The Strange Romance of a Bold Detective

By far the best of Thayer's 1887 "pre-Casey" ballads was "The Strange Romance of a Bold But Unfortunate Detective," published in the Examiner on Sunday, November 20, 1887. It is also perhaps the most poignant of Thayer's ballads exploring variations on the theme of romantic triangles--because the two contestants for the love of "Lizzie Fay" represent conflicting identities assumed by a single character--the detective himself.

"The Strange Romance" suggests an actual duality with which the ballad's author was uncomfortably familiar. Thayer, the youngest son of a well-to-do clothing manufacturer, was living in post-graduate poverty in San Francisco, sharing rooms with a former classmate and working as a columnist and reporter for the Examiner. Phin had borrowed money from his brother Edward, and evidence suggests that like the prodigal son of the proverb, he may have squandered it in the get-rich-quick speculation common to the Gilded Age, perhaps on a failed magazine venture. The "wealthy family / prodigal son" narrative suggests one troubling incongruity of Thayer's situation in the fall of 1887.

Likewise, Thayer clearly suffered from the "will she / won't she" ambivalence regarding his former girlfriend's affection and availability following her unexpected return to San Francisco in September. Though Thayer had characteristically mined romantic conflict for the content of his ballads, the comic potential of his own situation--even for this self-deprecating humorist--would eventually have been exhausted.

Even more dramatically, the Examiner reporters themselves--Thayer among them--were being delegated various undercover assignments throughout the Bay area requiring them to gather information undiscovered by, unreported by, or deliberately concealed by, the official information-gathering agents of the police.

San Francisco Police, 1890 "Raiding Squad"

Hearst's Examiner ran a self-congratulatory editorial on October 30, 1887 proclaiming the newspaper was "especially proud of the bright young men who keep it informed of everything that happens locally and incidentally give Justice a lift when her chariot gets mired down." In effect, Hearst had set up his "bright young men" as a kind of vigilante detective force: "Whether a child is to be found, an eloping girl to be brought home, or a murder to be traced, one of our staff is sure to give the sleepy detectives their first pointers."

The tools of detection had in fact been turned by the Examiner against the police and civilian bureaucracies themselves:

The police and detectives have not only been outdone at their own profession, but they have been unable to protect themselves from the same power of research that has proved so disastrous to lesser criminals. The Examiner's young men eluded all the might of the Police Department and marshaled the secret crimes of the 'upper office' in a public review.

A "Strange Romance" and the Divided Self

"...I thus drew steadily nearer to that truth, by whose partial discovery I have been doomed to such a dreadful shipwreck: that man is not truly one, but truly two." -- Robert Louis Stevenson, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886) Samuel Clemens/Mark Twain (with his own curiously bifurcated personality), William James, and Ernest Thayer shared with Stevenson the Late Victorian fascination with the "divided self."

Based on the dramatic encounter in Phin's November 20 ballad, "The Strange Romance of a Bold But Unfortunate Detective / Faithless Lizzie Fay / A Versified Warning to the Too Efficient Officers in the Secret Service," it is easy to imagine any number of day-to-day episodes from which a rendezvous with a "pretty waiter girl" like the fictional Lizzie Fay might have been drawn. The story of a coffee house enchantress could have emerged from Thayer's own experience as an enterprising reporter on the staff of the Examiner , collecting evidence on a missing person or documenting malfeasance on the part of an elected official. In his newspaper role, Phinney's experience of San Francisco would have been far different from that of rubbing elbows with the "nobs" of Nob Hill--such as occasional lunches with William Randolph Hearst and his mother Phoebe at the elegant Palace Hotel, or dinners with classmate Eugene Lent's family in their gracious mansion at Polk and Eddy Streets.

Barbary Coast district, San Francisco

Young Phin would have been vulnerable to the enchantment of a "Lizzie Fay," one of thousands of young women employed in the restaurants, saloons, and coffee houses of Gilded-Age San Francisco. But a more obvious example of a young gentleman's temptation to adopt a double life with an "incomparably fair" waitress (who in the ballad was also an excellent cook and baker) was provided by the Examiner's publisher, "Billy Buster" himself. The cosseted son of one of America's wealthiest tycoons, the prankster expelled from Harvard, the Examiner's publisher William Randolph Hearst lived at this time across the bay in Sausalito with Tess Powers. Billy was so attached to Tess, a former Cambridge waitress, that he had defied his mother by bringing Tess along with him to San Francisco.

