In Search of "Casey's" Companions: "A Tale of Two Clowns"

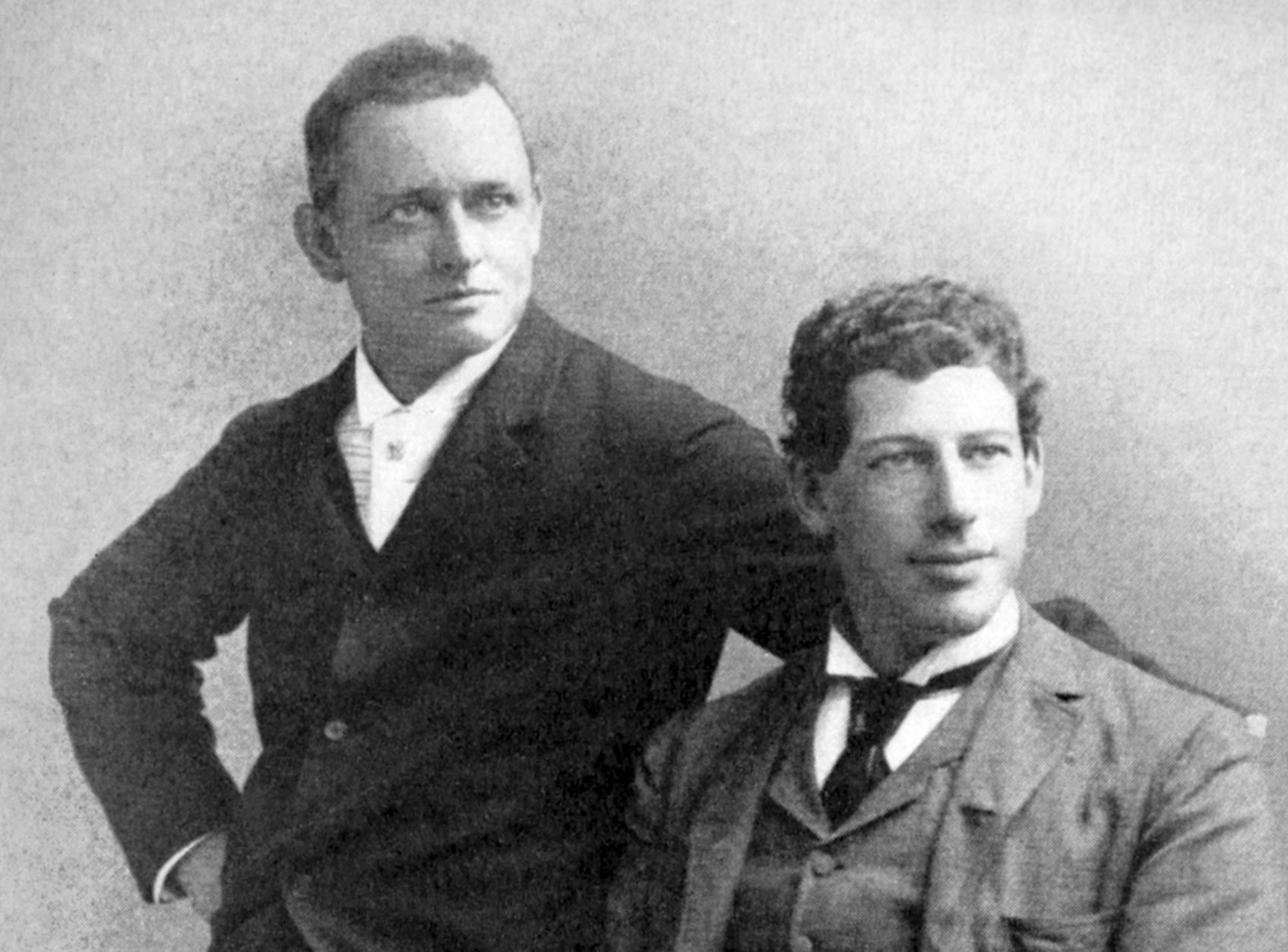

The dedicated sleuthing of MLB's official historian, John Thorn, has brought to light a "companion piece" to "Casey at the Bat," dating to October 1889--the month in which the New York Giants won the World Series in a crosstown shootout, defeating the Brooklyn Bridegrooms (the future Dodgers) six games to three. Thorn presented his findings in a January 6 post to his "Our Game" blog, entitled "A Tale of Two Clowns." The two clowns in question were DeWolf Hopper and fellow baseball crank Digby Bell--both renowned players in vaudeville and musical theater of the late 19th and early 20th century. Hopper's autobiography was subtitled "Once a Clown, Always a Clown."

Once a Clown Always a Clown, (1927) DeWolf Hopper's autobiography

Caseyatthe.blog presents Thorn's engaging article below, just as it appeared this month. But first we'll venture a few comments.

This post will be the first of several in which we will explore both Casey's "companions" as well as his "counterfeits"-- the culmination of years of research into the first baseball poems to find their way into American culture.

Thorn rightly notes that many of Ernest Thayer's contemporaries grasped the close resemblance of the "Ballad of the Republic" (Thayer's subtitle) to the epic saga of "Horatius," by Thomas Babington Macaulay. As outlined elsewhere in this blog (see "Why the Ballad of the Republic," October 30, 2019) , "Casey" should be understood as Thayer's brilliant misprision--a "creative misreading"-- of Macaulay's 1842 ballad. Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome--which contains "Horatius" and other battle-poems--was one of the best-selling books of the 19th century both in Britain and in America. "Horatius" was particularly popular with the generation of Americans born in the 1840's who would fight the Civil War. Ohio Colonel Dan McCook notably inspired his brigade with lines from "Horatius" as they stood to arms before the battle of Kennesaw Mountain.

