"The score stood four to two..."

College competition dominated the New York and Brooklyn sports pages in the early summer of 1884 when Harvard and Yale scheduled a tie-breaker to decide the Inter-Collegiate championship. Given the intense public interest in the outcome--tickets would go for double the normal price paid by locals for admission to professional games--the contest was scheduled at Brooklyn's Washington Park for June 27.

Among the 3,000 or so who would attend the game that day, accompanying the throngs of students and alumni of both schools, were "hundreds of ladies in exquisite toilets and smiling faces [who] added a rare charm to the place," according to the New York Tribune.

August 27, 1776. Outflanked by the British, Lord William Stirling and his rear guard of Marylanders launch a doomed attack in the background, while the rest of the army escapes toward American lines through the millpond and marsh to the right. The Vechte-Cortelyou House, the centerpiece of the Marylanders' rear-guard attack, is seen in the right background of the 1862 engraving (below, with the skating club located on the future site of Washington Park). --Courtesy of John Thorn, MLB's Official Historian

Scholars among the crowd might have recalled that Washington Park, the home field for the Brooklyn Atlantics, covered ground that had been bitterly contested on August 27, 1776 during the Battle of Long Island, often called the Battle of Brooklyn. The largest battle in North America to that time, the struggle among these swampy acres would nearly decide the fate of the young American army and of its commander, George Washington--for whom the baseball park would be named. In the intervening century, these hallowed fields had become a site where men would contend with bat and glove rather than with sword and musket.

The Vechte-Cortelyou house and farmyard in prosperous pre-war times. From 1883 to 1891 the house served as the clubhouse for the "Brooklyn Baseball Club," playing at nearby Washington Park, before they became the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Brooklyn and Long Island cradled the early years of baseball, where in 1855 amateur working-class teams like the Eckfords and Atlantics gathered to contend with the Knickerbockers and other New York clubs. John Thorn, MLB's Official Historian, dates baseball's "expulsion from Eden" (the end of the amateur era) to July 20, 1858[1], when the best New York and Brooklyn players met for the first all-star game, with the first paid admission, and in the first enclosed park (the Fashion Race Course). Proceeds of the game, which was attended by some 10,000 spectators, were divided equally between the New York and Brooklyn clubs and presented to the widows and orphans funds of the cities' respective fire departments.

The Yale and Harvard nines had played before large and enthusiastic crowds (paired, for example, at an exhibition game in Philadelphia the previous July) but perhaps never before with so much at stake. The ebb and flow of this hard-fought rivalry would be thoroughly covered by the New York press, including the Times, the Sun, the Tribune, the Herald, and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Louis K. Hull, the Yale oarsman who played on five undefeated Yale football squads from 1879 to 1883, led the Yale spectators, who were still celebrating yesterday's two-length victory on the Thames over the Harvard crew. Famed Harvard sprinter W. H. Goodwin, Jr. captained the Crimson cheering section.

As for the weather, it was a perfect day for the spectators -- clear and sunny, with a high temperature of about 76 degrees at the afternoon game time of 4 o'clock. But the field was dry and dusty. It hadn't rained in the New York area for two weeks, and then only a mere fraction of an inch. That meant the ground was hard, and balls hit into the outfield would bound and roll fast--which Harvard's center-fielder (and boyhood pal of Ernest Thayer) Sam Winslow was about to discover.

In the season's first match-up--an exhibition game between the two teams on May 10 in Cambridge--Sam Winslow and Edward "Nick" Nichols split pitching duties in an 8-1 loss. But in the games that would count in the standings, Harvard's fortunes turned. On May 17, Winslow pitched an 8-7 victory at New Haven; and on June 21 in an exhibition game in Cambridge, Nichols allowed only four runs in a 17-4 Harvard victory. With two regular season victories over the Bulldogs, and with Nichols chosen to pitch again, Harvard hopes were at their highest.

