Ballad of the Republic: The Arming of the Man

August 14 is the date to celebrate the birthday of Ernest Lawrence Thayer (1863) and also the debut performance in 1888 of Thayer's "Casey at the Bat" by De Wolf Hopper at Wallack's Theatre at 30th and Broadway in New York City.

The poem "Casey at the Bat" captures the American spirit, the drama of Whitman's "hurrah game of the Republic," and the rough-hewn spectacle of the years when crowds cheered from wooden bleachers framing dusty diamonds. But the "Ballad of the Republic," as enigmatically subtitled by Thayer, has accrued a saga of its own behind which the true story of its origins has been long concealed.

Set in Cambridge and Worcester, Massachusetts, New York City, and San Francisco, shadowed by memories of the all-too-recent Civil War, the true story of "Casey's" origins reveals a rich diversity of characters such as erudite George Santayana; "born leader" and captain of the Harvard Nine, Samuel Ellsworth Winslow; ambitious William Randolph Hearst; and acerbic Civil War survivor, Examiner columnist Ambrose Bierce.

There is much about Thayer's biography, and the story of his "Casey" ballad, that has remained untold. Behind the origin of Thayer's ballad lies a tragic romance with the daughter of one of California's wealthiest forty-niners, involving a predatory West Point officer (see "The Love Song of E. 'Phineas' Thayer" elsewhere in this blog). Broadway's flamboyant De Wolf Hopper and self-made theatrical impresario John A. McCaull brought "Casey" to Broadway in 1888; but even as Hopper promoted "Casey" to the status of American folk hero, a ghostly literary impostor and his theatrical promoter tried to wrest the authorship of the "embattled ballad" from Thayer (see "In Search of the Counterfeit 'Casey'"). Even before the 20th anniversary of "Casey's" publication, a War Department investigation into the misdeeds of Thayer's one-time rival threatened to explode into headlines during the climax of the 1904 presidential election.

On the night of August 14, 1888--the evening of Ernest Thayer's 25th birthday--the curtain rises on the opening scene of Ballad of the Republic: Love, War, and Tragedy in the Saga of "Casey at the Bat:"

Chapter One: The Arming of the Man

"Our culture...must not omit the arming of the man. Let him hear in season that he is born into the state of war, and that the commonwealth and his own well-being require that he should not go dancing in the weeds of peace...."

--Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), "On Heroism" (1841)

"There is no chance in Cambridge for the young man of heroic intentions."

-- Ernest L. Thayer, (1863-1940) Harvard Class Day, Ivy Oration (1885)

Photograph of William T. Sherman in 1888. From this photograph was created the U.S. postage stamp issued in 1893

Wallack's Theatre, New York City: Evening of August 14, 1888

Concealed in the backstage shadows of Wallack's Theatre on the corner of Broadway and Thirtieth Street, "Colonel" John McCaull, theatrical entrepreneur and producer, stands watchfully, hands clasped behind his back. Outside under the blaze of electric light men flick cigarettes and half-smoked cigars into the gutter; inside, they rush up marble staircases to find their seats after intermission. In the curtained half-light McCaull savors--as he always does-- the momentary interval between expectation and revelation when the show will resume. Behind him he hears the quick firm step of German-born Mathilde Cottrelly, the former character actress to whom McCaull has entrusted all details of scenery, costumes, and stagecraft. They share a quick glance but exchange no words: both know that every note, line, and step has been rehearsed.

Interior of Wallack's Theatre, 30th and Broadway, 1880's

The theater life suits the Scottish-born McCaull in many ways. Particularly attractive to him is the way actors adopt the personalities and appearances of the characters they play--then shed them like snake-skins when the curtain falls. Like many young immigrants to America, McCaull swiftly grasped the possibilities afforded newcomers to adopt roles and opportunities which the Old World would never have offered.

