"Casey's" Companions and Counterfeits, Part II: The Classical Roots of Baseball Poetry

In previous posts "In Search of 'Casey's" Companions: A Tale of Two Clowns," and "In Search of the Counterfeit Casey," Caseyatthe.blog has explored the infancy of baseball balladry. Ernest Thayer, under the nickname that had followed him from childhood--"Phin"--was the pioneer of the emerging genre in America. After Thayer, every future contributor to the literature of baseball owed a debt to the Mudville slugger and his self-effacing creator.

But the link between "base ball," as it was first known, and the epic lore of the past was quarried from a deep literary vein. Thayer himself had been grounded in the classics at the Worcester Classical and English High School, then had immersed himself in the study of ancient English and Scottish ballads as taught by Professor Francis Child at Harvard. John Thorn, Major League Baseball's official historian, has traced the origins of "Base-Ball" back to 18th-century Britain, as illustrated in a book of children's verses by John Newbery, with a woodcut showing a ball, and bases, but not yet a bat (an implement that would evolve later).

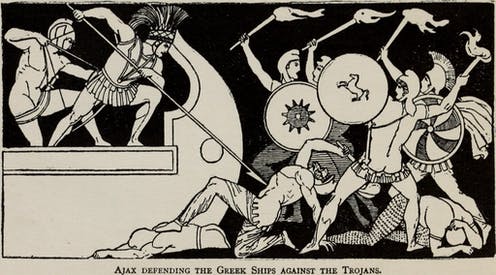

Like Ulysses, Thorn notes, Briton's imperial adventurers flew "over the main" in search of enterprise or treasure, but as in the children's game, and like Ulysses returning to Ithaca at the end of his perilous saga, the players returned triumphantly home. Indeed from the very origins of baseball poetry there was a strong connection to the epic themes of Western literature.

"In Search of the Counterfeit Casey" has identified what is likely the first of hundreds of "Casey at the Bat" spin-offs, parodies, sequels, or lampoons. The very first of these was falsely claimed for many years to have been the original. "Ansonius at the Bat," a versified account of a game played in 1889 at the Villa Borghese in Rome by Al Spalding's globe-trotting exhibition teams--only nine months after "Casey at the Bat" had first appeared in the San Francisco Examiner on June 3, 1888. Rediscovered and made public in 2020 by Caseyatthe.blog , the "Ansonius" poem had appeared in American newspapers in March 1889 while the Spalding teams still competed in France and England. "In Search of the Counterfeit Casey" tells the story of how the author of "Ansonius at the Bat" was advanced as the supposed "true author" of the original "Casey".

.

"Ansonius at the Bat" had employed some clear references to "Casey" (for example, its title!) but like most newspaper poetry contributors of that era the author had been provided no byline. Circumstantial evidence compiled by Caseyatthe.blog suggests the author was William R. Valentine, a young Irish poet working for the Sioux City Tribune, following a suggestion provided by his erudite roommate Frank J. Wilstach. "Ansonius," unlike the mythical Casey, was a real person, Adrian Constantine "Cap" Anson--whose career as the game's first superstar would land him (posthumously) in the Hall of Fame in 1939. The game played at the Villa Borghese in the Eternal City would inspire the Tribune writers to structure "Ansonius at the Bat" on the template of "Horatius," the 19th century's famous epic ballad about an ancient Roman hero, penned by British historian and parliamentarian Thomas Macaulay.

Unlike Ernest Thayer, who retained his anonymity as "Casey's" author for years after his ballad's sudden ascendance into American popular culture, Eugene Field by 1888 was already well-known, not only for his humor column Sharps and Flats in the Chicago Daily News but also for various books of children's poetry for which he is recognized today. "Little Boy Blue," like "Casey at the Bat," was first published in 1888, and other poems including "Wynken, Blynken, and Nod," and "The Duel" (otherwise known by its first line, "The gingham dog and the calico cat...") had already made Field a household name by the late '80's. But Field and his brother Roswell had loftier literary aspirations--based both on their classical training and their fascination with the luminaries of contemporary base ball.

Field family portraits including Eugene (on left), Eugene and his brother Roswell as youngsters, Roswell Martin Field, Sr., and their mother, Frances, who died in 1856. Roswell Field, Sr. was a well-known attorney who formulated the strategy which brought the Dred Scott case before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1856-1857.

