National Poetry Month and "Casey at the Bat" -- Part One

From the Wilson (North Carolina) Times last week (April 12, 2019) came a thoughtful, quietly impassioned column by Sanda Baucom Hight, "Celebrate National Poetry Month: Poetry is not finished."

"Poetry is everywhere," wrote Sanda Hight. "From nursery rhymes, simple jingles, song lyrics, biblical Psalms, poems of popular culture and works of the world’s greatest poets, poetry touches the lives of all of us in one way or another." So I reminded 5th graders when they contested our April focus on poetry: that they were already deeply immersed in poetry in their daily lives--in the poetry of popular music that they sang every day on the playground. Ms Hight makes the strong case for teaching poetry in schools--something my family fondly recalls from our own childhoods. Two poems she suggests to "hook" children on poetry are Robert Frost's "The Road Not Taken," and (of course, or you would not be reading this piece), Ernest Lawrence Thayer's "Casey at the Bat." Or, as the 5th graders reminded me, "Dr. Seuss!"

One of the functions of our classroom poetry hours was to introduce the way that poetry stretches our minds. Poetry awakens an appreciation for layers of subtlety and ambiguity in our thoughts and dreams. A good poem leaves us with a sense that our world has grown, even in a small way. The best poems in our literature can overturn our preconceived notions about the world and our place in it--and poems do this in ways we can learn to appreciate, whether on our own or in the classroom.

"The Road Not Taken," photograph courtesy of Norwegian Digital Learning Arena

"The Road Not Taken," for example, is anything but a simple poem. David Orr, poetry critic for the New York Times, has written a brilliant and very readable book on "The Road Not Taken," subtitled "Finding America in the Poem Everyone Loves and Almost Everyone Gets Wrong". Frost, it seems, took a sly delight in poetic subtlety and even misdirection. But clues to a wiser reading of "The Road Not Taken" are there in plain sight--for example, the narrator's memory of how both roads "... that morning equally lay / In leaves no step had trodden black." Get David Orr's book and read it -- you'll thank me later!

And neither is "Casey at the Bat" a simple poem. One of its beauties is the multiple levels at which the ballad can be enjoyed. In its most widely known sense, "Casey" is America's best, and best-known, "baseball poem." Yes, it is about America's uniquely national game, with a dramatic twist with which every baseball fan in any era would be familiar. But the poem's language, and its literary antecedents, always suggested that the poem was about more than baseball. The Oxford Book of American Poetry (2006) classifies "Casey" both as "a mock-epic" and also as "a critique of hero-worship." Both characterizations are true in very specific ways. As a critique of hero worship, "Casey" dramatizes the perils of vesting any single player, however heroic, with one's personal dreams and aspirations (as we did with our sports heroes as children), or likewise the dangers of yoking civic pride, identity, and communal well-being with the fortunes of the local Nine, as did poor Mudville.

As a mock-epic, Casey referenced a very specific epic, so much so that the poem actually became a parody--or in an even more descriptive term, revived from Elizabethan usage by Yale Professor Harold Bloom, a misprision (a creative misreading) of the ballad "Horatius." Penned by British historian and parliamentarian Thomas Macaulay, the ballad published in 1842 became known in America as "Horatius at the Bridge" for its dramatic setting at the Sublician Bridge across the Tiber.

Engraving of Horatius in battle by Hendrik Goltzius, 1586

It was here, on the western approach to the bridge in 510 BC, that the Roman captain of the guard, Horatius "Cocles" (One-Eye) stood to defy the might of the Etruscan army led by overlord Lars Porsena. Flanked by two sturdy wingmen, Horatius confronted the Etruscans at the narrow approach to the Sublician Bridge while his countrymen chopped away at the wooden pilings and abutments behind him. In three vicious rounds of single combat (in Macaulay's version), Horatius and his companions held back the Etruscan vanguard long enough for the Romans to drop the bridge into the Tiber and to preserve their infant Republic. This was a legend which would resonate far across the centuries to inspire American colonists challenging the might of the British empire in the 18th century, and to embolden Winston Churchill and his countrymen defying the Luftwaffe and Wehrmacht in the 20th.

Churchill memorized the 70 stanzas of Macaulay's "Horatius" as a schoolboy at Harrow. He would later draw on the example of Horatius to inspire the British as they defied the threat of Nazi invasion.