"Colonel" John A. McCaull, from New York Press obituary, November 25, 1894

The McCaull family had found their way to Harper's Ferry, Virginia soon after their arrival in America in the mid-1850's. McCaull's father, also John, sought opportunity in the bustling industrial crossroads at the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers. As a shoemaker, the senior McCaull soon found employment in one of the local shoe and boot factories, but he had to work exceptionally hard to support six children on his own--his wife had died not long after the birth of Patrick in 1852. Agnes, the eldest, assumed housekeeping duties with the help of her sister Margaret. But the four boys created substantial aggravation within the household, especially the oldest, John. No doubt John Jr. was as "robustious" at age 15 as he would later be characterized by his peers in the theater business. By 1860 his father was doing well enough to send the boy to nearby Mount Saint Mary's College in Emmitsburg, Maryland--in the hope that John would pursue studies for the priesthood.

Bradley Hall, Mount St. Mary's University, by Greenhonda - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14734572

But the country's future, and John McCaull's, were about to change forever. The McCaull family had already glimpsed the trials ahead when abolitionist John Brown led a raid on the Harper's Ferry Armory and Arsenal, hoping to provoke a slave uprising. U.S. Marines under the command of colonel Robert E. Lee responded quickly to quell the violence, but from the day of Brown's capture on October 18, 1859, there would be no ebb in the tide of war. And for Harper's Ferry, the coming conflict would bring disaster and destruction: the town would change hands eight times between 1861 and 1865.

Harper's Ferry Armory, 1862, showing fire damage

For the robustious 15-year old John McCaull, there was no question of remaining in seminary while his hometown was threatened. In April of 1861, Union soldiers guarding the Armory set fire to the rifle works to prevent its falling into the hands of local militia, but town residents--probably including the McCaull boys-- helped rescue the weapon-manufacturing machinery to transport southward for Confederate use. In May, John very likely mingled with the freshly-minted militia milling about the streets of Harper's Ferry, assembled into companies of the First Maryland Infantry by Major Bradley T. Johnson, a graduate of Harvard Law School. By June, the departing Confederates would complete the destruction of the arsenal--but not before removing 17,000 gunstocks for shipment to North Carolina.

The volunteers of the First Maryland (CSA) and its successor regiment the Second Maryland would continue into the bloody battles of the eastern theater of the War as a unit of Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. No doubt young John McCaull had plenty of stories to tell about his real experiences, including his own family's dramatic view from the eye of the storm, as Harper's Ferry had become during the prelude to the war. McCaull would embroider the details of his soldiering and bolster his post-war recollections. But what is likely true, among the various versions of McCaull's retelling of it, is that he ended the War with ten cents in his pocket and the determination to become a lawyer and make a success of himself.

With the collapse of manufacturing and trade in Harper's Ferry--and the inclusion of the town in the newly-minted Union State of West Virginia--the McCaull family migrated westward into rural Pulaski County. In nearby Roanoke County, John, Jr. took an interest in horse breeding and politics, winning a seat in the post-war Virginia legislature and with his brother Patrick promoting the gubernatorial campaign and later U.S. Senate career of former Confederate General William Mahone. In 1879 John, Jr. left Virginia for Baltimore, where his former wartime commander Bradley T. Johnson was a practicing lawyer. The two became partners.

Ford's Theater, Washington D.C.

As a Baltimore attorney, McCaull backed into the musical theater business after he attempted a deal on behalf of client John T. Ford (of Ford's Theater in Washington, D.C.). Ford asked McCaull to help release him from a contract with D'Oyly Carte to produce the American debut of Gilbert & Sullivan's comic opera, "Pirates of Penzance." Failing to extricate Ford from his obligation, McCaull invested to become the "Pirates" co-producer--and found he could actually make money at this business.[1] Often chaffed about his former role in the Confederate forces, McCaull had a ready answer: "Who made this country, anyway? Where would the greatness have been if we hadn't rebelled? Who gave you fellows up North a chance to get rich and rob each other? Who enabled Grant to leave the tanner's store? Wouldn't Sherman still be out on the frontier mixing with the Indians instead of us? Why gentlemen, we have made you. You can't crow over us."[2]

