--and the literary template--to articulate his loss and to focus his anger:

Then, like a wild cat mad with wounds

Sprang right at Astur’s face.

Through teeth, and skull, and helmet

So fierce a thrust he sped,

The good sword stood a hand-breadth out

Behind the Tuscan’s head.

--Thomas Macaulay, "Horatius," in Lays of Ancient Rome

As Horatius struck down the noble Astur, Thayer struck out Casey, and brought doom to Mudville. Whatever part Fanny Lent's troubled history had played in the background of this youthful drama, neither Wit nor Strength would claim victory in the contest that Thayer had imagined in the pages of the Lampoon. But the wisdom retained from this bitter struggle would serve Thayer well in months and years to come: Wit never yielded to an adversary in any contest as long as the poet could still wield his pen.

[1] From the Harvard Lampoon, January 4, 1884, quoted by Moore and Vermilyea, pp. 146-147. "Succeeded" is here used by Thayer in the sense of "replaced."

[2] Robert Fagles's translation of the Iliad, with introduction and notes by Bernard Knox (New York: Penguin Group {USA} Inc, 1990)

Cover Photo: Site of the former Holmes Field, Harvard College

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.