We know that Thayer and his classmates at the Classical and English High School in Worcester grew up both hearing and participating in recitations of "Horatius" --just as my generation memorized and recited "Casey." Thorn is right that Thayer had a bone to pick with Macaulay--and with his iconoclastic humor (which classmate and Lampoon contributor George Santayana claimed to share) young Ernest turned Macaulay's rollicking Roman triumph into a Mudville tragedy.

Page from physician Arthur Bloomfield's 1954 monograph comparing the texts of "Horatius" and "Casey at the Bat"

The Arthur Bloomfield monograph [1](1954) comparing "Horatius" and "Casey," cited by Thorn, is one of the rarest items in what Martin Gardner referred to as the "Casey canon." A renowned California physician, Bloomfield (1888-1962) cited several of the obvious likenesses between the two ballads--though he missed others. By the mid-20th century, Macaulay's verses were (especially in America) "more admired than read"--a backhanded compliment once applied to Milton's poems. But from Thayer's time on, scholars, poetry lovers, and practitioners of the dramatic arts (like DeWolf Hopper) were convinced that the dramatic framework of "Casey at the Bat" was constructed on a specific classical model.

As Hopper famously opined regarding "Casey," There is no day in the playing season that this same supreme tragedy, as stark as Aristophanes for the moment {emphasis mine} does not befall on some field." Hopper should have known that Aristophanes was the Greeks' most famous comic--not tragic-- dramatist, but he may have had it right after all. It was Aristophanes to whom Plato attributed the sublime dramatic insight, often quoted by Churchill: "The qualities required for writing tragedy and comedy are the same, and a tragic genius must also be a comic genius."[2]

Aristophanes (ca 450 - ca 388 BC), Athenian playwright often called the "Father of Comedy"

One last note before presenting Thorn's "Tale of Two Clowns. " John Thorn adds, after his review of the evidence linking "Horatius" and "Casey:"

For me, the takeaway is that Thayer’s poem is literary — that is, written to be read, whether or not it was ultimately to be performed."