McCaull appropriated a military title from his years with the Confederate army. Perhaps his regular exposure to comic opera characters, the dukes and princes peopling the imaginary kingdoms of musical drama, tempted McCaull to claim a more exalted rank than that which he had actually attained. As a mere stripling of 19 when Lee surrendered at Appomattox, McCaull had certainly not been a colonel commanding a Confederate battalion or regiment. Nor did the precocious teenager's actual service in the plodding infantry seem as glamorous after the war as his imagined career in the dashing cavalry. McCaull convinced more than one of his performers and associates, including De Wolf Hopper, that he had ridden with Alabama General John H. Morgan on the famous 1863 raid into Indiana and Ohio (he had not). Others believed he had joined a South Carolina artillery regiment which had fired the first shots at Fort Sumter.

John McCaull most likely served in the Virginia brigade of General William Mahone (above) during the Civil War. The McCaull brothers supported Mahone's post-war bid for the governorship and his successful 1881 campaign for the U.S. Senate.

So McCaull merely smiles to himself when former adversary Major General William Tecumseh Sherman returns to his reserved seat in the tenth row. Sherman has specifically requested the orchestra to refrain from playing "Marching Through Georgia"--the song that announced him wherever he went. Though on his arrival that evening men applauded his appearance, the old soldier, with a brief acknowledgment, occupied his seat and the excitement soon abated. Sherman, now residing in New York, has become a familiar face among theater audiences.

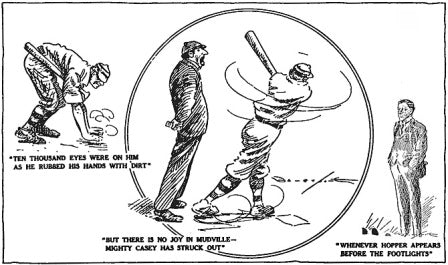

The performance this evening is the comic opera Prince Methusalem by Johann Strauss, and the star is the impressive De Wolf Hopper, a stand-out not only for his size (6'5", 230 lbs) but for the basso depth and tenor range of comic effects that his supple voice can project. Taking advantage of baseball fever sweeping New York to promote "baseball night" at Wallack's, McCaull has hosted for the performance both the visiting Chicago White Stockings and the home town Giants--both teams currently contending for the pennant. Knowing Hopper as a baseball "crank," as fans were called in those days, McCaull had the previous day handed Hopper a baseball poem clipped from the San Francisco Daily Examiner by McCaull's colleague, author and playwright Arch Gunter. In a couple of hours, Hopper memorized the thirteen-stanza ballad and layered on the dramatic effects and vocal emphases he intends to use. [5]

William De Wolf Hopper 1858-1935

Hopper, playing the Duke of the mythical kingdom of Trocadero, has just finished his bravura performance of "The Dotlet on the I," a comic turn within which various "base-ball" references had been cleverly inserted. Still glowing from the audience's accolades--including the presentation of an enormous baseball-shaped garland of maroon and white flowers -- the Giants' colors--Hopper steps out of character and asks the "kind permission of the audience" to recite a few verses for the evening's guests. Shouts of "Yes! Let's hear it!" bring a smile to his face.

"Everyone was on the qui vive," reported the New York Evening World in the following day's review. Had word somehow circulated of the special performance Hopper had been rehearsing? wonders McCaull. As the hush of anticipation falls over the crowd, General Sherman leans forward in his chair, so close to the graceful neck of the young lady seated in front of him that the Evening World reporter wonders if he intends to kiss her. [6]

McCaull watches intently as the tall, elaborately costumed Hopper steps into the limelight-- quite literally, into a pool of light produced by a block of superheated limestone, focused by reflectors into a beam directed from the balcony onto the stage. Meanwhile, giant fans in the theater's basement propel air across tons of ice and up stairways to keep the audience tolerably comfortable despite the day's heat lingering in the streets outdoors.

Standing in an elocutionary pose before the footlights, Hopper begins, in a mesmerizing, exquisitely modulated tone:

The outlook wasn't brilliant for the Mudville nine that day;

The score stood four to two with but one inning left to play.....

