Casey at the Sabermetric Bat

Fantastic piece of analysis of the circumstances of Casey's famous at-bat by Leigh Allan from SBNation! And have you ever wondered why the opposing manager chose to pitch to Casey, when first base was open.....?

Even with all the analysis being done in baseball these days, much to great benefit and some to great detriment, it appears that one aspect of the game has been sadly overlooked: Baseball poetry.

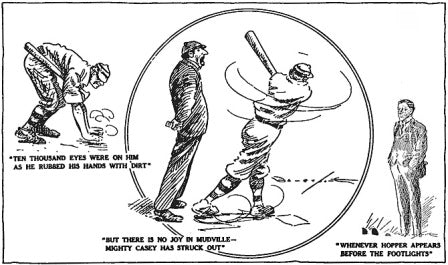

Well, actually, baseball poem, since there’s only one that matters, “Casey at the Bat” by Ernest Lawrence Thayer. Thayer was a bit of a one-hit wonder, a Philip Humber of American poetry, a respectable humor columnist without any other claim to fame. Still, 22 other pitchers have thrown perfect games; nobody has ever come close to penning another great baseball poem.

“Casey” has survived 131 years without being torn apart by analysis, so it’s about time to ruin your enjoyment, just as launch angle obsession and the strikeouts-by-the-dozens-and-occasional-homer strategy it is causing are ruining the enjoyment of baseball itself. Don’t fret — this isn’t poetry analysis like you got stuck doing in high school, with all the iambs and anapests and symbolism and metaphors and other big words. It’s baseball analysis, way overdue.

Why overdue? Because poetry often has insightful observations, worthy of attention because they can guide us on a proper path, that’s why. Yeesh.

You know how the stage is set. Mudville’s down 4-2, bottom of the ninth, so the outlook wasn’t brilliant for the Mudville nine that day. No mention whether the opponent had a good closer, but that wasn’t likely in 1888.

Things got worse when Cooney died at first and Barrow did the same. Not only two outs, but the pitcher’s GB% is 100. Melancholy set in for the crowd, especially because of who was coming up — Flynn and Blake. Yuck.

This makes you wonder about the Mudville manager. Why are Flynn and Blake hitting in front of Mighty Casey? Casey must have been hitting third or fourth, so they were the top of the order. Who puts guys like that at the top of the order? Doesn’t he know the best place to bat your best hitter is the No. 2 slot? No wonder they only had two runs.

Flynn came to the plate, a player described by Thayer as either a “lulu” or a “hoodoo” — he changed things around through the years. We may call something “a real lulu” in a positive sense these days, but back then “lulu” was no compliment. Worse yet, a hoodoo was a jinx.ill, Flynn comes through, letting drive a single. That meant an ISO of .000 for the at-bat. That wasn’t going to help him any come arbitration — but it did extend the game.

Next is Jimmy Blake, called a “cake.” Thayer sometimes changed it to “fake.” Not a compliment, either way. Blake’s up, Mighty Casey on deck, and things get interesting:

And Blake, the much despised, tore the cover off the ball

And when the dust had lifted, and men saw what had occurred,

There was Jimmy safe at second and Flynn a-hugging third.

Now, that’s action. Interesting action. Fun for the fans.

Why is Flynn a-hugging third? Sure, good baserunning meant taking no chances trying to score, since his run didn’t matter on its own. But “a-hugging” suggests he was sliding in, as does “dust had lifted.” No reason for that unless a throw is coming to third — a terrible mistake by the opposition.

Notice Thayer doesn’t say Blake hit a double, easily rhymed with “keeping out of trouble” or “putting Casey on the bubble.” Couple that with Flynn’s a-hugging, and the only possible interpretation is that when the outfielder screwed up and threw to third, Blake took second on the throw, putting the tying run in scoring position. What a terrific poetic lesson! And what excitement for the Mudville faithful!