What we know of the origins of the Field brothers' baseball poem comes from Eugene's friend, actor Francis Wilson, whose career in the musical theater of his day overlapped that of DeWolf Hopper. In an introduction to an 1899 edition of Echoes of the Sabine Farm, Wilson recalled a walk with Eugene on a wintry evening in 1890 in the Chicago suburb of Lake View. Wilson had offered to sponsor publication of one of Field's new works, and Eugene said that he and his brother "Rose" had worked on some playful translations of Horace's Odes, which poets since Rome's Augustan age had emulated, quoted, translated--or would grimly dissect, as did World War I poet Wilfred Owen with Horace's famous "Dulce e decorum est pro patria mori."

Francis Wilson (1854-1935) was an American actor, writer and producer who was a friend of Eugene Field. Like DeWolf Hopper, Wilson starred in productions of the McCaull Comic Opera Company in the 1880's. He was the founding president of the Actors' Equity Association.

Eugene had hoped to attach a biography of Horace to this volume of translations, but consented to print the "Odes" separately, beginning with a limited edition which would be circulated among friends and family. Eugene reluctantly set the biography aside, and would die in 1895 in his 46th year without completing it.

We know the Field brothers' translation of Horace circulated in various editions in the early '90's and continued to be published into the 20th century. It was titled Echoes from the Sabine Farm, a reference to the estate gifted Horace by his patron and benefactor Maecenas.

The location of Horace's Sabine Farm at the foot of Mount Lucretile has been identified based on Horace's descriptions of the site and landscape. As was expected by the Emperor, Horace bequeathed his villa to Augustus who was a friend, a recipient of his verses, and a generous benefactor.

Among the favorable reviews of Echoes was the following, from The Inland Printer:

"As a boy of ten, Mr. Field wrote letters in Latin to his father, and he has never lost his hold upon the language. But in making these sportive imitations, he has read Horace in the original, and all the translations he could lay his hands on...Mr. Field can be as frolicsome as old Horace....The New York Sun paragrapher always refers to Horace as 'the Eugene Field of Rome.'" (The Inland Printer Vol. IX, No. 7 [April 1892], p.583).

The last of the odes prior to the "Epilogue" was not a translation but rather an original poem, "At the Ball Game," which is quickly identified as a contemporary ballad written in Horatian mode. The table of contents attributes each of the odes to one or the other of the brothers--and "At the Ball Game" is attributed to "R.M.F." i.e. to Roswell Martin Field, Jr. (Roswell Sr. had died in 1869).

Here is the complete ballad, which we can now date properly to the period 1890-91, when "Casey at the Bat" (published in June, 1888) was still in its infancy, as was "Ansonius at the Bat," which first appeared in March 1889.

At the Ball Game

What gods or heroes, whose brave deeds none can dispute,

Will you record, O Clio[1], on the harp and flute?

What lofty names shall sportive Echo[2] grant a place

On Pindus'[3] crown or Helicon's cool, shadowy space?

Sing not, my Orpheus[4], sweeping oft the tuneful strings,

Of gliding streams and nimble winds and such poor things;

But lend your measures to a theme of noble thought,

And crown with laurel these great heroes, as you ought.

Now steps Ryanus forth at call of furious Mars[5],

And from his oaken staff the sphere speeds to the stars;

And now he gains the tertiary goal[6], and turns,

While whiskered balls play round the timid staff of Burns.

Lo! from the tribunes[7] on the bleachers comes a shout,

Beseeching bold Ansonius to line 'em out;

And as Apollo's[8] flying chariot cleaves the sky,

So stanch Ansonius lifts the frightened ball on high.

Like roar of ocean beating on the Cretan cliff[9],

The strong Komiske gives the panting sphere a biff;

And from the tribunes rise loud murmurs everywhere,

When twice and thrice Mikellius beats the mocking air.

And as Achilles' fleet [10]the Trojan waters sweeps,

So horror sways the throng,—Pfefferius sleeps!

And stalwart Konnor, though by Mercury[11] inspired,

The Equus[12] Carolus defies, and is retired.

So waxes fierce the strife between these godlike men;

And as the hero's fame grows by Virgilian pen[13],

So let Clarksonius Maximus be raised to heights

As far above the moon as moon o'er lesser lights.