The audience is drawn instantly into the tale, recognizing at once the inherent drama of the hometown team teetering on the precipice of defeat, yet given a last desperate chance at victory by their renowned batsman. The language of Hopper's performance, too, is strangely moving--not with the clever rhymes and comic wordplay of the ditties they had already heard that evening in Strauss's operetta--but in phrases elevating the duel between striker and hurler to the sublime heights of an epic struggle...

House at Chatham and Crown Streets, in the Crown Hill neighborhood in Worcester, adjacent to the former Thayer residence at 67 Chatham Street (long since demolished). This historic home hints at the size and elegance of the Thayers' residence, which stood just across Crown Street in 1888 (author's photograph)

67 Chatham Street, Worcester, Massachusetts: Evening of August 14, 1888

Two hundred miles north of Broadway, across the dark wooded hills and rushing rivers of southern New England, a young man sat at an upstairs window in his father's Crown Hill home overlooking the bustling heart of Worcester. This day was Ernest Thayer's twenty-fifth birthday, and for the occasion his sister Nellie had bought him the Charles Cotton translation of Montaigne's essays. Nellie and her husband Sam did not linger after dinner and dessert, excusing themselves with bedtime for Ernest's namesake nephew, now eighteen months old. Brother Edward and his wife Florence remained, politely but briefly, for port and small talk with Ernest and Edward, Sr. But tomorrow was a work day, and Edward, Jr. would be up and about by six o'clock. Shortly after seven, Edward would collect Ernest for their four-mile ride to Cherry Valley, where Ed managed the family woolen mill and Ernest kept the books, tracked the inventory, and studied the numbers.

Unready for sleep, Ernest idly turned the pages of his gift in the lingering light. As night fell, the clamor of the cicadas rose to a crescendo. Katydids took up their own rhythmic chant; above their register the crickets piped a descant. But to the young man at the bedroom window the evening chorus was audible only as a faint creaking and clattering. Impaired hearing, the residue of a childhood illness, had marked Ernest with a guarded shyness. Those who knew Thayer by mere acquaintance wrongly regarded him as supercilious and detached. To the contrary, Ernest's demeanor masked a keen sensitivity to the absurdities of life. And where his hearing faltered, a vivid imagination filled in the gaps. Annoying though it was, Ernest's impairment (in an absurd paradox he himself recognized) was the source of his unconventional, self-deprecating humor.

A cool breeze stirred the curtains. Across the stable yard, under the elegant cornices of neighboring homes on Crown Hill Street, lamps shone through upstairs windows as the early-risers prepared to retire for the evening. In the fading light Ernest's eyes were drawn irresistibly to the essay on marriage: "Marriage is like a cage," Montaigne had written. "One sees the birds outside desperate to get in, and those inside desperate to get out."

"Well, damn it!" Ernest swore. Unbidden memories of his birthday a year ago in San Francisco came rushing back: Thayer propped weepily on the bar at Wagner's, with the reliable Fatty Briggs at his elbow and a "pretty waiter girl" offering her gentle consolations. Thayer could smell the cigar smoke, the damp sawdust underfoot, the ghost of the girl's perfume. And what was that Strauss tune she claimed was her favorite--"Roses from the South?" The reedy chords of the melodeon echoed through labyrinths of a faded dream. Ernest decided he had read enough of Montaigne for one evening. He tossed the book aside, spilling the glass of sumac lemonade left half-empty on the desk. "Damn it," he muttered to himself, and stood to blot the spill with his handkerchief. What would Montaigne know about it, anyway?

Wallack's Theater, August 14, 1888

As Hopper reaches the dramatic climax of his narrative, the audience strains to hear every word:

And now the pitcher holds the ball, and now he lets it go,

And now the air is shattered by the force of Casey's blow....

The final stanza evokes a springtime vision of a small-town landscape in post-Civil-War America, a scene that would remain unchanged in many ways from 1888 through the next seventy years and more: where brass bands perform on the municipal common, where children play their games on the darkening green, reluctantly dropping bat and ball in response to the distant parental summons; where a genteel civic satisfaction suffuses the evening with the expectation of rest and a brilliant day to follow on the morning's horizon. But with Hopper's doom-laden pronouncement: "Mighty Casey has struck out," that vision is shattered.

