Casey on the Bench 1897-1900: Mighty Hopper Strikes Out

Thanks to Anika Orrock, artist, author, and illustrator of the featured image above ("The Mudville Nine"), used here with her permission. Of all the many artworks bringing to life Ernest Thayer's 1888 ballad "Casey at the Bat," only Orrock has ever rendered the Mudville Nine side-by-side on the dugout bench! (Can you guess which player is Casey?) Commissioned originally by the National Pastime Museum as part of a series by known baseball artists, the Casey at the Bat Project was envisioned as part of a "virtual reliquary" intended to educate the public about the history and significance of baseball in American culture. And Orrock's charming interpretation of the Mudville Nine, for whom "the outlook wasn't brilliant," creates the perfect introduction to an episode in the saga of the "Ballad of the Republic" (as the poem was subtitled by Thayer) when the legendary slugger was banished to the dugout by none other than "Casey's" foremost interpreter and promoter, Broadway star DeWolf Hopper (1858-1935). [1]

One of the lesser-known but enduring "Casey" mysteries to be solved is why, with the poem's popularity growing with every recital, did DeWolf Hopper take an extended hiatus from performances of the Mudville drama? Since August 14, 1888 Hopper had been performing "Casey at the Bat" to wild acclaim throughout the country, presenting it as an entr'acte recitation during his comic opera appearances.

An 1897 version of an encounter between Hopper and Thayer suggests Hopper even attempted to blame Thayer himself for the disappearance of "Casey" from the actor's repertoire during the late 1890's!

In the Piqua Daily Call (Piqua, Ohio), July 8, 1897, Hopper described a meeting with Thayer--not at the Worcester Club in 1892, where the first encounter between the two has been documented, but rather at the Players' Club in New York. [2]

It is probable that Hopper and Thayer met on more than one occasion during the 1890's. Even if these separate accounts can be explained as variations of the same event, the Piqua Daily Call story provides additional insight into Hopper’s character if not into Thayer’s. In Hopper's retelling of the encounter, gone is the "big, manly-looking fellow" Hopper described to a Kansas City Star reporter in 1895. Rather, Hopper expresses his surprise at Thayer’s slight, pale, “effeminate” appearance, and his disappointment at the way Thayer recited his own poem. (We are familiar with Hopper's histrionic recital of “Casey” because we have gramophone recordings of his performance made years later). The question is whether Hopper's recollection is of the earlier meeting as reported by newspapers at the Worcester Club in 1892, or if he is recalling a subsequent meeting between himself and Thayer in New York.

"Casey at the Bat," Piqua Daily Call, July 8, 1897

In the 1892 version of the first meeting between the two men, Hopper had been invited by Thayer to the Worcester Club following a performance at the Worcester Theatre. But in Hopper's 1897 account, Thayer is Hopper's guest ("I think at the Players' Club, New York" recalled Hopper) accompanied by other actor friends. In several particulars, the following anecdote sounds like a different episode from that of their first meeting.

Players Club, New York (courtesy Untapped Cities blog, Michelle Young)

Hopper’s method of story-telling, with himself at the center, reveals a man of extravagant self-confidence common to many actors: a raconteur, a fabulist, a joker. This story carries the style of an anecdote related by Hopper to the reporter over a drink and a cigar. Imagine an after-theater celebration at the Player's Club (although based on variant versions Hopper may well have misremembered the place and time), with the young industrialist Thayer in his high collar and trim dark suit, appearing very out of place among this colorful, high-spirited group; the enormous thirty-four year old Hopper (six feet, five inches tall, well over two hundred pounds) at the peak of his profession, relaxing with fellow actors in a private dining room following a performance, with their coats off and ties loosened, decompressing with plenty of liquor. Knowing Thayer, we imagine his lifelong shyness and reluctance to recite his masterwork, Hopper’s “heartbroken” reaction to Thayer’s effort, and Hopper's immediate self-flattering thought that he, Hopper, had instinctively “ had the correct idea ” in interpreting the poem. Finally, Hopper's drunken actor friend, with manners outweighing his honesty perhaps, suggested diplomatically to Hopper, “I think you could make it go better that way.” And finally Hopper’s punch line to the news reporter, “Perhaps you understand why I don’t recite the thing any more.”

