“One swallow may not make a summer, but one poem makes a poet.”

I am reading now, with much pleasure, a manuscript by Richard Collins Davis titled Ballad of the Republic: Love, War, and Tragedy in Ernest Thayer’s “Casey at the Bat.” Mr. Davis is the proprietor of a splendid website devoted to Casey (https://caseyatthe.blog/blogs/caseyatthe-blog).

I made bold to suggest to Richard that George Whitefield D’Vys, one of several who claimed authorship of “Casey,” might bear further examination, as I had done rather a lot of work, eons ago, on this particular charlatan. Recently I came upon an essay about challengers to Ernest Lawrence Thayer in a 1923 book by Burton Egbert Stevenson, Famous Single Poems and the Controversies Which Have Raged Around Them. Pretty good, I thought, and thus share the essay below, in two parts.

From the book’s jacket: Oliver Wendell Holmes said: “I would rather risk for future fame upon one lyric than upon ten volumes.”

This book contains fifteen such famous “lyrics,” and tells how they were written and of the controversies waged about their authorship. It tells of “Kaiser & Co.,” which achieved fame as an international incident when an American Navy officer recited it at a Union League Club dinner after the Spanish War; “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” whose author thought he would be remembered as the compiler of a Hebrew lexicon; and other stories equally strange and romantic. [“Casey at the Bat” is not the least of these; now for Burton Stevenson’s essay.]

Mention has been made of the comfortable and consoling theory held by many optimists that every great work of art possesses an immortal soul which ensures its survival through the ages, and that consequently nothing which has passed from human ken is worth lamenting, since the very fact that it died proves that it was not immortal, and therefore not a masterpiece. Francis W. Halsey, in Our Literary Deluge, stated this theory with much eloquence:

We may be absolutely certain that whatever is good will not die. Wherever exists a book that adds to our wisdom, that consoles our thought, it cannot perish. Nothing is so immortal as mere words, once they have been spoken fitly or divinely. A good book die! We shall sooner see the forests cut away from the hillside…

and so on.

Which is just empty rhetoric. Of course one cannot say definitely and finally that anything is lost so long as the world continues to support the human race, for there is always a possibility of finding it. Perhaps another Vermeer may be discovered some day, or a statue by Praxiteles, or the Gospel of St. Matthew. But the chances are against it. And it is just as certain that modern literature is built upon a foundation of forgotten masterpieces as that modern life moves over an earth compounded of the forgotten dead.

Indeed, the survival of masterpieces, far from being due to any inherent quality, is largely the result of accident. A few statues catch the conqueror’s eye in the captured city and he carries them off — the rest are destroyed; the fleeing inmates snatch a few pictures from the walls of the burning house — the others go up in smoke; the anthologist chooses a few poems from among many to publish in his “Reliques” or “Pastorals,” and the others vanish into darkness. We can only hope that, in each case, the best ones were selected, but there is no way to prove it.