There is a moment of shocked silence. Then the audience roars without restraint: they have heard nothing like this before. According to the Chicago InterOcean "...'Casey at the Bat' convulsed the audience with laughter."[3] And moreover, wrote the reporter from the New York World, "Men got up on their seats and cheered, while old Gen. Sherman laughed until the tears ran down his cheeks. It was one of the wildest scenes ever seen in a theater and showed the popularity of Hopper and of baseball."[4]

For sixty-eight-year-old General Sherman, sitting alone in the semi-darkness, Hopper's rendition strikes a familiar note. "Where," he wonders, "have I heard this poem before--or something like it?" The dramatic stanzas of "Casey"--tonight performed for the first time--echo the cadences of martial ballads beloved by Sherman's generation. In the modulated rhythm of Hopper's recitation Sherman hears the tread of boys advancing to his orders across blazing fields and up rocky mountainsides.

But as Sherman sits laughing, and crying, the old soldier realizes the emotions that have so stirred him have claimed their inevitable price--an attack of the asthma that has troubled him all his life. Sherman puts his head back, looks up at the stage lights, and wheezes. His eyes dim. As he gasps for air, the amused, sardonic voice he has often heard in the midst of battle speaks to him again: "You could laugh yourself to death, old man."

Kennesaw Mountain, Georgia: June 27, 1864

High in a hickory tree Major General Sherman squinted through a telescope mounted to the rail of his command post. Across a wide valley on the opposing ridge his focus narrowed to a salient of the fortifications of Joe Johnston's Army of Tennessee. This promontory along the rocky crest of a hill would later become known as Cheatham's Hill, after Major General Benjamin Cheatham commanding this sector of the Confederate defenses. Against this point Sherman had arrayed his best divisions and assigned their objective--to knock out Johnston's army at one bold stroke, opening the gateway to Georgia's heartland. The Kennesaw Mountain entrenchments, cunningly engineered to repel any assault, represented the most formidable barrier between Sherman's army and Atlanta--the Confederacy's vital railroad junction and manufacturing center.

Sherman had assigned the leading role to the Second Division of the Fourteenth Corps, Army of the Cumberland---the Second Division, commanded by the incongruously named Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis. Among the units committed to the attack would be Davis's Third Brigade led by Sherman's fellow Ohioan Colonel Daniel McCook, Jr., with whom Sherman and his brothers-in-law Tom and Hugh Ewing had opened a law office in Leavenworth, Kansas in 1858.

Even in Sherman's shaded aerie the heat was already oppressive, and it was not yet nine o'clock. Sherman chewed anxiously on his cigar, scanning the opposing crest. The general knew that if anyone could storm the entrenchments and put Johnston's army to flight, it would be Dan McCook. "Like Missionary Ridge," he thought to himself. The previous November, Union General George Thomas's Army of the Cumberland—Colonel McCook and his Ohio regiment among them--had swarmed up the forbidding promontories overlooking the Tennessee River. Against formidable odds they had routed General Braxton Bragg's army, breaking the siege of Chattanooga.

"Colonel Dan," as his soldiers called him, was one of seventeen McCook sons, uncles, brothers, and cousins from Ohio who would fight for the Union. McCook had so strenuously trained his first command--the 52nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry regiment--that his men heartily disliked him. Only after the battle of Perryville, Kentucky in October 1862 had they cheered his leadership and granted him the affection that matched their respect. Impetuous, ambitious for advancement, always ready to argue for his chance to lead and fight, Dan had distinguished himself in battle in 1862 and 1863. But his aggressiveness off the field and willingness to challenge perceived slights had not endeared him to his superior officers--including Ulysses S. Grant. When McCook's former law partner "Cump" Sherman took over the command of Federal armies facing Joe Johnston in Tennessee, McCook was hopeful for a chance to demonstrate the fighting abilities of his brigade.