DeWolf Hopper radio performance of "Casey at the Bat," 1920's

This 1897 rendition of course did not mark the end of Hopper's relationship with "Casey." We know that the actor resumed recitation of the baseball ballad to audiences all over the country--and eventually to radio audiences-- for decades into the future. In June of that same year, 1897, newspapers reported that Hopper was giving his "Casey" performance to a crowd on Pike's Peak, then crowing via telegram afterwards that this feat had established his reputation as being "the highest and most wonderful actor in the world." In this light, it is not hard to imagine Hopper following Thayer's recitation in the old "let me show you how it's done" spirit with his own well-honed "Casey"--to the dinner party's delight and to Thayer's embarrassment.[3]

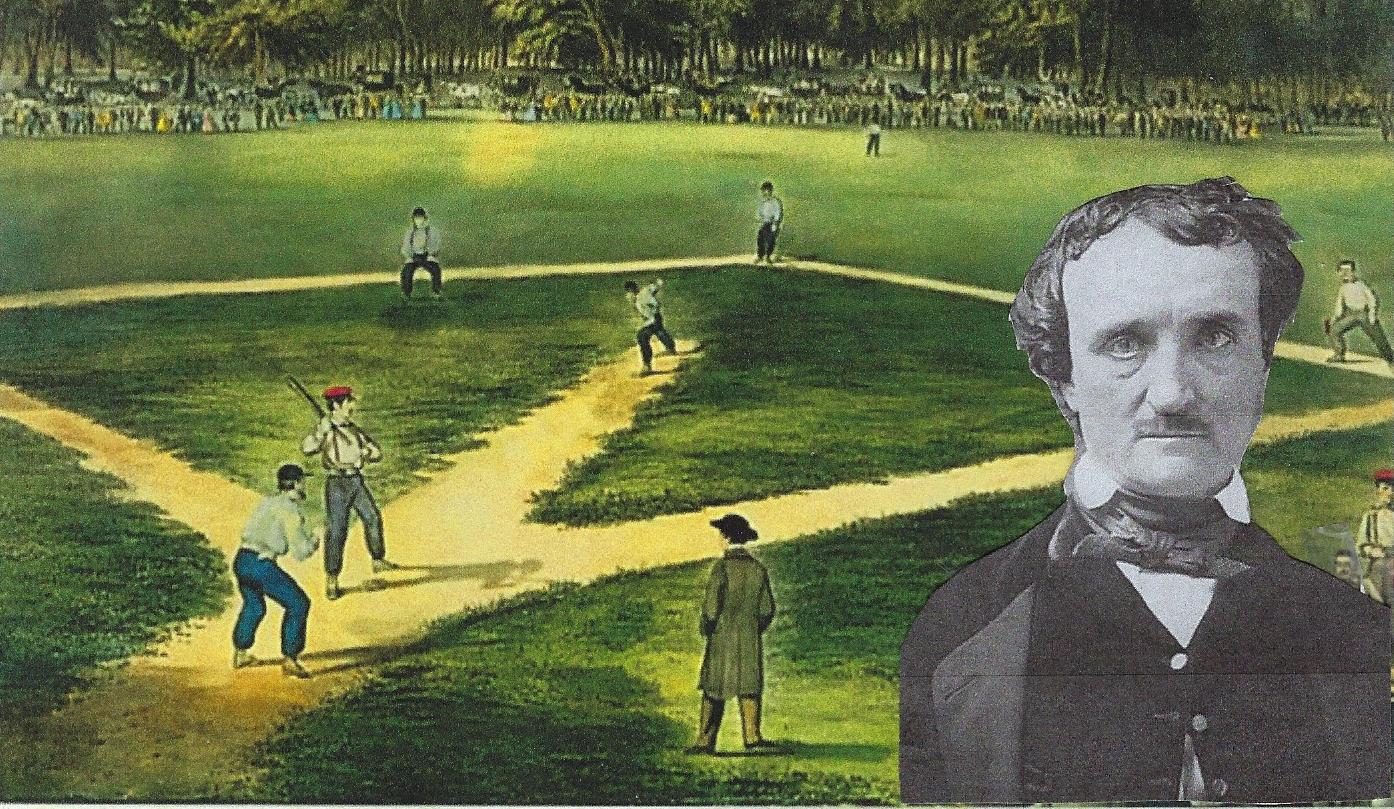

Images of DeWolf Hopper (ca 1901) and Ernest Thayer (ca 1903)