But as for me, the ivy leaf [14]is my reward,

If you a place among the lyric bards accord;

With crest exalted, and O "People," with delight,

I'll proudly strike the stars, and so be out of sight.

-- Roswell Martin Field, in Echoes from the Sabine Farm (Kindle Edition). Introduction by Francis Wilson. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1896 edition. (Limited private editions were published as early as 1890-91).

References in "At the Ball Game" to ball players, together with their teams during the 1888-1891 period, and date if elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame (HOF)

Jimmy Ryan (Ryanus), Chicago White Stockings / Chicago Pirates , center fielder

Adrian Constantine "Cap" Anson ("Ansonius"), Chicago White Stockings, first baseman HOF 1939

Thomas Burns, ("Burns"), Chicago White Stockings, third base / shortstop

Charles Comiskey ("Komiske"), St. Louis Browns / Chicago Pirates, manager and first base-HOF 1939

Mike "King" Kelly ("Mikellius"), Boston Beaneaters / Boston Reds, outfielder, catcher, and manager HOF 1945

Fred (Nathaniel Frederick) Pfeffer ("Pfefferius"), Chicago White Stockings, second base

Roger Connor ("Konnor"), New York Giants, first and third baseman HOF 1976

Fred Carroll ("Carolus"), Pittsburgh Alleghenys and Pittsburgh Burghers, catcher and outfielder

John Gibson Clarkson ("Clarksonius Maximus") ,Boston Beaneaters, pitcher HOF 1963

Cap Anson and Fred Carroll had appeared both in the 1889 "Ansonius at the Bat," and like Jimmy Ryan, Thomas Burns, and Fred Pfeffer cited in "At the Ball Game" had also traveled with Al Spalding's globe-circling baseball tour in 1888-1889.

"At the Ball Game" did have a run of popularity through the 1890's, attributable to Eugene Field's prolific versification which kept his books in print long after his untimely death in 1895. Newspaper readers in the '90's often referred to "Casey at the Bat" as Eugene Field's masterpiece, but this misconception was likely based as much on imperfect recollections of "At the Ball Game" as on the fact that Ernest Thayer was not discovered by DeWolf Hopper as the true author of "Casey" until 1892. Even after that, Thayer remained reluctant to assert his authorship until it was challenged more aggressively in 1904-1905 by journalist and theatrical promoter Frank Wilstach.

Regarding the poetic merits of "At the Ball Game," I will defer to John Thorn, MLB's official historian, and to poet and translator A.M. Juster (who has written the definitive essay on "Casey at the Bat" ( see "'Casey at the Bat' and its Long Post-Game Show" ) and has also translated the satires of Horace. However, from the viewpoint of Caseyatthe.blog , the Roswell Martin Field poem would have seemed much more clever in the 1890's than at any time thereafter -- mainly because the players so prominently displayed in the text would eventually begin to fade from the memory and affection of fans. A Collier's writer in 1911[15], in an article on baseball poetry circulated on the Exchange, fondly recalled the "mock-heroics" in the Field brothers' verses, but added that while Clarkson and his companions "are not forgotten today, a new generation sits on the bench and mainly on the bleachers" and that Clarkson's eminence had already been surpassed by that of Christy Mathewson.

John Clarkson (1861-1909) retired from the game as the winningest pitcher in National League history -- although his production had declined when the pitcher's rubber was moved in 1893 to 60' 6" from the back of home plate. On June 4, 1889, Clarkson became the first pitcher in major league history to strike out 3 batters on 9 pitches, in a game vs. the Philadelphia Quakers.

The titular eminence of Cap Anson in the 1889 "Ansonius at the Bat" had by 1891 already been surpassed by that of John Gibson Clarkson: "As far above the moon as moon o'er lesser lights" according to the author of "At the Ball Game." Clarkson's pitching dominance at the end of the 1880's was no doubt foremost in the mind of the Field brothers in Chicago, who had witnessed the contracts of both "King" Kelly and then Clarkson sold by the White Stockings to the Boston Beaneaters for $10,000 apiece in 1887 and 1888, respectively. With the gloom familiar to any fan who has seen his or her favorites traded to a rival team, Eugene and Roswell Field had suffered the reporting of Clarkson's 33-win season for the Beaneaters in 1888, followed by an even more astounding 49-19 record in 1889, winning pitching's Triple Crown by leading the National League in wins, ERA and strikeouts.

