131 Years of Worcester's "Casey at the Bat" 1888-2019

@tgsports @RedSox @PawSox @telegramdotcom @BaseballBrit @NE_Baseball @baseballhall @OnlyAGameNPR @klgiven @BBHistoryDaily @Worcester_PL @TweetWorcester #CaseyattheBat #RedSox #PawSox

As Worcester enters a new era as a baseball mecca, the future home of the Triple-A affiliate of the Boston Red Sox, let's celebrate the city now known as the birthplace of the immortal "Casey at the Bat." It was thirteen decades ago, in August of 1888, during a break in the "baseball night" performance of a comic opera by Johann Strauss, that the impressive (6'5", 235 pound) DeWolf Hopper stepped into the spotlight at Wallack's Theatre in New York and assumed an elocutionary pose. Earlier that day, promoter "Colonel" John McCaull had given Hopper a clipping from the June 3 San Francisco Examiner, a 13-stanza poem entitled "Casey at the Bat." In later life, Hopper claimed that he would repeat that dramatic recitation over 10,000 times during his career. "Casey" became an instant hit, with men standing on their seats to cheer."It was one of the wildest scenes ever seen in a theater and showed the popularity of Hopper and of baseball,"[1] wrote the New York World reporter.

Wallack's Theater, Broadway, 1880's

In the 20th century, two cities contended for what Thayer would have termed the "doubtful honor" of having been the true location of the fictional Mudville. Stockton, California staked its claim on the basis of geography (the "mountain" and the "flat" referred to in the ballad, and Stockton players "Cooney" and "Flynn," who appear in the poem) and on the fact that Thayer, as baseball reporter for the Examiner, would likely have attended games there in 1886 and '87. Holliston, Massachusetts asserted an equally convincing case for its historic Mudville neighborhood--home to Irish immigrants from the 1840's--citing as evidence the presence of a local mill once owned by one of Thayer's uncles.

In December 1892 at the Worcester Club, Hopper and Thayer met for the first time. Following a convivial dinner, Thayer granted Hopper the unrestricted rights to perform "Casey at the Bat."

But no city ever had a better claim to "Casey's" immortality than Worcester. On the night of August 14, 1888 as DeWolf Hopper performed "Casey" for the first time on Broadway, Thayer quietly celebrated his 25th birthday at the family home on Crown Hill (the actual house at 67 Chatham Street has since been demolished). The timeline of Thayer's whereabouts early in 1888 shows him returning to Worcester from San Francisco (via Washington, D.C., where in February he helped Hearst and the Examiner staff promote San Francisco as a site for the Democratic presidential convention to be held that summer). Ernest would have arrived in Worcester just prior to the Great Blizzard which buried the East Coast from March 11 to the 14th. in the following weeks as New England dug out from the massive storm Thayer would have had plenty of leisure to consider his next submission to the Examiner, to scan his well-stocked library of high school and college books, and to ponder the perfect template on which to base his modern epic.

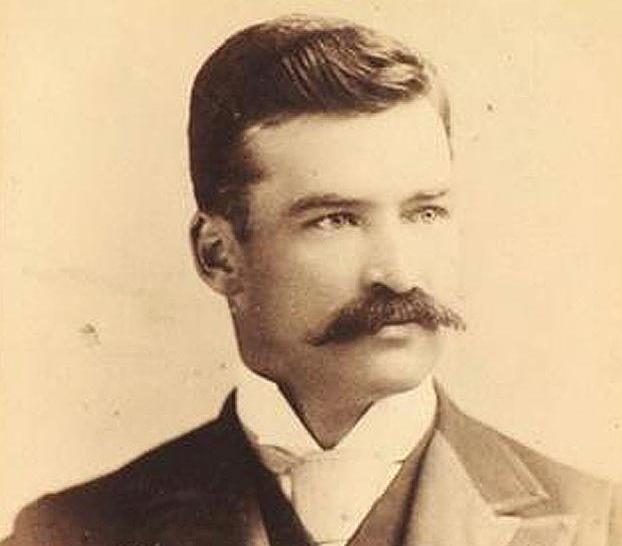

Mike "King" Kelly (1857-1894), star player of the Gilded Age

For "Casey" had not sprung fully-grown from Thayer's imagination. Mike "King" Kelly, a star for the Boston Beaneaters at the time "Casey" was written, was a possible real-life candidate for the Mudville slugger. Sold for $10,000 in 1886 to Boston by Chicago White Sox owner Al Spalding, the "$10,000 Beauty" published his autobiography in 1888 with the ghost-writing of Boston's baseball writer John "Jack" Drohan. Kelly even began reciting "Casey at the Bat" on vaudeville stages, and though Thayer would later accuse him of claiming "Casey's" authorship, there is no evidence that Kelly himself made such an assertion.