Macaulay, in turn, had taken his inspiration from the Roman historian Livy, writing in the Augustan age about the long-ago Roman Republic. Macaulay endeavored to recreate the ancient ballads which the scholars of his day believed had been the source of stories recorded by Livy and other later historians of Rome's earliest days. "I amused myself," wrote Macaulay, "...with trying to restore some of these long perished poems." Macaulay went so far as to place his collection of ballads in historic context, each with an introduction explaining how notional minstrels or balladeers might have regarded the heroic episodes of a distant past.

From the Renaissance through the 19th century, artists interpreted Horatius' defense of the bridge in various ways. In this version of the legend by Francesco Pesellino (1422-1457), Horatius appears on horseback. On his white steed, in this "time-lapse" conflation of events, he both defends the approach to the bridge and escapes across the Tiber from the arrows of Tuscan archers.

Macaulay's subtitle to "Horatius," the first of his Lays of Ancient Rome (published in 1842), places his fictional ballad in a precise historic context: "A Lay Made About the Year of the City CCCLX." (A lay, of course, is "a ballad meant to be sung or recited." The most ancient of epics, the Iliad, begins as a song: "Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles son of Peleus, that brought countless ills upon the Achaeans...") The Romans dated their history from the mythical founding of Rome by Romulus in 753 BC, therefore, the anno urbis conditae, or Year of the City to which Macaulay dated his ballad, is 753 minus 360, or 393 BC--117 years after the battle at the Sublician Bridge is supposed to have occurred in about 510 BC. Macaulay's balladeer sings a story "looking back" from a post-heroic age to the glories of Rome's infant Republic -- much as if Thayer had been writing a ballad about the preliminary chapters of the American Revolution.

The hut of Romulus, the founder of Rome, was preserved as a shrine on Rome's Palatine Hill up through the 4th century AD. The Romans dated the founding of their city very precisely, to April 21 in the year 753 BC. Courtesy Roma Segreta (www.romasegreta.it April 20, 2013).

Why the insistence on a precise date? Macaulay was obviously entranced with his own notion of re-creating the ancient sources of Roman ballads: but whether in jest or imitation, Thayer likewise placed his own ballad in an exact year. Thayer's subtitle "A Ballad of the Republic, Sung in the Year 1888" is the clearest hint we have that he intended to trace the ballad of "Casey" on Macaulay's epic template.

We'll return to the legend of "Horatius" in later blog posts because it is fundamental to the way 19th century readers understood "Casey at the Bat." But for the moment, it's enough to note that Thayer's choice of the "Horatius" legend as a prototype for his ballad of "Casey" was no mere whim.

Finally, the challenge to heroism in a post-heroic age was a theme that Thayer had mined ever since college days as the editor of the Harvard Lampoon. Before graduation from Harvard, Thayer had been chosen (as had his brother Albert ten years earlier) to give the "Ivy Oration" on Class Day, June 19, 1885. Thayer encapsulated his chosen theme in one memorable line: "There is no chance in Cambridge for a young man of heroic intentions." Thayer's droll oration was built around a fantasy of rescuing damsels in distress, for which (he said) there was no need in quiet Cambridge--"It is old, it is quiet, it is slow," said Thayer, "...eminently fitted for a university town:"

"There is no place in Cambridge for a young man of heroic intentions...it is old, it is quiet, it is slow, eminently fitted for a university town," said Thayer in 1885. The photo is of Memorial Hall, completed in 1877 to honor Harvard's Civil War dead. Thayer and his classmates, born during the War but too young to remember it, felt overshadowed by the War's legacy

Thayer's nostalgia for a bygone heroic era amused the Ivy Day audience in Harvard Yard and readers in his home town of Worcester, where his discourse was reprinted in the local paper. But in asserting that there was "no place in Cambridge for a young man of heroic intentions," as in other youthful jests, Thayer was wrong. There was in fact a place in Cambridge for the young man with heroic intentions: a place where glory could be won; where heroes were raised to the heights of human endeavor or cast to the depths; where the heroic virtues of courage, temperance, and persistence were exercised and extolled; and where mortals might re-enact the rituals of victory and defeat that had inspired young men since the time of the first Olympians. That place was known as Holmes' Field.

Holmes Field (undated), looking southeast, ca 1890. The Memorial Hall Tower can be seen at far left.

Here upon the coarse grasses of the former Holmes estate contended the football and baseball teams of the era. And into the storied saga of Harvard athletics, and into the adversity of Harvard-Yale competition of the 1880's, strode a new kind of hero, clad in a baggy flannel uniform, carrying a bat and glove. Among this band of heroes one young man stands out--a charismatic leader, fiercely competitive player, and brilliant coaching strategist named Samuel Ellsworth Winslow. You can read more about Winslow here!