On this one point--and this point only--I dare to disagree with Thorn. "Casey at the Bat" was in fact written to be declaimed--whether or not it was to be read! Hopper's genius, and the source of his undying connection to the saga of "Casey," was his recognition of this fact. Hopper's career-long performance of "Casey" --constantly demanded by Hopper's audiences, even when (as the evidence shows) Hopper occasionally tried to unshackle himself from his alter ego.

For "Casey," just like the saga of his predecessor "Horatius," was from the beginning deeply rooted in the oral tradition of tales and ballads studied and taught by Francis J. Child. As Harvard's first professor of English, Child collected and published the ancient folk ballads of England and Scotland. Thayer's Harvard classmates considered Child the most significant influence on Thayer's poetic style and creativity. In this way, "Casey" owes a significant debt to the spare, unsentimental narratives of the English and Scottish ballads which Thayer learned from Child. From antiquity, these ballads were set to music by poets and minstrels, as referenced in Thayer's subtitle "A Ballad of the Republic, Sung in the Year 1888." And oddly, like the anonymous folk ballads collected by Professor Child, "Casey at the Bat" sprang into American culture seemingly without an author--its origin identified (if at all) only by the cryptic pen name "Phin."

Harvard College's first Professor of English, Francis J. Child (1825-1896), Harvard College Class of '46. Thayer learned the history and art of the folk ballad in Child's class. Courtesy U.S. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division (public domain).

[1] Bloomfield, Arthur L. (1888-1962) Horatius at the Bridge & Casey at the Bat. San Francisco: Grabhorn Press, undated. Private folio printing (75 copies) for presentation to the Roxburghe Club, a society of bibliophiles who have met since 1928 in San Francisco. The original Roxburghe Club was formed in England, dating to June 1812 when the enormous library of the late Duke of Roxburghe was put up for auction. Both the San Francisco and English clubs continue to be active.

[2] William Manchester, "Preamble," to The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill: Visions of Glory, 1874-1932 (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1983 Hardcover edition), pp. 28-29.

A Tale of Two Clowns: Digby Bell’s lost companion piece to “Casey at the Bat”-- from "Our Game" blog by MLB official historian John Thorn

“Casey at the Bat” is an American classic, and deservedly so. When it made its public debut on August 14, 1888, its author was unknown and it had been read only by those who happened to purchase the San Francisco Examiner on June 3 of that year, its only appearance in print. The man who made “Casey” a sensation on Broadway and then across the nation was not the poet, later to be revealed as Ernest Lawrence Thayer, but instead a comic actor named DeWolf Hopper.

Another comic actor — Hopper’s best friend, baseball tutor, and collaborator in many light-opera productions — was Digby Bell. Only one year later — at another baseball-themed evening — Bell, equally fond of baseball monologues, first offered up a ditty penned for him by fellow actor George Marion. Over the ensuing decades it became known as “The Tough Boy on the Right Field Fence,” but several variations of that title appeared in print: the boy was sometimes called a kid; the fence was sometimes located in left field. On October 20, 1889, when the theater set’s “High and Mighty Order of Baseball Cranks of Gotham” honored the National League champion New York Giants, singers and comics and banjoists took their turns entertaining the audience, especially the Giants’ players and officials. The New York Evening World reported:

Though every artist received a double encore, the hit of the evening was made by Mr. Digby Bell. That wonder first sang a little ditty about a potato and an acorn in an inimitable way, and then responded to an encore by reciting a new and original poem entitled “The Tough Boy on the Polo Fence,” the lines of which probably contained more baseball parlance and popular slang to the square inch than any ever written before.

DeWolf Hopper, of course, met with a rousing reception, and after singing verse after verse about a man who mismanaged a calcium light, he was finally obliged to recite the poem he has made famous, “Casey at the Bat.”

Today “Casey” is known by all baseball fans, many of whom learned as children to recite whole verses from memory. It is a fixture in the firmament of American popular verse. Yet the lines of “Tough Boy” were never anthologized so today its charm seems beyond recapture.

