Ambrose Bierce and The Fall of the Republic

Demagogues fixed a predatory eye on the inherent flaws of the American Republic. Like buzzards they circled the wounded behemoth thrashing in a bog, while a mob assembled on the grounds of the United States Capitol--some carrying concealed weapons. Police braced for an assault while political adventurers jockeyed for the chance to ride the tiger of mob violence. As the opposing forces squared off for an apocalyptic showdown, a wild rumor swept the crowd...

Journalist Ambrose Bierce envisioned such a cataclysm in 1888. "Looking back" from a notional perspective of the 31st century to his own era, he stuck the stiletto of his satire into the premises of Edward Bellamy's utopian novel Looking Backward (1887). While Bellamy, from the imagined year 2000, had envisioned the harmonious collaboration of capital and labor under the benign directives of a social technocracy, Bierce grimly dissected the systemic dysfunctions that had tipped the American Republic into a fatal spiral.

"Battle of Kenesaw [sic] Mountain," Kurz and Allison print

As one of the few American writers with direct experience of battle in the Civil War, Bierce had earned his disillusionment honestly. By the 1880's volumes of personal and unit histories began to pour from the presses, justifying and magnifying the roles that individual soldiers and their regiments had played. But a handful of surviving veterans like Bierce, who was severely wounded in skirmishing before the battle of Kennesaw Mountain, wondered what was the meaning of the victory for which they and their generation had paid so dearly:

--Ambrose Bierce, "The Hesitating Veteran," 1888

Lieutenant Bierce, 9th Indiana Infantry

In "The Fall of the Republic" Bierce fiercely debunked the glorification of the War he had barely survived. But worse was yet to come: nostalgia for past glories would soon be replaced by popular longing for a future war—and any war would do. By the 1890's, opinion leaders like Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Cabot Lodge, and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. were promoting the notion of warfare as a way to make Americans a more virtuous, less materialistic, more unified people.[1]

Saint John the Baptist Preaching -- Mattia Preti (1613-1699) Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco

In the year 1842, in Meigs County, Ohio, Ambrose Bierce was born on June 24--the day venerated by many Christian traditions as John the Baptist's birthday. Though the agnostic Bierce would scorn an astrological connection to any saint, in Bierce's fierce criticism of the follies of the Gilded Age, is there not a reflection of the flame that raged in that fierce and uncompromising prophet? The cry of John in the wilderness: “You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the coming wrath?" would not have appeared out of place in Ambrose Bierce's editorials in the Wasp or the San Francisco Examiner.

Bierce in maturity

Bierce's response to Bellamy's utopian vision was sharp and immediate. An avid reader of Edward Gibbons The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire and a pessimist about the corrupting tendencies of democracy, Bierce saw no grounds for optimism about the American experiment. Bierce had defined the republican model of government in his Devil's Dictionary:

Republic, n. A nation in which, the thing governing and the thing governed being the same, there is only a permitted authority to enforce an optional obedience. In a republic the foundation of public order is the ever lessening habit of submission inherited from ancestors who, being truly governed, submitted because they had to. There are as many kinds of republics as there are gradations between the despotism whence they came and the anarchy whither they lead.[2]

Bierce's real fear was of government "of the people, by the people, and for the people"--which is to say, wrote Bierce upon quoting this "catching phrase" from Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, "was no government at all." The notion of self-government was self-contradictory, he wrote: "Government means control; it means limitation of the will of the governed by some power superior to himself." Looking back upon his own time from the 31st century, Bierce declared "It may seem needless at this time to point out the inherent defects of a system of government which the logic of events has swept like political rubbish from the face of the earth..." but Bierce nonetheless went on to catalog those defects in scathing detail, including the antagonism of Capital vs. Labor (in which contest Bierce assumed neutrality);and the delusion that "might makes right" (as reflected in the "long-discredited" principle of majority rule).

Bierce's short stories dealt not only with actual episodes of his years in the Union army, but also portrayed supernatural, macabre, and surreal situations which would retain their appeal in later centuries. Likewise, Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward has been categorized as a prototype of science fiction. In the climactic final chapter, Bellamy's narrator, Julian West, awakens (as he believes) from his dream / vision of the year 2000 to find himself in the familiar Boston of his own day--but with a radically different perspective on the social and economic inequities which had been systematically eliminated from the society of the future. "I have been in Golgotha," he attempts to explain to his fiancé and her mortified family, "I have seen Humanity hanging on a cross! ".

Photographer Lewis Hine (1874-1940) documented the pervasive exploitation of children in the mills, mines, and sweatshops of his era. Not until 1938 would this practice be abolished by the Fair Labor Standards Act. An earlier attempt to regulate child labor through Congressional power to control interstate commerce was rendered unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1918.