In fact, Thayer himself in later years would cite two possible models for his protagonist. Often, when interviewed about the origins of the poem, he would name his boyhood pal and Harvard classmate Samuel Ellsworth Winslow (1862-1940). "A born leader" as characterized by Thayer, Winslow had captained the 1885 Harvard nine to an unmatched 27-1 record, defeating Yale twice and claiming the championship of the Intercollegiate Base Ball Association. Though he plausibly opened the door to Thayer's lifelong fascination with baseball, Worcester's Winslow was an unlikely prototype for the doomed Mudville batsman. (See "Sam Winslow," Caseyatthe.blog January 31, 2019).

Samuel Ellsworth Winslow, Harvard Class of 1885 (1862-1940)

Until much later in life, Thayer's explanations of the origins of his ballad were remarkably self-deprecating. "It was my business to write," he often said, "and I needed the money." But in 1930 in response to a question from the Syracuse Post-Standard, Thayer mentioned a "Daniel Casey," an actual classmate at the Classical and English High School. Thayer confessed that he had "gagged" his fellow student quite deliberately with a fictional interrogation about "Cicero's third book of Virgil"-- a deliberate provocation because there was no such book. Confronted by the victim of his satire, Thayer belatedly realized, in Daniel Casey's towering presence, that he had gone too far. A strategic withdrawal on Thayer's part ended the standoff. But the episode, and the emotions it evoked, never entirely disappeared from consciousness. Decades later, Thayer had voluntarily opened this window into a childhood memory, suggesting one plausible source of "Casey's" name--though classmate Daniel Casey was not a baseball player.

But Thayer's own subtitle for the poem--"A Ballad of the Republic"-- suggested that "Casey" was always about more than baseball. As the foremost interpreter and promoter of "Casey at the Bat" through the 1930's, DeWolf Hopper understood that "There is no day in the playing season that this same supreme tragedy, as stark as Aristophanes for the moment, does not befall on some field."[2]

Hopper was on the right track, even though Aristophanes was a comic, not tragic, dramatist. The actor knew intuitively on his first reading that "Casey" had roots not only in the epic literature of the 19th century, but also in the ancient past. To some in the audience at Wallack's Theatre that August night in 1888 (including Major General William T. Sherman) the cadences of the baseball epic bore an uncanny similarity to a much-recited ballad popular both in Britain and America since 1842. That forerunner was Thomas Macaulay's "Horatius," or "Horatius at the Bridge," as the poem became known to American schoolchildren, recounting the heroic defense of the Tiber bridge in 509 BC against the mighty armies of Etruscan overlord Lars Porsena. Macaulay's 70-stanza ballad reformatted for the British empire this tale told by ancient historians of the foundation of the Roman Republic.

Publius Horatius Cocles leads the Romans in battle against the Etruscans, by Tommaso Minardi (1787-1871)

Publius Horatius Cocles leads the Romans in battle against the Etruscans, by Tommaso Minardi (1787-1871)

Ultimately, Worcester's most important contribution to Thayer's masterpiece was the classical education the city had provided its native son. Thayer in his witty, irreverent way, had taken the ancient legend of the defense of the Roman bridge and turned it on its head (and in the process had written a far better poem than Macaulay's "Horatius"). We can now understand "Casey" as a "creative misreading" of Macaulay's popular heroic ballad. "Casey's" 20th-century readers were so enthralled by the drama enacted on the baseball field that they missed what Thayer's classmates and contemporaries clearly grasped: Thayer was teaching America the wisdom of the Greeks. For unlike the Romans (or their American counterparts of the 19th century), the Greeks understood the ennobling value of tragedy--their highest form of drama.

Bill Ballou (Worcester Telegram & Gazette, March 30, 2019) has made a compelling case for the simplicity of a traditional name--"Worcester Red Sox"--for the relocating team. While this is the obvious choice, the city would have to accept an inevitable contraction of the name to "Woo Sox," just as the Pawtucket Red Sox became the "Paw Sox." In the meantime, many expansion or relocation teams find that a public naming contest generates a great deal of civic pride and historic interest. Ballou has put forward the alternatives of the Worcester Caseys, or the Mighty Caseys--both worthy considerations given the connection with hometown scholar Ernest Thayer.