By his own reckoning, the fierce warrior Dan McCook, Jr. was one of the most cosmopolitan of Sherman's officers. Troubled by respiratory problems during his youth in the Ohio Valley, he had been sent to the supposedly drier climate of Leighton, Alabama, to LaGrange College. Here his health improved: he played sports, took part in the Literary and Debating Society, and wrote for the college newspaper. He graduated in 1857 and returned to his brother's home in Steubenville, Ohio to study law. But on the morning of June 27, 1864 it was only a matter of chance--in this war involving so many bitter coincidences--that McCook would not confront former schoolmates, faculty, and other friends who had enlisted in the 35th Alabama Infantry from LaGrange College and the surrounding counties.

Further complicating Dan's loyalties at the outbreak of the war had been his marriage in 1860 to Julia Tebbs, a belle from Leesburg, Virginia. In a pre-war letter to his brother George, Dan revealed both his grounding in ancient history and his doubtfulness about the justification for war:

As the "war clouds lower," my old army fever returns; but like the Huns as they hovered upon the Danube, menacing both Constantinople and Rome, I am hesitating against which Empire to turn my "weighty sword." The "tangled woof of wrong" enwarps both causes.

The rebel attack on Fort Sumter put an end to ambiguity: Dan and his partners Sherman and Ewing offered their services to the Federal government. After the battle of Shiloh, where Dan's brother Alex and his division had marched to Sherman's (and Grant's) rescue, Dan left his brother's staff and returned to Ohio, where he began to recruit the 52nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry regiment. He would command the 52nd in various roles for the rest of his Army career. Riding horseback throughout eastern Ohio, McCook exercised his talent for persuasion, exhorting scores of volunteers to fill ten companies of the regiment. It was likely during his tour of the Ohio river towns and crossroad villages of Belmont and Jefferson counties that McCook began to employ inspirational lines memorized from Thomas Babington Macaulay's poem, "Horatius."

These verses returned to McCook as he paced among his regiments, while the Union batteries rained metal upon the heights. "The heavens seemed made of brass," recalled one of the Tennesseans dug in on Cheatham's hill. As sharpshooter rifles began to crackle from the rebel works, Dan ordered his men to the ground. A corporal objected that McCook was equally at risk, and the Colonel replied: "'Tis an easy matter to fill my place and a very hard matter to fill yours. Now lie down."

At nine o'clock, the Union cannonade ceased, leaving only the sweet trampled fragrance of an unmown Georgia hillside. A red-winged blackbird whirred from the creek line below, and behind it rose the metallic clatter of cicadas. McCook stepped to the center of the brigade, the regiments now formed into columns, one behind the other, the 125th Illinois leading. Soldiers of the 85th Illinois fanned out in advance as skirmishers to drive in the Confederate outposts.

KK

Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park today

The 52nd Ohio brought up the rear of the brigade column, its regimental colors of dark blue silk stirring almost imperceptibly in a wisp of breeze. Hundreds of men of McCook's first command, recruited from the cities of St. Clairsville and Martin's Ferry, and from crossroad hamlets of Bethesda, Powhatan Point, and Armstrong's Mills, dressed their ranks and repressed their fears. Sweat trickled down their backs under their dark woolen coats. Peering upward at the wooded ridge ascending from the valley before them, one lanky veteran of the 52nd's previous engagements remarked to no one in particular, "Reckon we'll ketch hell over'n 'em trees."

No one from his company responded. As twilight extinguished yesterday's fiery sunset, the sight of officers riding along the front awakened presentiments among the Ohioans of what dawn would bring. Letters to families and sweethearts were entrusted to comrades behind the lines or tucked into heavy packs, now carefully stacked and guarded. In battle, men carried only their Springfield rifles, cartridge boxes on their belts with forty rounds each--inspected carefully by the sergeants--and their light haversacks. Now they could hear McCook's strong, tenor voice, in a kind of chant it seemed to them, reminding them of the day he had summoned them from their farms and villages to preserve the Union:

Then out spoke brave Horatius

The captain of the gate;

"To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds

For the ashes of his fathers

And the temples of his gods?"