The drama of the contest portrayed in "At the Ball Game" does not come close to that of either of its predecessor ballads. "Ansonius at the Bat" followed the action of "Casey at the Bat" very closely (though "Ansonius," unlike Casey, slugged the ball out of the park, depriving its readers of Thayer's tragic catharsis). Instead, "At the Ball Park" is structured mainly as a showcase for the great names of the era. The game appears to end in lines 23 and 24 when stalwart "Konnor" (Roger Connor) attempts to steal home but is put out by indomitable Fred Carroll ("Carolus"), catcher for the Pittsburgh Alleghenys. (Carroll was no slouch at the bat, either, in 1889 leading the National League in on-base percentage [OBP] as well as in on-base percentage plus slugging [OPS]).

What is beyond doubt is that "At the Ball Game" displays a debt to both predecessor ballads in its attempt to surpass them. Roswell Field tried to out-do both "Casey" and "Ansonius" with classical references, but without the dramatic impact of either forerunner. Notably, the simile used by Field in line 17 "Like roar of ocean beating on the Cretan cliff" is a direct borrowing from Thayer's "...beating of the storm waves on a stern and distant shore" (stanza IX). The narrator of "At the Ball Game" inserts himself at the end of the poem to appeal somewhat abjectly for the ivy leaf and for a place among the "lyric bards" of baseball verse, who at that time and thereafter would acknowledge the preeminence of Ernest Thayer --even in his self-imposed near-anonymity--among his peers in the Elysian Fields. And most astoundingly, it was "The Mighty Casey"--a mythical figure whose flawed character and tragic renown would outlive the narratives of the actual ballplayers of the late 19th century--who would be lifted to Olympian heights by the newspaper readers, vaudeville (and then radio) audiences, base ball aficionados, and generations of school-children from that day to this.

What is notable about Roswell Field's "At the Ball Game," though, is the deliberation with which Roswell and Eugene put together a truly all-star Nine to represent the game to posterity as played in their own generation. The Baseball Hall of Fame would not begin to admit members until 1936 -- but the Nine chosen by Roswell and Eugene Field contained FIVE future Hall-of-Famers -- Anson, Comiskey, Kelly, Connor, and Clarkson. It was an age in which players often filled multiple roles in various positions, but the Field brothers assembled a stellar line-up of outfielders and infielders who would have been welcomed into any All-Star team of their decade. As for catcher, the brothers chose steady Fred Carroll, who holds the record for pitchers aged 24 in on-base plus slugging (OPS) percentage, with .970, set in 1889. Bill James in Baseball Abstract considered Carroll the "best young catcher before Johnny Bench."

Fred Carroll (1864-1904), Pittsburgh Alleghenys. Carroll played on the 1888-1889 Spalding World Tour, and is referred to as the "best young catcher prior to Johnny Bench."

And who could fault the selection of John Clarkson of the Boston Beaneaters, formerly of the Chicago White Stockings--one of the best pitchers of his era? Teammate Fred Pfeffer characterized Clarkson as the "master of control." He won 30 or more games in the season six times!

Finally, the Field brothers chose Charlie Comiskey, whose nickname would become "The Old Roman," long before his legacy would become associated with Chicago as the founding owner of the White Sox (Comiskey did play in 1890 in the short-lived Players' League with the Chicago Pirates). Though Comiskey was known as a competent first baseman for the St. Louis Browns, I'd like to think the brothers selected Comiskey for their immortal Nine based on his managerial prowess as much as for his play at first base. During the 1884-89 period, as a player / manager, Comiskey led the Browns to four consecutive championships of the American Association -- and a respectable runner-up finish in 1889.

Hindsight vs. Foresight

Of course there were other candidates qualified for inclusion in the Field brothers' pantheon of great ball players of the 1880's and '90's--but who are missing from this lineup. These included catcher Moses Fleetwood Walker, who with his brother Weldy played for the Toledo Blue Stockings in 1884--becoming the first African-American players in the major leagues prior to Jackie Robinson. Playing for the Newark Little Giants in 1887, Moses Walker caught for George Washington Stovey, considered to be the best African-American pitcher of the 19th century. Stovey and Walker sat out an exhibition game against the White Sox on July 14, 1887, when it was reported that Cap Anson objected to playing against them on the basis of their race. The New York Giants had targeted the purchase of contracts of both Stovey and Walker in that same year, but that deal was not concluded--because Newark was not interested in the sale.