But such was the outsized character claimed by Thayer in 1908 as his friend. If indeed a friendship, it is certainly one which required a good deal of forbearance on Thayer's part. Or did Thayer, in his self-effacing way, come to ignore or tolerate Hopper's backhanded accolades at the shy balladeer's expense? Even in the newspaper era, such anecdotes (especially as told by celebrities like DeWolf Hopper) were copied and reprinted in other news articles around the country; Thayer would not have been ignorant of the kinds of things that Hopper was saying about him. Yet whatever his shortcomings as a friend, Hopper was the principal enthusiast and promoter of "Casey" and a lifelong defender of Thayer's sole authorship.

By 1895, Hopper was touring again, this time with his own company, He had first produced the comic opera "Wang," a take-off on the Gilbert & Sullivan Mikado, at the Broadway Theatre in New York in 1891. Hopper himself starred in the role of the Regent of Siam opposite the diminutive Della Fox, who appeared in tights--appropriately in a "trouser role" as the Crown Prince. "Wang" ran for one hundred and fifty-one performances in New York in 1891, went on tour in 1892, and was revived in 1904 at the Lyric Theatre. By the time Hopper met Thayer at the Worcester Theatre in December 1892, he had been performing "Casey" almost nightly and to growing acclaim.

Poster for DeWolf Hopper in Wang, which toured in the 1890's. Hopper appeared in a production of this musical comedy in 1892 in Worcester, where he met with Thayer for the first--and perhaps not the only--time

When the Hopper company went west in 1895, it was not with Della Fox but with another diminutive actress to offset Hopper's own formidable stage presence. This time the actress was his wife Edna Wallace, whom he had married in June of the same year. A review of "Wang" in the Salt Lake Tribune[4] in November noted (with a curious mix of mammalian metaphors) that while Hopper was the "diamond" in the setting of the production,

His wife, Edna Wallace, petite, graceful, and bewitching, is a regular minx. Beside her husband, she looks like a fawn by a high-antlered deer. Her voice is sweet and magnetic, though light.

Edna's assertive personality, however, was more than a match for Hopper's physicality. Though Hopper makes no mention of it in his autobiography, by 1897 he had begun to take an extended break from reciting the ever-popular "Casey" though audiences continued to clamor for it. Recall that in July 1897, Hopper had recounted his disillusionment with Thayer's recitation of "Casey," ending with the punch line, "Perhaps you understand why I don't recite the thing anymore."[5] Thereafter the Fort Wayne News (January 27, 1898), reprinting an article from the Chicago Tribune, reported