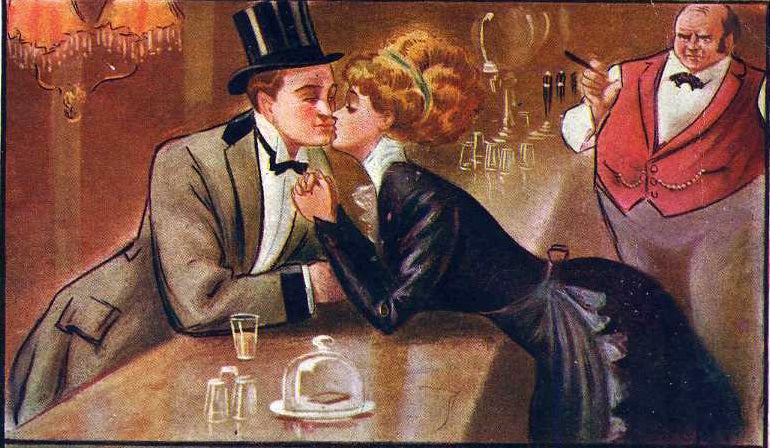

"A singularly noticeable appetite for cake" -- illustration for "The Strange Romance" from the San Francisco Examiner, November 20, 1887

The "bold detective" in Thayer's "Strange Romance" had encountered "Lizzie Fay" in his original identity as "Peter," as the detective explains to the narrator:

Just at present I am Peter, but to-morrow I may be

Quite an altogether diff'rent individuality:

And I do this sort of business so miraculously well,

That Peter, sir, is frequently a victim to the sell.

Thayer employed "sell" here in its meaning as "hoax" or "deception," illustrating a commonly-observed tendency that those who are skilled at deception are also frequently deceived. Also worth noting here is Thayer's unique use of "individuality," the word employed in the place of the more commonly-used "personality," but in the context of the ballad, suggesting the deliberate juxtaposition of both "individual" and "duality."

They call me a detective, as you're probably aware,

But what I really am I cannot positively swear;

For in practicing detecting many cases will arise,

When it's requisite to go about the country in disguise.

Here the unfortunate detective is attempting to explain the breakdown that has laid him, raving with fever, in his sickbed. Ominously, he reveals doubt as to "what I really am," which is a key symptom of what we might term Peter's personality disorder.

The immediate cause of the detective's breakdown, we are given to believe, is Peter's infatuation with the "sweet enchantress" Lizzie Fay, who bakes the coffee cake the detective ardently devours.

As Peter, the detective is "smitten by the charms of Lizzie Fay" as well as by her coffee cake and mutton cutlets. "And finally," reveals the patient, "she suffered me, as Peter, to embrace / Her lovely little figure and her pretty little face."

Like French painter Edouard Manet, who painted this scene in 1882, Thayer had likely visited the bar at the Folies-Bergère during his post-graduation trip to Paris in 1885-86. Was Thayer the victim of a "strange romance" with one of San Francisco's "pretty waiter girls"?

Then came the inevitable turn of circumstances driving the story, one worthy of fellow Examiner columnist Ambrose Bierce's mordant view of human experience. Thayer's detective "...retired from being Peter and assumed the role of Bill." But in his newly-assumed identity as "Billy," and driven by the appetite he shares with his alter ego, the detective happens upon the identical coffee house "Where, as Peter, it had been my cherished habitude to eat." Naturally, Billy begins to chat up Lizzie Fay, and eventually, Billy also wins her embrace:

And, as Billy, I was very, very jubilant until

I resumed the role of Peter and gave up the role of Bill:

But when, as Peter, I returned to Lizzie as of old,

I found that she'd become to me, as Peter, very cold.

She said that our relations could no longer be the same,

That her heart it was another's, and that Billy was his name;

Then I saw that I, as Billy, had performed a traitor's part,

For I'd robbed myself, as Peter, of the darling of my heart.