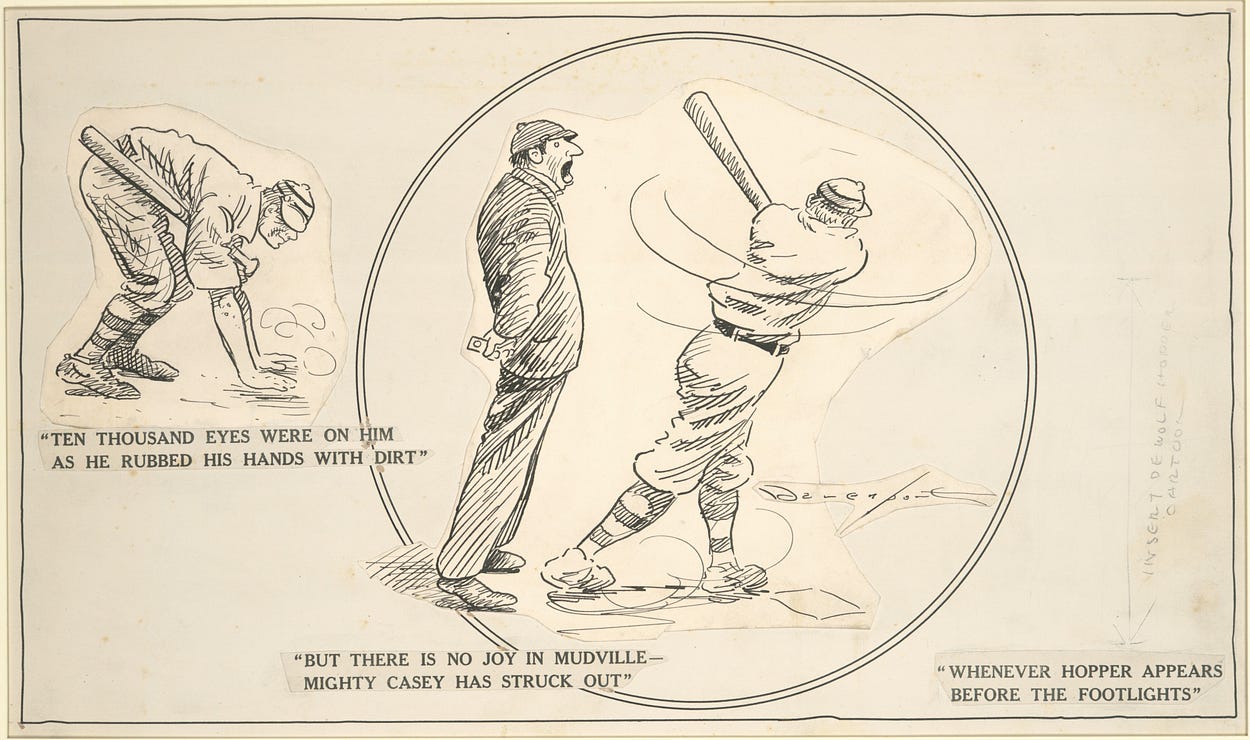

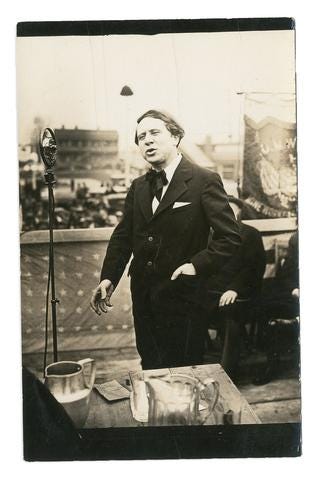

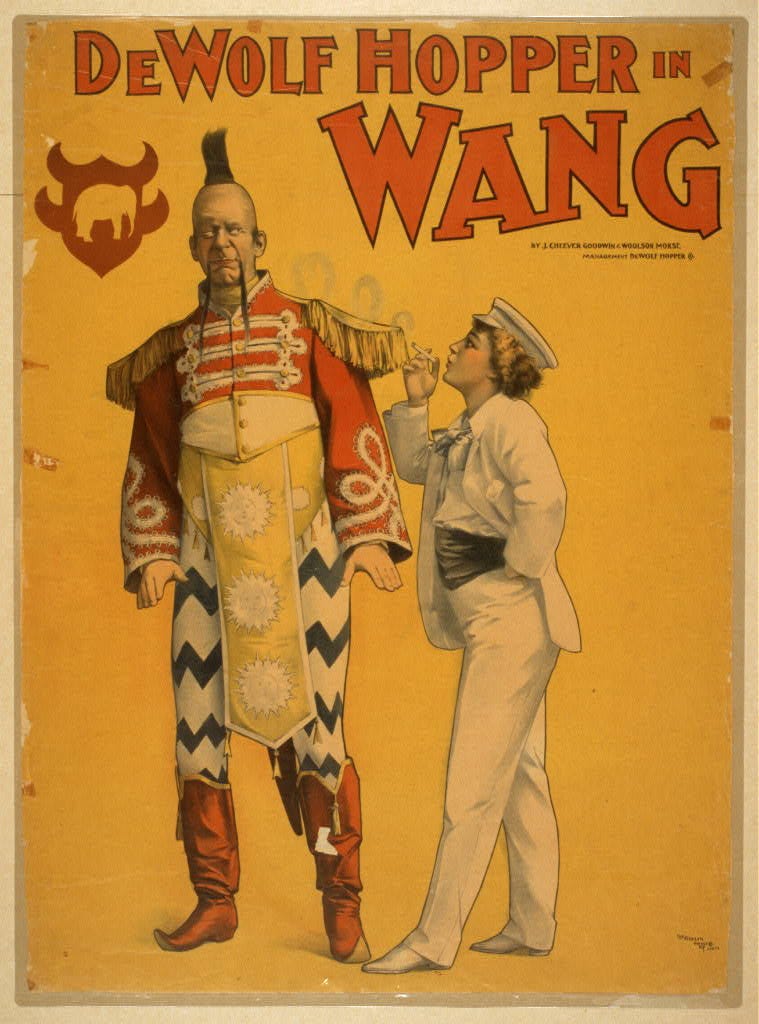

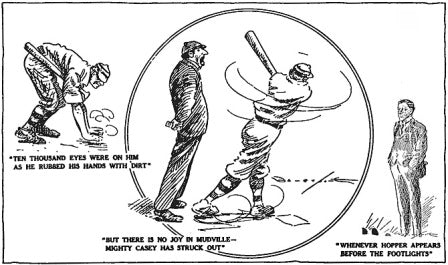

And even when a masterpiece does survive, it very often needs a press agent before it is generally recognized as such. It was Chaplain McCabe who advertised the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” by singing it in his incomparable voice, Captain Coghlan who called the world’s attention to “Hoch! der Kaiser” by reciting it at the psychological moment, and De Wolf Hopper who furnished the publicity which made a household word of “Casey at the Bat.”

And yet Mr. Hopper does not deserve the credit so much as Archibald Clavering Gunter, for it was the latter who discovered the poem in a newspaper, perceived its merits, and gave it to Mr. Hopper with the suggestion that he recite it. Now this was an extraordinary thing. It is easy enough to recognize a masterpiece after it has been carefully cleaned and beautifully framed and hung in a conspicuous place and certified by experts; but to stumble over it in a musty garret, covered with dust, to dig it out of a pile of junk and know it for a thing of beauty — only the true connoisseur can do that.

That is what Mr. Gunter did when he dug “Casey at the Bat” out of the smudgy columns of a newspaper more than thirty years ago. His novels have fallen into undeserved neglect, for some of them are rattling good yarns — who that met her will ever forget the beautiful flower-girl of the Jardin d’Acclimatation, with her white and red roses? At least let it be remembered that to him the American public owes its introduction to the supreme classic of baseball.