Years later, it was the May 17 contest in New Haven that 3rd baseman Walter Phillips, Harvard ’86, would remember as the real “red letter” game:

When Harvard went to the bat in the last half of the ninth inning (the choice of innings was then determined by tossing a coin, and not, as now, by a general rule) the score was 7 to 4 in favor of Yale. The atmosphere was very blue [the Yale color] and very enthusiastic. Then the thing occurred which endears the game of baseball to the American people. ‘Something happened’ and happened quickly. Harvard made four runs and won the game, with only one man out. The atmosphere changed from blue to crimson more suddenly than any of us have since seen it change.

When the team returned to Boston from their May road trip, after successive wins in Springfield and Amherst, Phillips remembered “We were met at the railroad station…by a brass band and ‘all the fixings,’” which then accompanied the team along Beacon Street to Cambridge with a popular demonstration including fireworks.

Now at Washington Park, Harvard also won the toss and would bat second. In the top of the first, Nichols retired Yale's first two batters. But when Yale center-fielder Bremner hit a daisy-cutter to right, the Harvard cheering faded. Worse, the Harvard battery succumbed to the jitters. Bremner took second on a passed ball, and went to third on Nichols' wild pitch. A base hit by the catcher Souther scored Yale's first run with a deafening response from the Yale bleachers.

In the bottom of the inning Harvard's batters were retired one, two, three; likewise the Yale batters at the top of the second. Now it was Harvard's turn to cheer: though Tilden struck out, Nichols and Allen atoned for their first-inning errors by hitting safely, occupying first and second. Winslow, next up, grounded out to the shortstop. But as the next batter, Smith, swung at what should have been a third strike, catcher Souther missed the ball, and attempting to throw the runner out at first, threw the ball into right field instead. Both Nichols and Allen scored on the error to give Harvard a 2-1 lead while the Crimson partisans yelled themselves hoarse.

Neither side scored in the third inning. In the fourth, Yale put two men on, but sloppy base-running ruined their chances. In the top of the fifth, Yale's Brigham hit a single and McKee followed with a base on balls. Pitcher Odell then hit into a fielder's choice, forcing Brigham out at third; but when Hopkins hit a double to right, McKee scored from second. Odell also ventured toward home but a great throw by right fielder (and team captain) LeMoyne caught him at the plate. But Yale had tied the game 2-2 and it was the Elis' turn to cheer.

When Harvard did not score in the bottom of the fifth, the game hung in the balance. In the sixth frame, Yale's second baseman Terry led off with a single. Bremner then hit a long ball to center, which bounded past Winslow on the sun-baked outfield, while Terry rounded second and headed to third. Winslow recovered the ball and threw to the cut-off man Coolidge at second, but Coolidge threw wildly to home, and Terry scored. Now it was Yale 3-2. Stewart then hit to left field which scored Bremner to “a perfect storm of applause” (wrote the Sun reporter): Yale 4, Harvard 2.

In the bottom of the sixth, Harvard's shortstop Baker took a base on balls, but was caught trying to steal second. Phillips and Tilden both struck out. Yale could not score in the top of the seventh; in their next turn at bat, Harvard hurler Nichols grounded out to the third baseman; catcher Allen struck out; and Winslow was retired at first on a neatly-fielded ball by Yale's second baseman Terry.

Neither team scored in the seventh, but the eighth inning would long linger in the memories of the spectators, undoubtedly including Winslow's pal Thayer. Thanks to the vivid detail of the Times reporting, we have an insider's view of the ensuing drama. In the top of the inning, Yale put four runners on base, but could not bring one home. Then, down to their last six outs, Harvard mounted a comeback. Leadoff batsman Smith hit safely to first. At this point Yale's veteran pitcher Odell, appearing in his second career championship game, began to tremble visibly as reported by both the Tribune and the Times. Odell appealed to his captain, Hopkins, to allow him to switch positions with right fielder Booth, but Hopkins turned him down with the exhortation: "You're doing nobly--keep it up!" With the support of his captain and teammates, Odell found a way to pull himself together. The next Harvard batter was LeMoyne: Odell walked him. With two men on, and nobody out, "a sickly silence" (as Thayer would aptly describe it) must have fallen over the Elis. But then for Yale came a flare of hope: Odell struck out Harvard's leadoff hitter Coolidge! One out, with two men on. The next batter up was Baker: Odell walked him. Now the situation indeed looked dire for the men in blue: the bases were loaded, with only one out. On the Harvard side, hope sprang eternal: a solid hit could bring at least two men home to even the score!