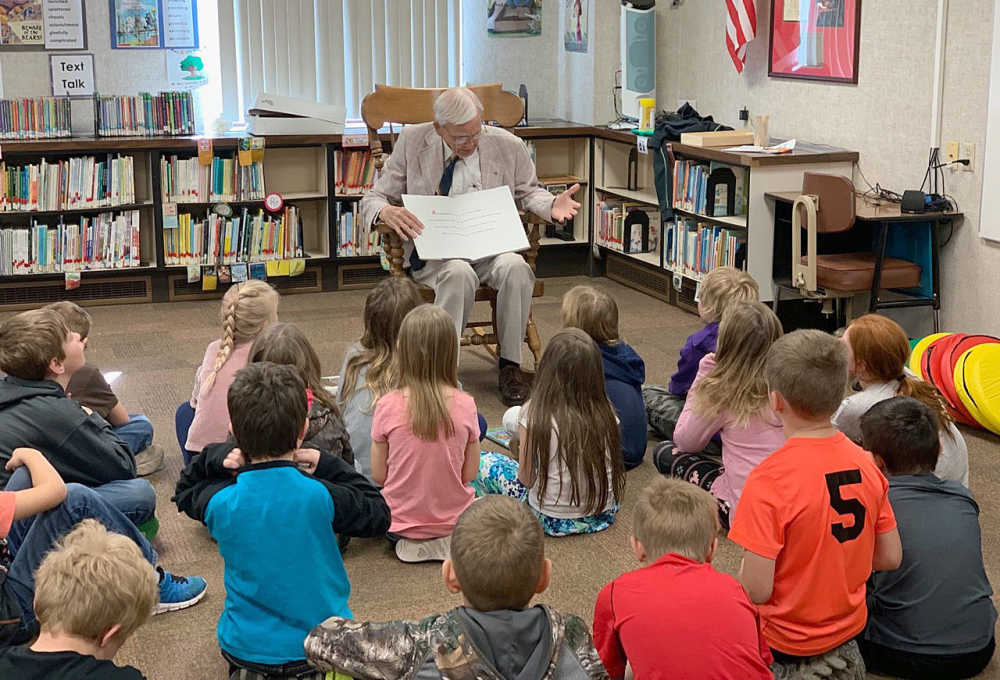

Whatever the choice of name, the Worcester team--and community--will have multiple opportunities each season to embrace the local connection to the epic of an American folk hero. Casey emerged from a ballad which for 13 decades has "lurked alive at the edges of American consciousness" in the words of Poet Laureate Donald Hall. Consider the educational and entertainment possibilities for an August 14 celebration of Thayer's birthday, juxtaposed with that memorable first performance of the poem by DeWolf Hopper on the same date in 1888. And celebrate also the virtues of public education and the lessons of the classics--for as Hopper correctly perceived, Casey had deep roots as a classical hero of the tragic variety. Sports teaches its lessons by loss as well as victory, for as the Greeks knew, sorrow can also teach wisdom. In a memorable epigram in his chronicle of American baseball from its earliest times, star player of the 1870's and sporting goods entrepreneur Albert Spalding wrote:

Love has its sonnets galore. War has its epics in heroic verse; tragedy its somber story in measured tones. Baseball has Casey at the Bat.

[1] New York World, 15 August 1888, quoted in John Evangelist Walsh, The Night Casey Was Born: The True Story Behind the Great American Ballad "Casey at the Bat" (New York: The Overland Press, 2012), p. 132.

[2] DeWolf Hopper, Reminiscences of DeWolf Hopper (New York: Garden City Publishing Company, Inc., 1927), p. 93.

Cover photo for this article:

Classical and English High School, Elm Street, Worcester, designed by H. H. Richardson and opened in 1871. Both Ernest and his sister Nellie attended classes here (Ernest graduated in 1881). Boys and girls, both black and white, attended the school. The building has been demolished. (Courtesy Yvette Porter Moore, yvetteportermoore.com, "A Breath in Time: Honoring the Lives of Our Ancestors").

1 comment

Wonderful site! Thanks for posting these fascinating facts and insights.

Arthur Powers

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.