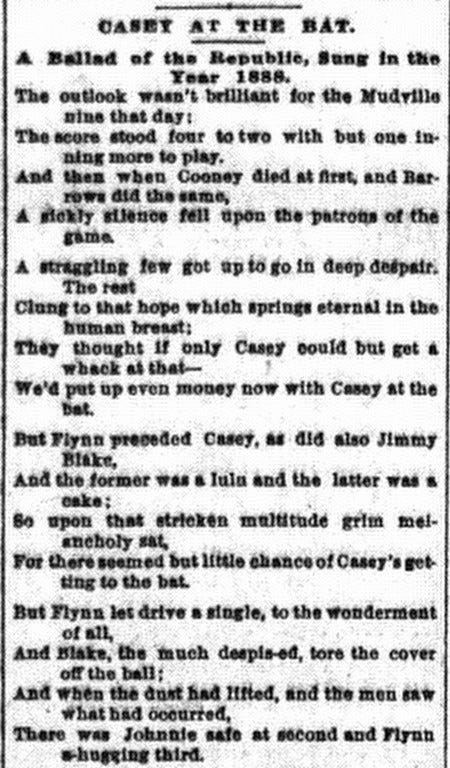

For everyone has now agreed that that is what “Casey” is. But classics have a way of being despised or ignored by their contemporaries, and when the poem first appeared in the San Francisco Examiner nobody hailed it with shouts of joy or suspected that the great Casey was to become immortal. In fact, the Examiner staff was rather proud that the New York Sun should think well enough of the poem to copy the last eight stanzas. The first five were remorselessly lopped off — but it has always been one of the inalienable rights of exchange editors to mutilate masterpieces, so nobody even thought of protesting, and it was in this acephalous form that Casey started on his travels through the east — a fact whose relevance will appear later on. Luckily it was in the Examiner and not in the Sun that Mr. Gunter saw it, so he got the complete poem. He cut it out and put it in his pocket and bided his time.

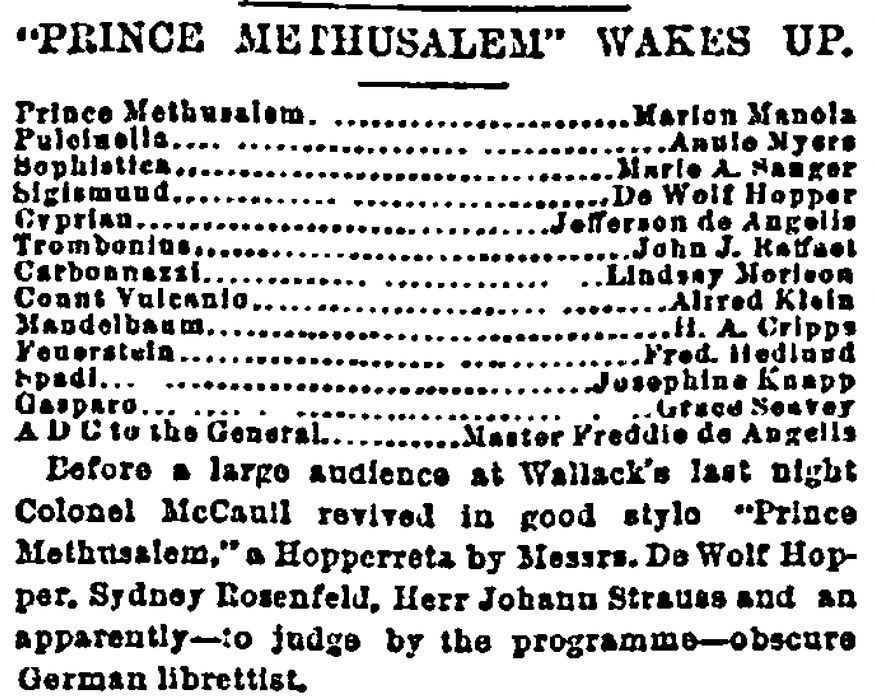

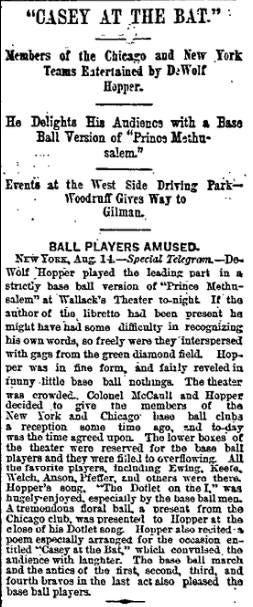

De Wolf Hopper was appearing at Wallack’s Theater in New York City in a comic opera called Prince Methusalem. He was not then the public institution he has since become, but just a rising young comedian for whom “Wang” had not yet been written. However, even then, he had a wide circle of acquaintances, of whom Mr. Gunter was one. It chanced that one morning, as he was looking over the paper, Mr. Gunter saw the announcement that the New York and Chicago baseball clubs were to be at Wallack’s that night as Mr. Hopper’s guests. He bethought him of “Casey at the Bat,” hunted up Mr. Hopper and gave it to him with the suggestion that he recite it. He added that it was a really great poem and was certain to

make a hit with the baseball people.

But the lengthy comedian regarded it with dismay, for it seemed to him even longer than himself. But when he read it over he saw its possibilities, pitched into it and mastered it in a couple of hours. He had no need to study its atmosphere, for he had always been a baseball fan himself and could visualize every line.