Americans of the 1880's became aware of the social inequities between the lives of rich and poor, if not always between black and white. or between men and women. By 1886 the republic was in the midst of the Great Upheaval--a series of 1,400 strikes that paralyzed the railroads and thousands of businesses. It was within this turbulent atmosphere that the Massachusetts lawyer-turned-newspaperman Edward Bellamy envisioned a better world--no longer a Gilded Age, but a utopian Golden Age. Born into a family of Baptist ministers, Bellamy's notes on the writing of his novel suggested that many Americans viewed the social inequities of their age with reactions foreshadowing revolutions of the twentieth century. "Not only are the toilers of the world engaged in something like a world-wide insurrection," wrote Bellamy in the postscript to Looking Back, "but true and humane men and women, of every degree, are in a mood of exasperation, verging on absolute revolt, against social conditions that reduce life to a brutal struggle for existence, mock every dictate of ethics and religion, and render wellnigh futile the efforts of philanthropy."

Laborers preparing cotton for the gin, near Charleston S.C. (1874) -- Courtesy of Library of Congress

Bellamy's novel was not mere utopian propaganda. Rather, it took the form of an engaging narrative of a young man who, like Rip Van Winkle (through the medium of an hypnotic trance gone awry), goes to sleep in the year 1887 and awakes to find himself in the year 2000. In the socialist utopia of the future to which Bellamy's protagonist, Julian West, is introduced by his guide, the means of production have been nationalized; poverty and want have been eliminated; and an "industrial army" controls the production and distribution of goods. Class conflict does not exist and even crime is made unnecessary. Though modern hindsight considers Bellamy's novel flawed in its premises and naive in its conclusions,[3] Bellamy's impulse to scrutinize and condemn the failures of his own age attracted thousands of readers and even sparked the emergence of dozens of "Bellamy Clubs" throughout the United States, organized to put his idealized notions into practice.

Bierce's diatribe against the failures of the republic was deeply at odds with Edward Bellamy's fantasy of a benevolent industrial socialism. [4] Yet both writers positioned themselves in an imagined future "looking back" at the republic of the 1880's to interpret the circumstances that had evolved from the distant present. And, like many Americans, both were not only mindful of the paradigm of the Roman republic but also troubled by the decline and fall of the empire into which that republic had devolved.

“The lesson of the war that should never depart from us is that the American people have no exemption from the ordinary fate of humankind. If we sin, we must suffer for our sins, like the Empires that are tottering and the Nations that have perished.” --Journalist and editor Murat Halstead, 1829-1908 [5]

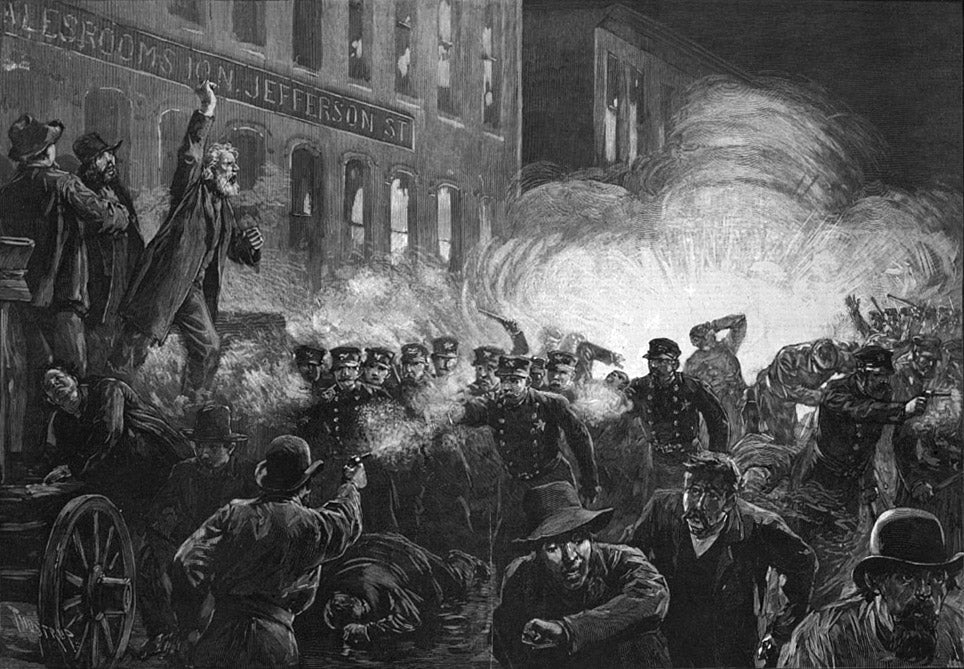

Unlike modern columnists with their measured dissection of political or social ills and reasoned suggestions toward treatment or cure, Bierce scorned any program of reform. However, the eerie finale to Bierce's essay foreshadowed confrontations which are all too real from today's perspective. The indelible image of Bierce's challenge to the irremediable wickedness of his age is the concluding paragraph of "The Fall"--which imagines an impending confrontation between police and strikers glaringly similar to that which had actually transpired in Haymarket Square in Chicago just two years prior to Bierce's writing. As the "hireling body-guards" defending the Capitol squared off against "sullen laborers with dynamite bombs concealed beneath their coats," there suddenly appeared, preceded only by rumors,