Then came the dread summons all would obey. On the column's left, there was a salvo from a six-gun battery--the signal for the advance. Drawing his sword, McCook pointed upward to the center of the Confederate stronghold. "Forward!" he shouted. From his watch-post above and behind the Union line, peering through his telescope, General Sherman saw the blue ranks sway as the brigade stepped out.

McCook's exhortation from "Horatius" was remembered in detail by many of those present. Harking back to that day more than thirty years later, Lieutenant J. T. Holmes wrote "I recalled McCook's death song as he strode through the brigade and the actual work before us, of which we had been advised, began to dawn clearly on all minds." (Then and Now: 52nd O.V.I., Volume 1 {Columbus, Ohio: The Berlin Printing Company, 1898}, p. 177). "It was doubtless, a spontaneous quotation," wrote Holmes, "but very appropriate to inspire the patriotic feeling and, if we had been Roman soldiery, a trust in the care of the gods. It was a heathen refrain, but impregnated with love of country and kith and kin and duty owed to them all."

Details of the battle are further elaborated and supported by Earl J. Hess, Kennesaw Mountain: Sherman, Johnston, and the Atlanta Campaign (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013 pp. 118 ff; and Russell W. Blount, Jr., Clash at Kennesaw June & July 1864 (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Co.), 2012, pp. 95-119. Contemporary accounts by officers in the 52nd Ohio, J. T. Holmes and F. B. James provide the key original sources.

Notes

[1] See Stephen E. Busch, "John A. McCaull Comic Opera Companies" (http://www.operaoldcolo.info; also New York Sun, 14 Nov 1894 , p. 5). In another version of McCaull's involvement with John Ford and his theater, McCaull was brought in to resolve a dispute with the theater's orchestra. Actually both versions may be true; neither is necessarily exclusive of the other. See Michael Green, "The Odd Couple Who Paved the Way for Modern Broadway," NewYorkAlmanack.com, November 16, 2020.

[2] "Colonel McCaull's Retort," reprinted from the Chicago Herald in the Daily Examiner (San Francisco), Sept. 25, 1887.

[3] Chicago InterOcean, 15 August 1888.

[4] New York World, 15 August 1888, quoted in John Evangelist Walsh, The Night Casey Was Born: The True Story Behind the Great American Ballad "Casey at the Bat" (New York: The Overland Press, 2012), p. 132. Walsh's account of the background to "Casey's" debut performance is a must-read for baseball enthusiasts.

[5] A more poignant variant of this story is also told: In this version, Hopper was supposed to have received the poem only on the day of the performance, and intended to memorize the poem between acts. But before curtain time that evening, Hopper received a telegram from his wife that his two-year-old son, John Allan, was seriously ill. Too distraught to proceed with his plan, Hopper intended to set the poem aside; but a second telegram quickly arrived with the news that his son was recovering. Relieved and inspired, Hopper quickly memorized the anonymous ballad and delivered it that evening to instant acclaim. From that moment on, Hopper's fortune and that of "Casey" were inextricably linked. Ann T. Keene, in American National Biography Online (September 2005)

[6] This detail is found in "Hopper Was at the Bat," New York Evening World, 15 August 1888.

Cover Illustration by Captain Otto Boetticher of the 68th New York Volunteers, one of the POW's. Lithographic firm Sarony, Major, & Knapp, Published by Goupil & Co. 1863 date drawn: mid 1862, published date: 1863, courtesy National Museum of American History, catalog # 60.3741.

Drawn from life on July 4, 1862, the baseball game pictured in this print was played by Union soldiers at Salisbury Confederate Prison in North Carolina. Between December 9, 1861 and February 17, 1865, the prison housed 10,000-15,000 Union prisoners of war and other assorted detainees. Thomas W. Gilbert notes in How Baseball Happened: The True Story Revealed, "Many, if not all, of the figures are portraits of actual individuals, including the Irish American hero Colonel Michael Corcoran, who is seated furthest to the right." (p. 280)

#CaseyattheBlog #BalladoftheRepublic @thorn_john @BaseballHX @TheLambsInc @BBHistoryDaily @PaineProffitt #ErnestThayer @WooSox @BaseballHx

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.