Caseyatthe.blog responds to "Know It All" at San Mateo Daily Journal

TO: Editor of “Know It All,” San Mateo Daily Journal / smdailyjournal.com

FROM: Rich Davis / Caseyatthe.blog

I took note of your recent mention of Ernest Thayer’s famous ballad:

At https://Caseyatthe.blog we appreciate all journalistic mentions of #CaseyattheBat because the immortal popularity of Thayer’s 1888 ballad is what drives our project!

But before the baseball historians or the College of San Mateo Bulldogs weigh in with their expert input, there are a few facts about the game of baseball that come into play. Neither Casey nor any other batter could strike out twice in the same at-bat. (Any batter can strike out more than once in the same inning, if his teammates "bat around" and bring him back to the plate, but in this particular inning, Thayer tells us Cooney and Barrows have both "died at first." Mudville has only one "out" left. To be fair, I think Mr. or Ms Know-It-All probably meant to say, “fanned at two pitches” meaning Casey swung but whiffed. But again we must set the record straight: in Thayer’s ballad, Casey certainly did not swing at those pitches. In fact, he “held up” or "laid off" as the sportscasters say—essentially he watched the ball go right by him. Twice he did that.

And those pitches at which Casey chose not to swing? The umpire called them “strikes” because, well, they were good pitches. They were “right in there” as the sportscaster reports—whether they were “up and in,” or “low and away,” or “right down the pike.” In Stanza VIII Close by the sturdy batsman the ball unheeded sped...suggests an inside pitch. Without even mentioning drop pitches of that day, or backdoor sliders or sinkerballs of today's game, the point is that the umpire judged the first two pitches came somewhere within the strike zone. And so he called “Strike one” and “Strike two.”

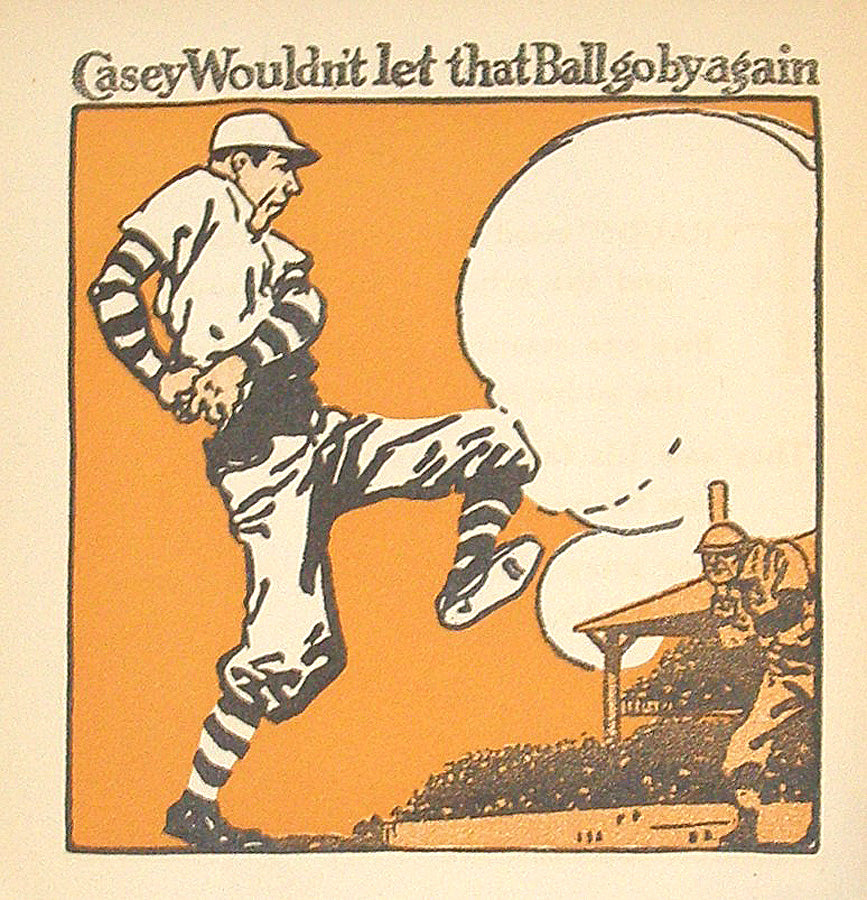

The hometown crowd emphatically disagreed with the umpire’s call. After the first called strike there were cries of “Kill him! Kill the umpire!” And that was no idle threat in the 19th century, when umpires were routinely threatened with bodily harm both from the bleachers and from the press. But this was a courageous umpire who was not easily intimidated. In fact, when Casey window-shopped the second pitch for "Strike two" the maddened crowd had to be quelled by Casey himself with a laudable display of forbearance. The Mudville partisans in Stanza XI stifled their shouts of “Fraud!” because they “...knew that Casey would not let that ball go by again.” Casey would not be “caught looking”--he was definitely going to swing at the next pitch.

What happened next is the stuff of legend. I would urge the Know-It-All team to re-read the ballad, because there is a lot more to learn from it than the mere perils of hero worship. In fact, "Casey" carries within it all the elements of Greek tragedy. Gilded Age America had little appetite for the ennobling catharsis of tragic drama but Thayer, in his sly, literary way was teaching his readers the wisdom of the ancients. "Phin" (Thayer's byline at the Examiner) was thoroughly grounded in the classics in high school and equally versed in the charms of traditional English and Scottish ballads as taught by Professor Francis Child at Harvard.

You are correct that Casey was "cocky" but he also personified courage, fortitude, competence, and the resolute exercise of his talents --the Roman paradigm of the classical hero. Romans--like Americans of Thayer's day--did not appreciate tragedy in the way of the worldly Greeks. But Thayer knew that baseball, like ancient warfare, must account for the human elements of hubris--excessive pride and ambition-- as well as hamartia--some deeply characteristic flaw--of the tragic hero. Though today's sportscaster jests after the called strike, "I bet he wishes he had that one back," we continue--even after 130 years-- to sympathize with Casey, his teeth "clinched in hate," wrestling with unfamiliar self-doubt and hearing beyond the clamor of the Mudville crowd the quiet footfall of fate.

Thanks again for your reference to "Casey at the Bat" and please accept the tutorial from https://Caseyatthe.blog in the constructive spirit with which it is offered!

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.