Why had it fallen into oblivion, I asked, and what was Bell’s monologue all about, anyway? How could a poem once thought the equal if not the superior to “Casey” have so utterly disappeared?

***

Thayer was revealed as Casey’s creator a few years after Hopper’s recital. A literary gent, he had studied philosophy at Harvard, graduated magna cum laude, and served as editor of the Lampoon. Its business manager for a time was William Randolph Hearst who, after expulsion from Harvard, was given the editorship of the newspaper his father had just purchased, The San Francisco Examiner. Hearst invited Thayer to contribute a humor column, which he did, under the name “Phin,” for the better part of two years. On June 3, 1888, The Examiner published Phin’s final effort, the rollicking ballad soon to be known across the land as “Casey at the Bat.”

Yet “Casey” might have vanished without a trace, like Phin’s other five-dollar ditties, except that novelist Archibald Clavering Gunter clipped it from the paper and kept it with him on his next trip east. On August 14, 1888, at Wallack’s Theatre in New York, he was backstage before a performance of Prince Methusalem, a Johann Strauss operetta given as a “complimentary testimonial” to the New York Giants and visiting Chicago White Stockings. One of the stars of the evening was DeWolf Hopper, a regular attendee at the Polo Grounds who wanted to supply some diversion with a baseball theme to spice things up. Gunter gave Hopper the poem that afternoon, Hopper proved a quick study, and between acts of the comic opera he recited “Casey at the Bat.”

The audience loved it. In his autobiography, Once a Clown, Always a Clown, Hopper got the date of Casey’s debut wrong, placing it in May (before Thayer had even written it), but captured its effect on the audience:

On his debut Casey lifted this audience, composed largely of baseball players and fans, out of their seats. When I dropped my voice to B flat, below low C, at ‘the multitude was awed’ [the poem in fact reads: “the audience was awed”], I remember seeing Buck Ewing’s gallant mustachios give a single nervous twitch. And as the house, after a moment of startled silence, grasped the anticlimactic denouement, it shouted its glee. . . . They had expected, as any one does upon hearing Casey for the first time, that the mighty batsman would slam the ball out of the lot, and a lesser bard would have had him do so, and thereby written merely a good sporting-page filler.

Hopper would continue to recite “Casey,” by his estimate, some 10,000 times over the next four decades. That the poem appeared in countless anthologies, too, was testament not to Hopper’s stentorian styling (preserved for the ages; http://bit.ly/2N0AeuR), but to Thayer’s genius and gift for parody.

The resemblance of “Casey at the Bat” to Thomas Babington Macaulay’s “Horatius at the Bridge” was noted early on (“F.J. Wilstach Casts Light on the Question of Authorship,” Washington Post, December 18, 1904). Fifty years later, Arthur Leonard Bloomfield wrote, “Thayer probably hated memorizing Horatius in prep-school, and how he must have enjoyed taking it out on Casey!”

Others have argued that Casey’s resemblance to Horatius is scant. For me, the takeaway is that Thayer’s poem is literary — that is, written to be read, whether or not it was ultimately to be performed.

Hopper may have ad libbed a line or two to suit an audience, but he never strayed far from the text. Bell, on the other hand, varied the text from one appearance to the next, with the result that no single version endured. In 1894, he went so far as to tell a reporter that he did not wish it ever to be published; by keeping it “hidden,” he claimed, “The Tough Boy” would be “always fresh and attractive to the public, whenever he would recite it, unlike ‘Casey,’” which “soon ran out” after it began to appear in the newspapers.

Bell miscalculated — or he may have correctly assessed that “The Tough Boy” was more a performance piece than a ballad of the republic, as “Casey” was subtitled and has proven to be. A sense of Bell’s delivery may be had from a 1909 recording of the poem, but by then most of the original lyric of 1889 had been truncated or replaced (http://bit.ly/39I3Gzy). The Edison Phonograph Monthly praised its “realistic baseball talk indulged in by the youngster from a ‘deserved’ seat on the right field fence. He tells the home team how to play the game and what he thinks of them when their playing isn’t up to his standard.”

