The former Mudville nine

faced likely loss upon that date,

(they’d moved from Mudville years before —

it was best to relocate).

With Cooney-Barrows out one-two,

in the ninth, down five to three,

a tiny one-point-two-five was

their win expectancy.

A few fans sprung up from their seats,

to beat the traffic’s rush.

That trickle turned into a stream,

a surging human crush.

But some still there remembered Casey,

standing in the hole,

and thought “With his fly ball rate,

he could knock one past the pole.”

But Flynn hits before Casey,

as does speedy Jimmy Blake;

Flynn’s OPS was in the tank,

and Blake could hardly rake.

So on those few still hopeful fans

a heavy feeling sat;

Casey’s odds were dim indeed

of getting an at-bat.

But Flynn held off the breaking stuff,

and drew a stunning walk;

while Blake, the leadoff man, saw his

weak grounder strike a rock.

And when the play was finally done,

the bad hop had shot through —

the men who stood on base and smiled

added up to two.

Then the speakers rose to life,

HD screens said “Make some noise!”

A hopeful cheer sprung up anew

from all the girls and boys.

It started as the fans began

to hope for a blown save,

and it wrapped around the bleachers twice,

travelling like the wave.

There was ease in Casey’s stride as

they played his walk-up song.

There was confidence throughout the stands

he’d hit a three-run dong.

And when, while taking in the noise,

Casey tipped his cap,

you felt no doubt he’d knock one out,

a mighty towering rap.

Five thousand cellphones held up

for his practice cut.

The phones stayed on, recording all,

as his foot dug in a rut.

Then while the leveraged closer prayed

that he could slam the door,

Casey knew he’d boost his slash line,

while augmenting his WAR.

And now the pitch comes spiralling

with lofty rate of spin,

and now he stands there mute, inert,

watching it come in.

Close by the black at the plate’s edge,

the sphere slides just aways,

“Not my spot,” says Casey.

“Strike one!” the umpire says.

From the benches, filled with people,

flew up a slew of fists and beers

for what (hashtag)TeamCasey dubbed

the worst call of the year.

“Check the friggin’ QuesTec!”

roared a raucous older fan —

a decade-obsolete request

(the system’s now TrackMan).

With a toothy grin and bearded chin,

great Casey’s visage shone;

he quieted the maddened crowd,

he’d face the pitch alone.

He stepped back in another time,

the closer hurled once more,

and with no swing he watched a cutter

catch on the backdoor.

The umpire called “Strike Two!”

and what the fans say is deleted;

it leaves the back end of a bull,

but it shall not be repeated.

Now Casey’s face grew stern and cold,

his muscles strained and flexed,

and despite a friendly pitcher’s count,

the closer sure was vexed.

The sneer is gone from Casey’s lip,

his bat held at a dangle,

his thoughts alight on nothing but

the optimal launch angle.

And now the pitcher holds the ball,

and now he lets it go,

and now the air is shattered by

the force of Casey’s blow!

Oh, somewhere in this modern land

the sun shines much too bright.

But a podcast’s streaming somewhere

as the wi-fi signal’s right,

somewhere someone’s blogging,

someone’s laughing at a GIF.

But there is no joy for Casey’s fans —

he hit into the shift.

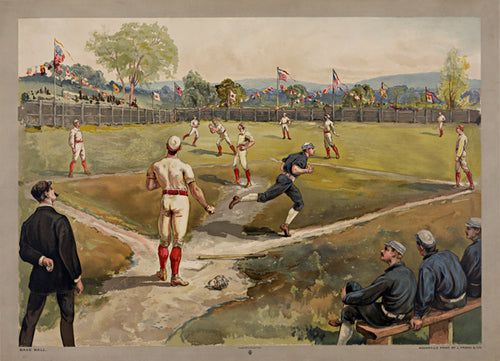

Contributions by Brandon Lee and Darius Austin. Art by Ken Maeda.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.