The conundrum of the detective's competing identities is not resolved as in a Shakespearean comedy, but rather leads Peter to want to murder Billy--a resolution which the detective would have carried out but for his "horror of committing suicide." As his identities wrestle with each other in this crisis, the detective loses consciousness, later recovering to recount his sad tale:

"...I nursed him through a fever which resulted from the blow..." --illustration from "The Strange Romance" in the Examiner, November 20, 1887

My name, I'll add, is Peter as you very likely know;

I am sure that it is Peter, for my mother told me so;

But it might as well be James, Augustus, Jonathan, or Paul,

For to all intents and purposes I'm nobody at all.

Thayer provides his unique "broken-edge" dénouement to the story, with the detective's revelation that he is no longer certain of his real identity: "...to all intents and purposes I'm nobody at all." The tragedy of lost romance had led to a crisis of identity, and to a disintegration of the "bold detective's" personality.

It is easy to imagine a Rod Serling adaptation of this final scene (as Serling did adapt Bierce's "An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge") with the bedridden detective plaintively grasping his caregiver's lapels, demanding to know "Who am I?" As the scene fades, and as Serling appears through the San Francisco fog, casually smoking a cigarette in front of the coffee-house window, behind the glass we see Lizzie affably pouring coffee for another customer. Serling would suggest to us, the audience, that the better question for the detective to have asked would be "Where am I?" The rejoinder, for Serling's Twilight Zone devotees, would have been obvious. For Thayer's audience in the fall of 1887, the catharsis would have been equally dramatic, provoking at least a recognition of the hazards of role-playing that love often demands of its protagonists.

Here, then, is Thayer's Ballad of "The Strange Romance of a Bold but Unfortunate Detective:"

Oh, I know a sweet enchantress by the name of Lizzie Fay,

And she does a rushing business in the cake and coffee way;

Her pies they are a poem, and her doughnuts are a spell,

And she cooks a mutton cutlet most astonishingly well.

And I know a bold detective who was formerly in love

With the lady whose attractions I've alluded to above;

He used to worship Lizzie, and he'd frequently partake

Of his weight in Lizzie's coffee and his bulk in Lizzie's cake.

But that Lizzie didn't treat her suitor properly I know,

For I nursed him through a fever which resulted from the blow,

And I listened to his ravings as I stood beside his bed

Occupied in pouring water on his incandescent head.

"Oh, Lizzie, darling Lizzie," he would piteously call,

"Is it possible you really didn't care for me at all?

Come and frown upon me, Lizzie; twine your fingers in my hair,

And assert your young affections in a cold, repellent stare."

And I suffered from a morbid curiosity to find

What the nature of the trouble was that preyed upon his mind;

For I'd never known a lover to request his lady fair

To assert her young affections in a cold, repellent stare.

So I bled the bold detective, and I buried him in ice,

And I got from him the very best of medical advice;

And I dosed him and I nursed him with a perseverance grand,

For my morbid curiosity was more than I could stand.

It is not at all unlikely I'd have perished in his stead,

If he hadn't providentially recovered of his head;

But it happened that his fever took a f{avorable} turn,

And I got from him the story I was s{uffering} to learn.

"My name," he said, "is Peter, as you very likely know;

I am sure that it is Peter, for my mother told me so;

But it might as well be James, Augustus, Jonathan or Paul,

For, to all intents and purposes, I'm nobody at all.

"They call me a detective, as you're probably aware,

But what I really am I cannot positively swear:

For in practicing detecting many cases will arise,

When it's requisite to go about the country in disguise.

"Just at present I am Peter, but tomorrow I may be

Quite an altogether diff'rent individuality;

And I do this sort of business so miraculously well,

That Peter, sir, is frequently a victim to the sell.

"Indeed, the only common trait in all the roles I take

Is a singularly noticeable appetite for cake;

And this hankering for cake, sir, plus a tenderness for smelts,

Is my only means of knowing that I ain't somebody else.

"Now I used to go, as Peter, to a coffee-house in town

Where they have a way of doing cake particularly brown;

And it happened that the lady who attended on me there

Was emphatically youthful and incomparably fair.

"And, as Peter, I was smitten by the charms of Lizzie Fay,

And, as Peter, I would go to see her nearly every day.

And my heart, as Peter's heart, sir, being amorously fired,

I would eat more of her dainties than I honestly required.

"And she'd welcome me, as Peter, with an amiable smile,

And sometimes she would talk to me, as Peter, for a while;

And finally she suffered me, as Peter, to embrace

Her lovely little figure and her pretty little face.