Illustration for Edgar Allen Poe's "The Raven," (1845) by John Tenniel. A handful of 19th-century American poems dominate current Google searches

Illustration for Edgar Allen Poe's "The Raven," (1845) by John Tenniel. A handful of 19th-century American poems dominate current Google searches

Eclipsed in current Google SERPs (Search Engine Results Pages) only by Whitman's "Song of Myself," and Edgar Allen Poe's "The Raven," "Casey at the Bat" holds its ground as one of a handful of American verses (including Clement Clarke Moore's "A Visit From Saint Nicholas" which maintains special preeminence) to demonstrate continued popularity from the 19th century to the 21st. I suggest that the reason for "Casey's" remarkable longevity is rooted deep in the legends and literature of the past. Ernest Thayer acknowledged a poetic debt to his contemporary W. S. Gilbert, comic balladeer and librettist of Gilbert & Sullivan fame. But we'll also explore links in Thayer's "Casey" to Alexander Pope, Bayard Taylor, and even to the Bard himself--William Shakespeare. And what did Thayer believe his "Ballad of the Republic" had to say either about, or to, the Republic of his era? We'll explore those possibilities also in future posts.

Etruscan bronze warrior (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

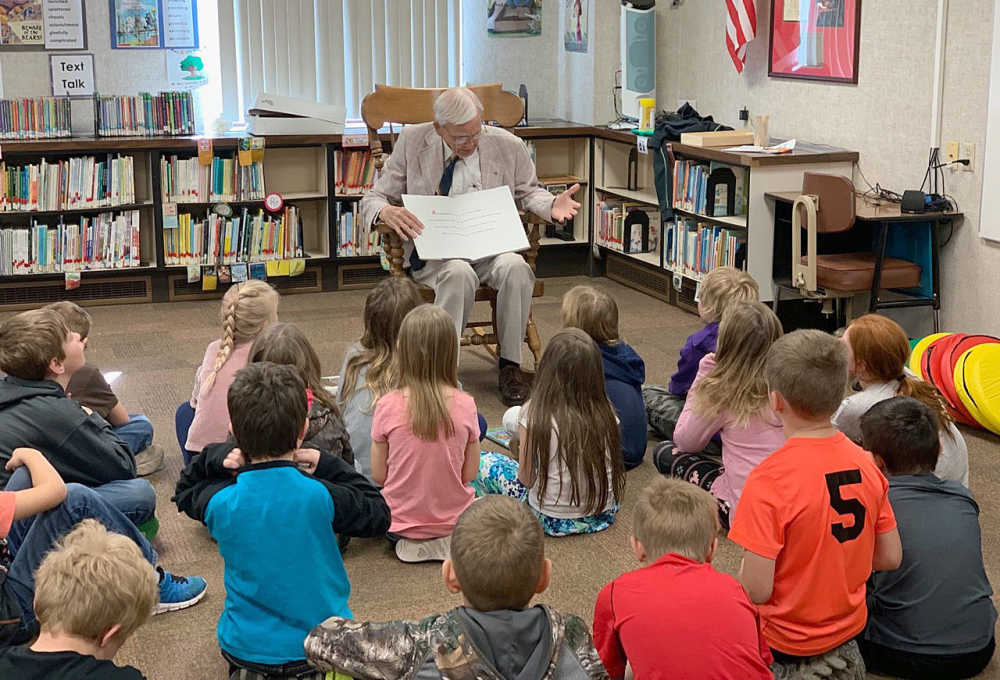

Cover Photo Credit: Daily Reporter (Spencer, Iowa), April 21, 2019. Community member Bob Rose reads "Casey at the Bat" to second graders at Fairview Elementary.

@TheWilsonTimes @MartinKessler91 @klgiven @OnlyAGameNPR @SantaBarbaraHistoryMuseum @worcestermag @tgsports @BaseballBrit @POETSorg @poetrymagazine @PoetryFound @Jeremy13News @Worcester_PL @NE_Baseball @BBHistoryDaily @BallgamedPod @Ed_Achorn @Jim_Ingraham @CommonTalkPod @radio_worcester @sabr @AnnKillion @TourBlackstone #PoetryMonth #BlackstoneValleyRI #CaseyattheBat

Illustration for Edgar Allen Poe's "The Raven," (1845) by John Tenniel. A handful of 19th-century American poems dominate current Google searches

Illustration for Edgar Allen Poe's "The Raven," (1845) by John Tenniel. A handful of 19th-century American poems dominate current Google searches

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.