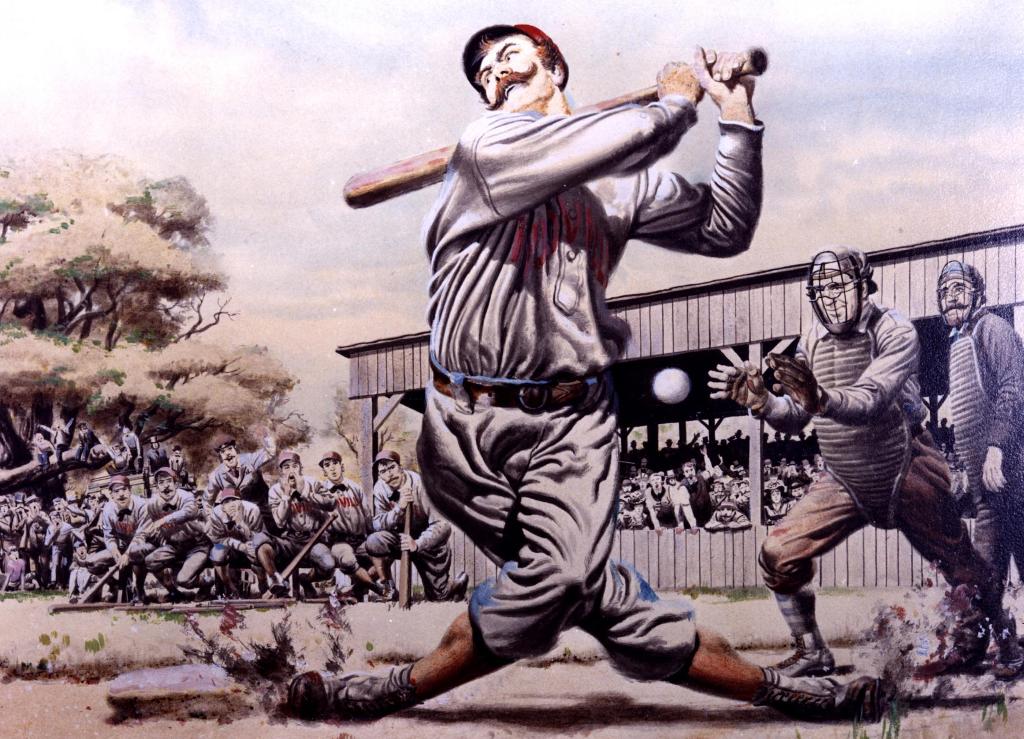

Which brings us to Casey. Mighty Casey. You know what happens now. Casey takes a strike, crowd gets ticked off, good sport Casey calms them down. Ditto on strike two, setting the stage for the big finale.

At this point, it should be noted that 1888 was the return year of the three-strike out — it had upped to four for a season, then changed back. So, if Casey wasn’t a quick learner, he may have been confused. Still.

You have to think that up 0-2, a waste pitch is called for. Ideal would have been a slider off the plate, but there was a danger of advancing the runners — plus the little problem that the slider wouldn’t be invented for another generation. So Casey didn’t have to worry about that. Other breaking balls existed, but pitchers had only been throwing overhand for four years, giving them little experience at that angle. Advantage, batter.

Now consider Mudville’s point of view. Tying runs in scoring position. Two outs, batter down 0-2. Every coach in the history of the game would tell Casey to shorten his swing and go the opposite way. The modern shift might not have been a thing then, but the second baseman had to shade toward the bag to keep Blake honest, leaving a gaping hole on the right side (Casey is always depicted as a righty).

Plus, there’s a reason baseball gloves are called “mitts.” In 1888, it looked like the fielders had snuck into their kitchens before the game and stolen their mom’s oven mitt. That made for a lot of ticked off moms and a lousy way to try to catch a ball. A big hitter like Casey should have been able to knock the mitt right off of a fielder’s hand.

But does Casey hit strategically? Of course not, because he’s a slugger and never bothered to learn how to actually bat. Remind you of any White Sox? Instead, Casey does the tooth-clenching bit, goes all violent pounding the plate, shatters air with the force of his blow. Whiff time, no bands playing, no light hearts, no men laughing, no children shouting, yada, yada.

Game lost for failure to play smart baseball, for being obsessed with dingers. So it was for one infamous at-bat 61 years before Bill James was even born, and for so many, many now.

And you didn’t think poets could see the future.

--By Leigh Allan, from SBNation www.southsidesox.com A Chicago White Sox Community

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.