Walter Phillips now hit a bouncer to Odell, who threw Smith out at the plate as he bolted from third. There were two outs--with men on second and third--when the intrepid Tilden (who had not yet hit safely), "knocked a hot one to McKee at shortstop." But McKee fielded it cleanly and threw Tilden out at first. From the Yale bleachers came shouts of joy and relief while gloom descended upon their Crimson counterparts. And so the score stood four to two, with but one inning more to play, in Thayer’s long-remembered verse.

Samuel Ellsworth Winslow (1862-1940), pitcher, outfielder and 1885 captain of the Harvard Nine. Ernest Thayer often cited Winslow as his inspiration for "Casey at the Bat" -- but research suggests that Winslow was best remembered by his classmates as the intrepid pitcher, not as the ill-fated batsman! This image was painted by the talented and prolific Graig Kreindler (b. 1980), based on a photograph in the Harvard University Archives

In the top of the ninth, Yale could not score, though Stewart stroked a double. It was now the last chance for the Harvard nine. Nichols and Allen had both been retired when sturdy center-fielder Winslow came to the bat. His belated single offered the Crimson a last shred of hope--but Smith, following Winslow, popped up to Odell--who fittingly, given his struggle to master not only the opposing batsmen, but also his own nerves, gloved the final out.

The Yale nine were conveyed off the field on the shoulders of their jubilant classmates. For the Harvard men, and for their supporters, there was only the dismal train ride back to Boston. This time, there would be neither brass band nor fireworks: for Harvard, as for the colonial army of 1776, the Battle of Brooklyn had ended in defeat. But following that calamity, Washington's retreat—executed without loss at night across the East River, under the threat of British warships-- not only saved the army but taught its commander a series of valuable lessons. A dreadful battle had been fought and lost, yes--but Washington's army would survive to fight on. In this same way the consequences of an inter-collegiate contest--fought on the same field as that of '76--would not only set the stage for the 1885 Harvard campaign, but would ripple far into the future, through the wit and wisdom of a young man whose unique gift from the Muses was the alchemy to transform pathos into poetry.

Among the Yale cheering section that day, we can confidently imagine the presence of athletic freshman William Lyon Phelps. Lover of baseball both as player and life-long enthusiast, Phelps would go on to a distinguished career as Yale’s Lampson Professor of English Literature. His popular course in modern novels—a controversial offering, which upset his tenured peers—would be the first of its kind at Yale, and his engaging lecture style would bring acclaim from students if not from his envious colleagues. Before retiring in 1933, Phelps would be elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1921) and to the American Philosophical Society (1927). On the year following his retirement, Charles Scribner’s Sons published a small annotated anthology by Phelps, entitled What I Like in Poetry[2]. “Casey at the Bat” was among the favored selections, and in an introduction, Phelps delivered perhaps the most scholarly encomium that the ballad of “Casey” (as well as its author Thayer and foremost interpreter DeWolf Hopper) has ever received as a literary endeavor. Notably, Phelps demonstrated his classical insight into the poem by employing the word "tragedy" three times:

This graduate of Harvard University wrote a masterpiece which millions of ambitious men wish they had written. For "Casey" is absolute perfection. The psychology of the hero and the psychology of the crowd leave nothing to be desired. There is more knowledge of human nature displayed in this poem than in many of the works of the psychiatrists. Furthermore, it is a tragedy of Destiny. There is nothing so stupid as Destiny. It is a centrifugal tragedy, by which our minds are turned from the fate of Casey to the universal. For this is the curse that hangs over humanity--our ability to accomplish any feat is in inverse relation to the intensity of our desire. The declamatory art of DeWolf Hopper gave to this tragedy supreme unction.