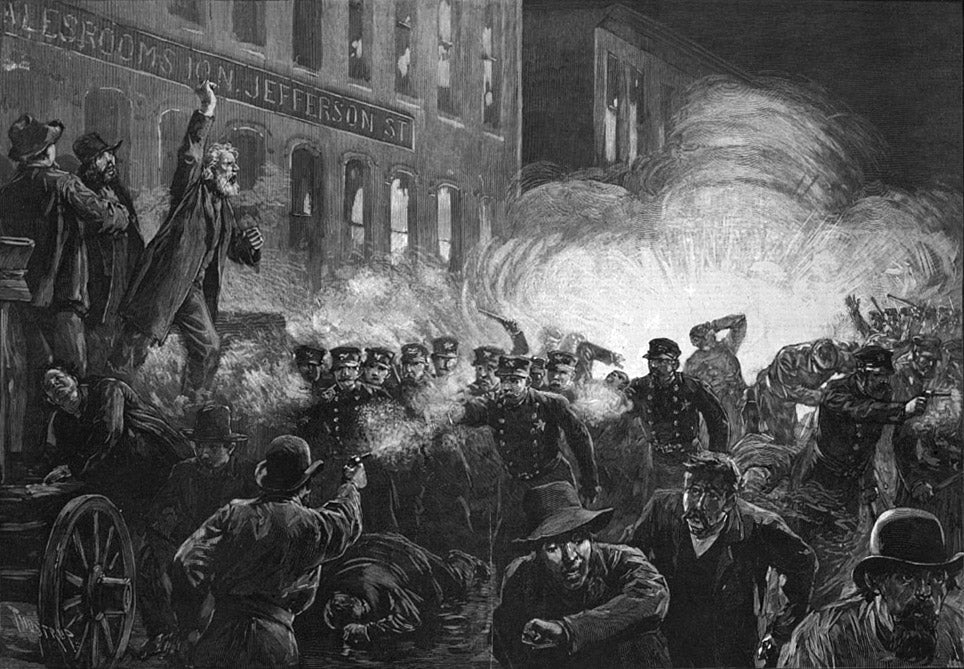

Mr. DeWolf Hopper awakened a gallery demonstration that threatened at one time almost to assume the form of a riot at the Columbia {a Chicago theater} last night. He refused to recite "Casey at the Bat." After the first act there were the usual recalls and the usual demands for a speech, and for the epic so intimately connected with Mr. Hopper's artistic career. The speech was granted, but "Casey" was not. The comedian promised some gems of thought after the next act, and his more ardent admirers grew solemn at the prospect. When the second act closed, with waving of flags, a brass band and other politico-military accessories, the curtain was rung up and Sousa's "Stars and Stripes Forever" was given as an encore. Unsatisfied with a second speech, failing to end with "Casey," the feelings of the gallery, preyed upon by mingled emotions, required a bit of police interference to calm them.

Here at the Columbia Theater in Chicago the audience nearly rioted in January 1898 when DeWolf Hopper refused to perform his popular recitation of "Casey at the Bat." On March 30, 1900, a fire in the Iroquois Club laundry (on the 6th floor) brought down the entire building, including the theater, which had been built by J. H. Haverly soon after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

It is tempting to speculate that, just as Arthur Conan Doyle had attempted in 1893 to slay his creation, Sherlock Holmes, Hopper may have resented from time to time the irrepressible popularity of the doomed slugger-- which in some ways both defined and eclipsed Hopper's personal renown as an artist. Newspaper accounts provide evidence that for some period from mid-1897 onward, Hopper had been trying to get out from under the growing popular demand for "Casey's" performance.

Sydney Paget's illustration of the supposed death of Sherlock Holmes at the Reichenbach Falls

But as to the 1897-1900 lapse in Hopper's performances of "Casey," there is a simpler and more compelling explanation than Hopper's anecdotes of his disillusionment with Thayer's own narration of "Casey." Found in the following show-business gossip column in the Chicago Inter-Ocean (May 30, 1897) is the following:

This is evidence that the twenty-five-year-old Edna, who appeared with Hopper in several comic operas including Souza's El Capitan , had pressured Hopper during this period to desist from his comic recitations. Typically the "Casey" performances were demanded by the audience during intermissions or interludes within the comic operas in which Hopper starred. It is easy to imagine Wallace's irritation at the lengthy interruptions between acts while Hopper worked the house for laughter and applause. But the episode of the near-riot in Chicago in 1898 when the audience was denied the satisfaction "Casey" suggests that the formidable Hopper preferred the wrath of the crowd to his wife's backstage fury.

Actress Edna Wallace Hopper (1872-1959), in a photograph dated 1910. She and DeWolf Hopper were married from 1895 until their divorce in 1898. Hopper mentions Edna fondly in his 1927 autobiography. Their stage appearances together accentuated the contrasts between the two: DeWolf was 6'5" while Edna stood barely 5 feet in height. Following a colorful stage career, Edna would go on to become the only woman on the board of Wall Street's L. F. Rothschild & Co. She died in 1959. Source: U.S. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Neither Hopper, the leading comic actor of the era, nor Lillian Russell, the country's leading female entertainer--"The American Beauty" as she was popularly titled--was ever a match for the petite but supremely confident Edna Wallace. Not only did Edna prevail in her showdown with Hopper over the "Casey" recitations, but in 1899 she was quite ready to upstage the acclaimed Lillian during their joint appearance in a performance of La Belle Helene at New York's Casino Theater. Edna's selection of increasingly scanty costumes for the production provoked not only audience acclaim but Lillian's wrath (Russell, a voluptuous beauty, became reluctant to wear tights in her maturity and successfully sued a producer who insisted on this feature of her costume). The contest between Russell and Wallace simmered through an East Coast tour of La Belle Helene until Edna, with a high-kicking dance routine in her risqué outfit garnered more applause during curtain calls than Lillian. Russell wired her producer, George Lederer, that she could no longer perform with Edna Wallace and then quit the show, which finished not only the tour but the entire production. Lederer sued Russell for $15,000 in damages and Lillian and her attorneys contested the suit[6].