Moses Fleetwood Walker (left) and George Washington Stovey--famed battery for the Newark Little Giants. After helping his University of Michigan team to a 10-3 record in 1882, Walker became in fact the first African-American to play in the major leagues. But the shameful color barrier adopted by the leagues in 1889 would persist until Jackie Robinson stepped onto Ebbets field in Brooklyn in 1947.

And we should not forget Ulysses Franklin "Frank" Grant--star second baseman in the International League in the 1880's with the Buffalo Bisons. A powerful hitter in spite of his small stature, and renowned for his defensive skills, Grant would neither make it into the Major Leagues nor into the Field brothers' legend, but he would in fact arrive in the Baseball Hall of Fame in the 21st century, elected in 2006.

Frank Grant (1865-1937) was arguably the best African-American player of the 19th century. He was voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

Frank Grant (1865-1937) was arguably the best African-American player of the 19th century. He was voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

So in resurrecting their long-lost baseball ballad, let us recognize the poets and translators Roswell and Eugene Field not only for their classical erudition, but also for their well-honed baseball instincts and for their selection (though imperfect and incomplete) of a baseball Nine which they believed could hold its own in any competition -- whether within their own century or upon the timeless diamonds of the Elysian Fields! From our own distant perspective, we may imagine such a place out of time where players of every decade and of all races would take the field--where George Stovey could strike out Cap Anson, and where Frank Grant could hit a home run over Jimmy Ryan's outstretched glove. Perhaps within the celestial precincts, all will compete fiercely and amicably for the love of the sport at which they once excelled on this imperfect sphere.

Notes

[1] Clio (or Kleio ) was the ancient Greeks' Muse of History.

[2] In Greek mythology, Echo was a nymph of Mount Cithaeron, who figured in the story of Narcissus.

[3] Pindus refers to a mountain range in Northern Greece; Mount Helicon also is celebrated in Greek mythology as the site of two springs sacred to the Muses.

[4] Orpheus was a renowned musician, poet, and prophet in Greek religion.

[5] Not only was Mars the Roman god of war, but he was considered a pater of the Roman people. His Greek counterpart, Ares, was a more destructive and unpredictable force than Mars.

[6] Tertiary goal = third base

[7] The Roman tribunes represented the plebeians. The tribune was the first office of the Roman state that was open to the plebeians, who were freemen usually employed in the trades, laboring to pay taxes to support the patricians. The tribunes were charged with defending the interests of the plebeians, able to use the power of veto over actions of consuls and magistrates.

[8] Apollo--a complex, multivalent deity-- was one of the principal figures of both Greek and Roman religions. Apollo is recognized as the god of music, poetry, dance, healing, truth, prophecy, the sun (hence, "Apollo's flying chariot") and light.

[9] Cf "Casey at the Bat," stanza IX, "...Like the beating of the storm-waves on a stern and distant shore."

[10] Achilles' fleet refers to the ships of the Achaeans, who in the Iliad have landed in the Hellespont to besiege the city of Troy. Achilles was recognized as the greatest of the Greek warriors; his rage at the appropriation by King Agamemnon of his beloved war-prize, Briseis, is the motive driving Homer's saga.

[11] While in the Roman pantheon, fleet-footed Mercurius had a diverse portfolio including oversight of trade, transport, thieving and trickery, he is more commonly identified now with the Greek's Hermes, the messenger of the gods. The attribute referred to in this stanza is "speed."

[12] This is more likely intended as "eques" or "knight," rather than "equus" = "horse".

[13] Virgil, a friend and contemporary of Horace, is considered the greatest of Roman poets, and is the author of the Roman national epic, the Aeneid, which has had a lasting influence on Western literature.

[14]The "ivy leaf" here symbolizes eternity, perennial life, and immortality.

[15] "Baseball Poetry," in Collier's, reprinted in Mt Sterling (Kentucky) Advocate, November 8, 1911.

#CaseyattheBat #BalladoftheRepublic

Frank Grant (1865-1937) was arguably the best African-American player of the 19th century. He was voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

Frank Grant (1865-1937) was arguably the best African-American player of the 19th century. He was voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.