,...a tall, pale man clad in a long robe, bare-headed, his tresses falling lightly upon his shoulders, his eyes full of compassion, and with such majesty of face and mien that all were awed to silence ere he spoke. Slightly raising his right hand from the elbow, the index finger extended upward, he said in a voice ineffably sweet and serious: "As ye would that others should do unto you, do ye even so unto them." These words he repeated in the same solemn and thrilling tones three times; then, as the expectant multitude waited breathless for him to begin his discourse, stepped quietly down among them into their very midst, every one afterward averring that he passed within a pace of where himself stood. For an instant the crowd was speechless with surprise and disappointment, then broke into wild, fierce cries of "Lynch him! Lynch him!" and struggling into looser order started in mad pursuit. But each man ran a different way and the stranger was seen again by none of them.

Illustration by Alexandre Bida (1813-1895)

This paragraph is a direct parallel to the episode in Luke's gospel (4:14-30) in which Jesus returns to his hometown synagogue to proclaim the unwelcome message that God's blessings would be extended to the Gentiles. Jesus mysteriously eludes the mob reacting to this message: "They got up, drove him out of the town, and took him to the brow of the hill on which the town was built, in order to throw him off the cliff. But he walked right through the crowd and went on his way."

Just as Bierce had rejected the fundamentalist faith of his parents, he would also have shrugged off the mantle of prophet. But like Edward Bellamy he used the language of the gospels to evoke a warning echoing down to the 21st century. The crisis manifested on January 6, 2021 would confront defenders of the Republic with anarchists raging against electoral practices enshrined in the Constitution. Just as Bierce had traced the trajectory of republics proceeding from despotism to anarchy, he might have foreseen that the cycle of history was equally likely to revolve from anarchy into despotism. Bierce's aversion to democracy’s faults had perhaps blinded him to the perils of the forms of social and political domination which could emerge from the ashes of anarchy.

Yet Bierce’s parable of a messianic emissary attempting to mediate the conflicts of his own time did not rule out a way forward. A fundamental principle of nearly all societies and cultures, rooted in the instincts and traditions of reciprocity required by all mutual interactions, the Golden Rule voiced by that unearthly visitor could shine its light even upon the dire dilemmas of the first Gilded Age--or on our own. Such at any rate was the prophetic utterance of Ambrose Bierce, an unwilling prophet like Jonah of long ago who had also fled the divine summons.

The U.S. Capitol under siege during the insurrection of January 6, 2021. Does this eerie photo reflect Bierce's prophetic vision of the "Fall of the Republic?"

NOTES

[1] Of these three, only future Supreme Court Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (1841-1935) had ever seen combat. Commissioned a 1st Lieutenant in the 20th Massachusetts, Holmes participated in (and was wounded in) some of the most savage fighting in the eastern theater of the Civil War, including the battles of Ball's Bluff, Antietam, and Chancellorsville. While Holmes was eventually promoted to VI Corps staff in 1864, his friend and fellow officer Henry Livermore Abbott remained to command the 20th Massachusetts Regiment. Abbott, whose name is also found on the memorial wall at Harvard, was killed in the battle of the Wilderness in May, 1864.

[2] Ambrose Bierce, The Devil's Dictionary (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1993) p. 105. Compiled over several decades, the work was first published in 1906 as The Cynic's Word Book before publication as The Devil's Dictionary in 1911.

[3] See, for example, Looking Backward 1988-1888: Essays on Edward Bellamy (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988) especially Sylvia Strauss's essay "Gender, Class, and Race in Utopia."

[4] ""The Fall of the Republic" may be among the earliest of the many responses to and imitations of Bellamy's novel that appeared over the next several decades...The political views of the two writers differ so radically that one might be inclined to think that Bierce published his work when he did as a direct response to Bellamy." S.T. Joshi and David E. Schultz, editors, Ambrose Bierce: The Fall of the Republic and Other Political Satires (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2000), pp xi, xvii. Originally, says Bellamy in a postscript to Looking Backward, his narrator was to have awakened in the year 3000--the opening of the 31st century which was also Bierce's retrospective vantage point

[5] Murat Halstead,"The War Claims of the South: The New Southern Confederacy, with the Democratic Party as Its Claim Agency, Demanding Indemnity for Conquest, and Threatening A Disputed Presidential Election," An Address at Cooper Institute, New York, October 25, 1876. (Cincinnati: Robert Clark & Co. Printers, 1876).

The Bierce text referred to in this blog post is "The Fall of the Republic: An Article from a 'Court Journal' of the Thirty-First Century" San Francisco Examiner (March 25, 1888), reprinted in Ambrose Bierce: The Fall of the Republic and other Political Satires, (S.T. Joshi and David E. Schultz, editors (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2000), pp 102-113.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.