When the curtain went up that night the two teams, headed by Anson and Ewing, were in the boxes, and in the course of the show Mr. Hopper, as he puts it, “pulled Casey on them.” Anyone who has ever heard him recite it can imagine the effect. It brought down the house, and then and there took its place in his repertoire.

After the performance he hunted up Mr. Gunter and asked him who wrote “Casey,” for it seemed only fair that the author should have a share of the glory; but Mr. Gunter did not know. It was not until four or five years later, after Mr. Hopper had recited the poem during a performance of “Wang” at Worcester, Mass., that a note was sent in to him asking him to come around to a club and meet the author of “Casey.” Of course he went, and was introduced to Ernest L. Thayer. “Over the details of the wassail that followed,” says Mr. Hopper, “I will draw the veil of charity.”

Meanwhile, as is usually the case with famous fugitive poems, many claimants to the authorship had appeared, and some of them had even tried to compel Mr. Hopper to pay a royalty for the privilege of reciting it. The basis of most of these claims was exceedingly fantastic, but one man, at least, succeeded in building an elaborate structure of evidence in support of his own contention, and to this day there is no little confusion in the public mind as to when and by whom the poem was written.

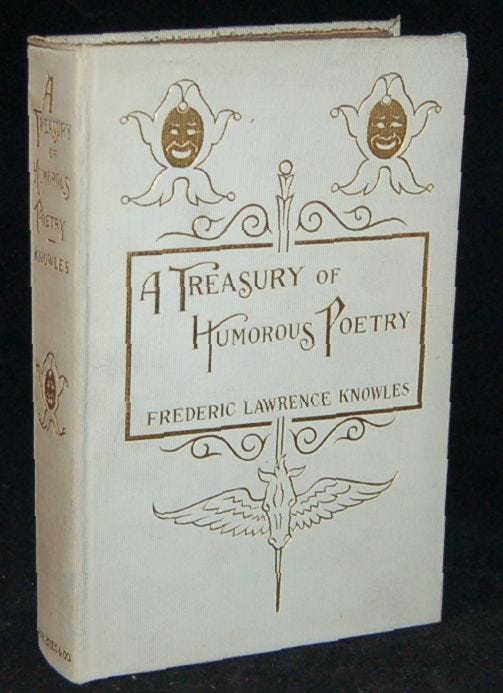

The first person to whom it was ascribed with some appearance of authority was Joseph Quinlan Murphy. In 1902 Frederic Lawrence Knowles edited an anthology called A Treasury of Humorous Poetry, and included an early version of “Casey at the Bat,” crediting it to Mr. Murphy. The only information about him was given in the index of authors, where it was

stated that he died in 1902. By the time anybody thought to question this, Mr. Knowles himself was dead, and his publishers could say nothing more than that he had always been very careful to trace the authorship of anything of which he was in doubt.

[Francis C.] Richter’s History and Records of Baseball states, in a chapter on “Writers on Baseball,” that Joseph Murphy was at one time on the staff of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, but the editor of that paper writes that “the oldest members of our editorial staff do not recall any person named Joseph Quinlan Murphy ever being connected with this paper. Joseph A. Murphy, nationally known racehorse judge, was sporting editor of the Globe-Democrat in the early ’eighties, but he has never been credited with the authorship of the poem, ‘Casey at the Bat.’ ” So who Joseph Quinlan Murphy was, as well as Mr. Knowles’s reasons for attributing the poem to him, remain a matter of conjecture. The publishers of A Treasury of Humorous Poetry, after some investigating of their own, evidently concluded that Mr. Knowles had made a mistake, for in recent editions of the book the poem is credited to Ernest L. Thayer.