Bell’s affected brogue makes transcription of the recording difficult, but below I offer a preliminary compilation from various newspaper reports of “The Tough Boy on the Right Field Fence.”

The Tough Boy on the Right Field Fence

Dere was twenty t’ousand folks inside,

De crowd was just immense,

Bill Mooney, Shorty Burns an’ me

Were outside of de fence.

Shorty he clim up on a tree,

Jest over where I kneeled

A-peekin’ t’rough the fence wid Bill,

A-takin’ in de field.

De game was even — two and two,

New York was at de plate —

T’ree men on bases, two men out,

T’ree balls, two strikes — dat’s straight.

De Cincinnaty pitcher took

De ball; I held my breat’,

He spat twice on his han’s and twirled,

De crowd sat still as deat’.

De batter banged, de ball flew up

Ex if fired from a gun;

De crowd riz up an’ give a yell —

It looked like a home run.

Up in de sky to center field

De ball sailed — Hully, Gee!

I dasen’t wink. I glued my eye

Clos to de fence to see.

An’ Shorty stood up on er branch

An’ let go both his han’s;

Branch broke, or somethin’, Shorty drapped

An’ top o’ me he lan’s.

Dat’s all I know — de next I knowed

I’m lying here in bed —

Say, tell me, doc, is my back broke?

An’, say, is Shorty dead?

I ain’t afeered to know de wust —

Will I always be lame?

But — break it to me gently, doc,

Ef New York lost dat game.

Additionally:

Dere goes a sky scraper [a high fly ball — jt];

Well, dat’s a dead bird, you kin bet.

Well, if th’ mush didn’t muff it!

Why don’t he telephone for a net?

Good boy; run! run;

A-a-h, go back an’ warm yer face!

If I was th’ captain of your team

I’d give you the razoo chase;

You’d want er sheriff an’ a search warrant

To go out an’ find first base.

Git ’em over de plate.

Strike? Dat empire’s a dead skin.

It ain’t no use talkin’,

W’en he’s de Solomon our boys can’t never win.

That’s a bute! Git up an’ run;

Run, you son of a gun! run!

Foul? Chee, but dat empire is makin’ us dance.

I’d like to have a boot flirtation wid de seat of his pants.

Play ball! Play ball! W’y he couldn’t hit a growler,

An’ if he did he’d flounder in the foam.

Ah. wot did I tell yer? Dat settles it.

Our name is mud, and here’s de wizard dat’s going home.

Rats. Rats! Say, who told youse sons of guns dat yuse could play ball?

Why if I was a Wanderbilt I’d have baseball for every meal.

I’d sit at the table and I’d play ’em early and late,

And when they were out doing their pretties

I’d be putting codfish balls over the plate.

--by Digby Bell, 1889

#CaseyattheBat #DeWolfHopper #DigbyBell #Caseyatthe.blog #BalladoftheRepublic @thorn_john @stocktonports @mlblondonseries @mlbuk @MLBUKCommunity @baseball_ref @SABR @baseballhof #BalladoftheRepublic @OnlyAGameNPR @SBNation @MartinKessler91 @klgiven @PawSox @PolarPark2021 @SBHistoryMuseum @worcestermag @tgsports @PulpEphemera @baseballminutia @BBHistoryDaily @nut_history @RedSox @DickFlavin @SportLiterate @NYY_Report @InthePastLane @PaineProfitt @ClaytonTrutor @HofDigital @MattBaseballGB @archivesfdn @sfchronicle @radio_worcester @Worcester_PL @BaseballAmerica @Dingerball1 @TweetWorcester @DrPaulRSem @SFpubliclibrary @SmithsonianMag @BaseballAmerica @TheAmHistorian @PoetryFound @poetrymagazine @redreporter @MitchNathanson @baseballireland @RCollinsDavis

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.