Lillian Russell (1861-1922), ca 1890. Neither "The American Beauty" nor DeWolf Hopper could contend with the diminutive Edna Wallace, who outperformed and upstaged both

The Hopper-Wallace marriage lasted only until 1898. It is apparent from the Inter-Ocean's 1897 gossip column that whatever the status of the Wallace-Hopper union at that time, there was certainly no love lost between Edna Wallace and The Mighty Casey. The $100 fine imposed by Edna for a recitation of "Casey" may have been one of Hopper's fables, but if true, $100 was no mean sum in 1897, when average wages in industry, trade and transportation were around $665 a year. The self-assurance in the young actress's demeanor-- in the Library of Congress photo above--suggests Edna was not one to suffer fools gladly. Nor, as DeWolf discovered very soon, did Edna extend forbearance to clowns--especially to a self-proclaimed one like DeWolf Hopper (Once a Clown, Always a Clown was the subtitle of his 1927 autobiography). "Casey at the Bat" may not have severed the Wallace / Hopper union but Edna's intolerance of Hopper's performance of the poem provides a small insight into the perils of a match between two strong personalities whose discord could not escape the public eye.

So the mysterious gap in Hopper's performances of "Casey" can be explained by Edna's well-known antipathy to the poem--or at least to Hopper's recitations of it. Wallace and Hopper divorced in 1898, yet it would be another couple of years before Hopper resumed his dramatization of "Casey at the Bat" for audiences who continued to clamor for the ballad of the legendary slugger. In the meantime, notwithstanding Edna's aversion to the Mudville drama and Hopper's failure to challenge Edna's edict, The Mighty Casey by the turn of the 20th century--no longer confined to the bench--was ascending inexorably toward the pantheon of American Legends.

1996 U.S. Postage stamp set: "Folk Heroes"

1996 U.S. Postage stamp set: "Folk Heroes"

[1] Anika Orrock, cartoonist, illustrator, designer, writer, humorist, archivist and baseball aficionada is the author and illustrator of The Incredible Women of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2020). Her captivating and colorfully-illustrated story of the 1943-1954 women's professional baseball league popularized by the 1992 movie A League of Their Own is not only a lively historical account, with engaging first-hand vignettes provided by the players themselves, but also a necessary reminder that baseball is not a game to be played only by men. In fact, women's baseball organizations and competitions are established not only in North America but in other countries around the world! And today women like Jean Afterman (who wrote the Foreword to The Incredible Women), Julie Croteau, Kim Ng, Rachel Balkovec, Alyssa Nakken, and Bianca Smith are making their way into management and coaching positions in NCAA men's baseball and in MLB itself.

As Anika Orrock writes in her introduction, "...there is so much more to the real story of the All-American Girls Baseball League than can be gleaned from a two-hour film, and who better to tell it than the incredible women who lived it?" Caseyatthe.blog highly recommends this well-crafted book to baseball fans and especially to the girls and young women who want to coach, umpire, manage but especially to take the field and play America's national pastime!

Regarding her unique portrayal of Casey and The Mudville Nine commissioned by the National Pastime Museum, Orrock writes, "For better or worse, I've never been one to stick to the path. I'll listen carefully to instructions and follow the rules that really matter, but I've always been the kid who wanders away from the tour group to investigate the thing we're not there to learn about. I'm the weird kid who took the assignment of "Casey at the Bat" and put him on the bench."

[2] Minneapolis Times quoted by the Piqua Daily Call, July 8, 1897

[3] Thayer, known to be ill-at-ease in social situations, had some familiarity with the theatrical life from burlesques produced by the Hasty Pudding Club at Harvard. During his time in San Francisco, Phoebe Hearst--William Randolph's mother-- had also commissioned Ernest to write a play for a charity event performed at the Grand Opera in San Francisco.

[4] Salt Lake Tribune, 8 November 1895.

[5] Minneapolis Times / Piqua Daily Call, ibid.

[6] See for this account of the Russell -Wallace feud, Armond Fields, Lillian Russell: A Biography of "America's Beauty" (Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 1999), pp. 117-118.

#BalladoftheRepublic #DeWolfHopper #CaseyattheBat #TheLambsClub #ErnestThayer #AnikaOrrock #AAGPBL

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.