Another man to whom the poem has been attributed was an Irishman named William Valentine, who died in the late ’nineties while on the staff of the New York World. The basis for his claim rests largely upon the evidence of Mr. Frank J. Wilstach, the compiler of the Dictionary of Similes. Here is the story as Mr. Wilstach has told it in two recent letters:

Will Valentine, a young Irishman, came up from the Kansas City Star to the Sioux City (Iowa) Tribune in 1885 to be city editor. He was constantly writing verse. On the back page of the Tribune I was at that time conducting a column which, shamefacedly I may say, was supposed to be like Eugene Field’s “Sharps and Flats” in the Chicago Record. It was bad; but Valentine every once in a while would hand me a bit of verse which I would run, he signing it “February 14,” being St. Valentine’s day, as ’twere.

Valentine and I were roommates. My brother Walter sent me a set of Macaulay’s works and one Sunday evening, reading “Horatius at the Bridge,” I said to Valentine that here was a good opportunity to parody “Horatius” by a poem about a Mick at the Bat. We were then baseball crazy. Valentine read the Macaulay poem and went ahead and wrote a piece he called “Casey at the Bat.”

It is rather curious that all the claimants for this poem have been seemingly unaware that “Casey at the Bat” is a parody on “Horatius at the Bridge,” with the same meter and the end of each stanza very nearly the same. I left Sioux City in 1887 and never heard of Valentine or thought anything of his poem until one night I met him on lower Broadway in 1898. I was then press agent at the Broadway Theatre and Valentine was employed on the New York World.

He promised to come to see me at the Broadway Theatre. About the first thing he mentioned to me at this meeting was that De Wolf Hopper, who was reciting his poem “Casey at the Bat,” was giving credit for its authorship to a man named Thayer. He asked me if I didn’t recall the fact that I had suggested “Casey at the Bat” to him in consequence of reading “Horatius at the Bridge.” I told him that I did recall it, but that I had forgotten all about it during the years intervening. I subsequently learned that Will Valentine died of typhoid fever while an employee of the New York World a few months after I met him.

This is a clear-cut narrative, but it is modified a little in Mr. Wilstach’s second letter, in which he says:

This matter of “Casey at the Bat” is so nebulous that I would really like to withdraw from it. However, I am certain of two things: first, that I suggested to Will Valentine that he write a burlesque of Macaulay’s “Horatius at the Bridge”; second that he did write this burlesque and that it was called “Casey at the Bat.” I was present in the room when he wrote it. I haven’t seen his copy since that afternoon, or a day or two afterwards, when it appeared in the Tribune. Whether the present “Casey at the Bat” is a re-write of Valentine’s I can’t say.

An inquiry of the Sioux City Tribune had previously elicited the information that Mr. Valentine had indeed been employed on the paper in 1887, but that there was no apparent foundation for the statement that he had written “Casey at the Bat.” It was also stated (by Mr. Thayer) that Mr. Valentine’s claim had been investigated about 1905 by the San Francisco law firm of Lent & Humphrey, who had sent an agent to Sioux City especially for that purpose, and that no evidence had been found to support it. But in view of the letters from Mr. Wilstach, it was evident that the only way to settle the question definitely was by a careful search of the Tribune files. Mr. John H. Kelly, the editor of the Tribune, was accordingly requested to have such a search made. He did so, and the following letter from him is self-explanatory:

We have had one of our men go over every copy of the Tribune during 1885–1888 inclusive, and he found the column referred to in your letter in numerous forms; but did not find the much sought “Casey at the Bat.” It would have been a very real pleasure and distinction to have claimed the great “Casey.”

So, whatever the poem was that Mr. Valentine wrote at Mr. Wilstach’s suggestion, it was evidently not the present “Casey at the Bat.” Indeed, this might fairly be inferred from Mr. Wilstach’s own letters, in which he emphasizes the fact that Mr. Valentine’s poem was written as a parody on “‘Horatius at the Bridge.” “Casey at the Bat” in no way suggests “Horatius” — except perhaps by a very faint similarity in the basic idea. But its form and character are entirely different, as the first stanza of “Horatius” will show:

Lars Porsena of Clusium

By the Nine Gods he swore

That the great house of Tarquin

Should suffer wrong no more.

By the Nine Gods he swore it,

And named a trysting-day,

And bade his messengers ride forth,

East and west and south and north,

To summon his array.

Part Two follows.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.