"And, as Peter, I was very, very jubilant until

I retired from being Peter and assumed the role of Bill;

But I retained, as Billy, my voracity for such

Little dainties which, as Peter, I had relished very much.

"And, as Billy, I discovered the identical retreat

Where, as Peter, it had been my cherished habitude to eat;

And, as Billy, I was smitten with the charms of Lizzie Fay,

And, as Billy, I began to go and see her every day.

"And she'd welcome me, as Billy, with an amiable smile,

And sometimes she would talk to me, as Billy, for a while;

And finally she suffered me, as Billy, to embrace

Her lovely little figure and her pretty little face.

"And, as Billy, I was very, very jubilant until

I resumed the role of Peter and gave up the role of Bill;

But when, as Peter, I returned to Lizzie as of old,

I found that she'd become to me, as Peter, very cold.

"She said that our relations could no longer be the same,

That her heart it was another's, and that Billy was his name;

Then I saw that I, as Billy, had performed a traitor's part,

For I'd robbed myself, as Peter, of the darling of my heart.

"And, as Peter, I experienced a strong desire to kill

The man who had deceived me in the character of Bill;

And it's even more than likely that to kill him I'd have tried

If I hadn't had a horror of committing suicide.

"But in my agony, as Peter, at renouncing Lizzie Fay,

I presume that I, as Peter, must have fainted dead away,

For, as Peter, I have told you every blessed thing I know,

Till to me, as Peter, consciousness returned an hour ago.

"My name, I'll add, is Peter as you very likely know;

I am sure that it is Peter, for my mother told me so;

But it might as well be James, Augustus, Jonathan or Paul,

For to all intents and purposes I'm nobody at all."

-- PHIN

--Daily Examiner, November 20, 1887

Thayer's later self-deprecating critique of his own work not only devalued "Casey" but also dismissed any of the ballads he had written for the Examiner during the fall of 1887. But several facts suggest that next to "Casey at the Bat," the "Strange Romance" would later gain not only the esteem of its author but also that of a wider audience. In 1892, when DeWolf Hopper and Thayer finally met at the Worcester Club, Thayer granted Hopper the unrestricted rights to continue to perform "Casey," and further gifted him with a copy of a ballad which Thayer would later perform in public as "The Detective." Assuming that Thayer intended for Hopper to perform the ballad in public, and knowing that Hopper in fact did perform the ballad in front of an audience on at least one occasion, we can deduce that both men realized the dramatic appeal of the story of the strangely divided detective. The Chicago Inter-Ocean in a brief review of an 1894 recitation by Hopper considered the ballad "worthy of a W.S. Gilbert." [1]

[1] The Inter Ocean 18 February 1894, p. 26. Thayer admitted that his 1887 ballads were consciously patterned on W. S. Gilbert's Bab Ballads, published in various editions from 1872 to 1898.

#CaseyattheBat #ErnestThayer #TwilightZone #SanFrancisco #SanFranciscoHistory #19thCenturyPoets #AmericanPoets #poetry #BlackstoneValley #RodSerling

Foggy night in a park in San Francisco. Haunted by the strange and violent occurrences of the city's free-wheeling Gilded Age, San Francisco now offers a variety of "ghost tours." Thayer's own encounters with the bizarre would find a place in his columns in the fall of 1887, including the ballad of "The Strange Romance of a Bold but Unfortunate Detective."

Lloyd Lewis and Henry Justin Smith wrote in their biography of Oscar Wilde that "Tales of superstition {in 1882, when Wilde arrived in America for a tour} were almost as common in the America through which Wilde was passing as they were in his native Ireland. In only one department was the West lacking: it had strangely few ghost stories. On the great open plains and in its sunburned cities, ghosts did not walk as they walked back in the dark woods and swamps of the East and South....The West might believe preposterous things about dead men, but if the dead were resurrected they had simply escaped death: that was all; there were no ghosts." Oscar Wilde Discovers America: 1882 (New York: Harcourt Brace and Company, 1936) p.269. Judging from the number of ''ghost tours" now offered nightly in San Francisco, including areas of Chinatown, Alcatraz, and Fort Mason, San Francisco had begun even in the 1880's to assemble its own congregation of restless spirits. Wilde himself may have offered an explanation, in The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), "It is an odd thing, but everyone who disappears is said to be seen in San Francisco. It must be a delightful city, and possess all the attractions of the next world."

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.