Caricature of Yale's William Lyon Phelps (1865-1943), educator and literary critic. The drawing, by artist and illustrator Victor de Pauw, accompanied an anonymous biographical sketch most likely written by Phelp's former student at Yale, author Waldo Frank.[3]

"The score stood four to two..." would ever after bring a gleam to the eye, or a pang to the heart, of all Harvard and Yale partisans present at the Battle of Brooklyn on June 27, 1884. Thayer's empathy for a fellow underdog--and his intuitive empathy for the "broken edges of things," as recognized by fellow Lampoon contributor George Santayana--would allow the young artist to transcend his school loyalties to appreciate the late-inning heroics of the defending pitcher. Struggling against a formidable onslaught, yielding walks, and visibly tempted by his inclination to retreat, the Yale pitcher nonetheless stood fast to seal the victory for his team and his school. Here among the wrack of ancient battles were strewn all the makings of a future epic.

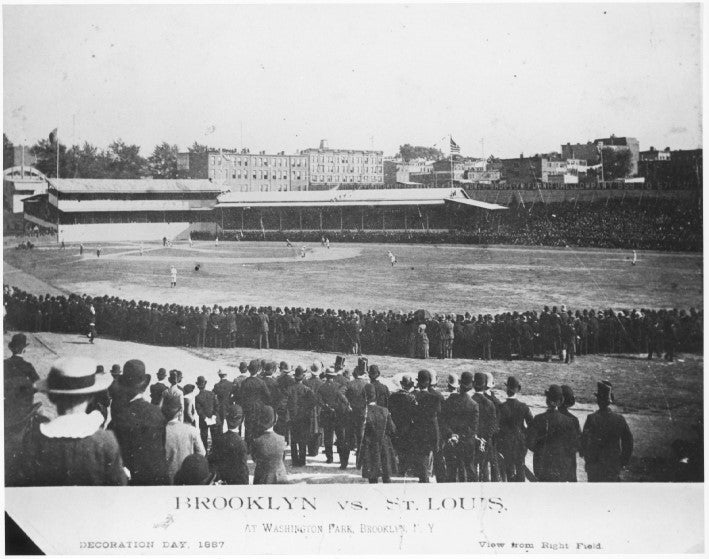

Washington Park, game between Brooklyn Grays and St. Louis Browns, 1887.

Washington Park, game between Brooklyn Grays and St. Louis Browns, 1887.

Courtesy of John Thorn, MLB’s official historian.

The official portrait of the 1884 Nine, posed on the steps of Matthews Hall, captures a somber mood--perhaps reflecting the disappointment of having lost the championship game to Yale in Brooklyn on June 27. Winslow is the second man seated on the right railing, immediately behind Allen, the catcher, identifiable by the mask perched on his left knee. The lanky Nichols, pitcher of record in that championship game, would dominate the Inter Collegiate competition the following year. He stands in the center of this photo, his hands resting on the teammate in front of him.

[1] John Thorn, Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2011) pp. 116-121.

[2] William Lyon Phelps, What I Like In Poetry (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1934), p. 16.

[3] "Search-Light," Time Exposures: Being Portraits of Twenty Men and Women famous in Our Day (New York: Boni & Liveright, 1926), pp. 23-28.

#CaseyattheBat #ErnestLawrenceThayer #SamWinslow #SamuelEllsworthWinslow #HarvardBaseball #HarvardYaleBaseball #WilliamLyonPhelps #WashingtonParkBrooklyn #BrooklynBaseball #BattleofLongIsland1776 #BattleofBrooklyn1776 #1776 #BrooklynHistory

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.