In his final 1887 ballad for the San Francisco Examiner, Ernest Thayer abandoned his variations on the absurd complexities of the love triangles which had been his constant theme since September. He returned to a vein he had mined since Lampoon days at Harvard--the impossibility of heroism in the modern age. The last of the known Thayer contributions to the Examiner in 1887 was A Sea Ballad: Thrilling Account of an Incident in American Navy Life published on December 4. This darkly comic ballad (directly referencing W. S. Gilbert's Bab Ballads with shades of H.M.S. Pinafore) contains multiple subtitles, including " "THE HEROIC CAPTAIN;" and "Something Which Will Make the Hearts of American Citizens Glow With Pride." Thayer was formulating something he wanted to say either to, or about, the American Republic of 1887.

"Casey's" First Draft: Song of a Captain Bold

Yes, this is a sea ballad, not a baseball ballad. And in its form and setting, it has more in common with Gilbert and Sullivan's H.M.S. Pinafore than to an epic baseball showdown. But on closer inspection we'll recognize familiar elements: a bold, extravagant act, ventured by a protagonist obsessed with his own legendary status, before a spellbound audience, concluding with a tragic twist in Thayer's unique mode. Aren't these among the same features that have long evoked our fond remembrance and endless re-tellings of "Casey at the Bat?"

I submit that "A Sea Ballad" was essentially Thayer's first draft of "Casey."

W. S. Gilbert (drawing as "Bab") illustration from "The Yarn of the Nancy Bell" in The Bab Ballads

A Sea Ballad

Thrilling Account of an Incident in American Navy Life

The Heroic Captain.

Something Which Will Make the Hearts of American Citizens Glow With Pride

The author of this little ballad has long and ardently desired to immortalize in song an American naval officer of the present generation, but as the dove of peace seems to have permanently roosted on this country, and as the events of the last few years have yielded no material for sea verse of an heroic nature, the author is fain to content himself with a fictitious but not altogether improbable incident. He does not expect that his little yarn will Immortalize anybody.

Oh, list to the moan of a toothless gale,

Of a gale too weak to roar,

And hark to the swash of the waves that wash

A pleasant, sandy shore.

For I sing a song of a captain bold,

More bold than tongue can tell--

Much bolder than he whose name we see

In the yarn of the Nancy Bell.

I am sure my hero was very brave,

And a trifle reckless, for

The venturesome man he sailed in an

American man-of-war.

And he took his ship many miles from land

Where the water is deep and cold;

All honor be to him, for he couldn't swim,

Could not this Captain bold.

He could saw a board and stop a leak,

And mend anything that broke;

He could patch a sail and drive a nail,

But he couldn't swim a stroke.

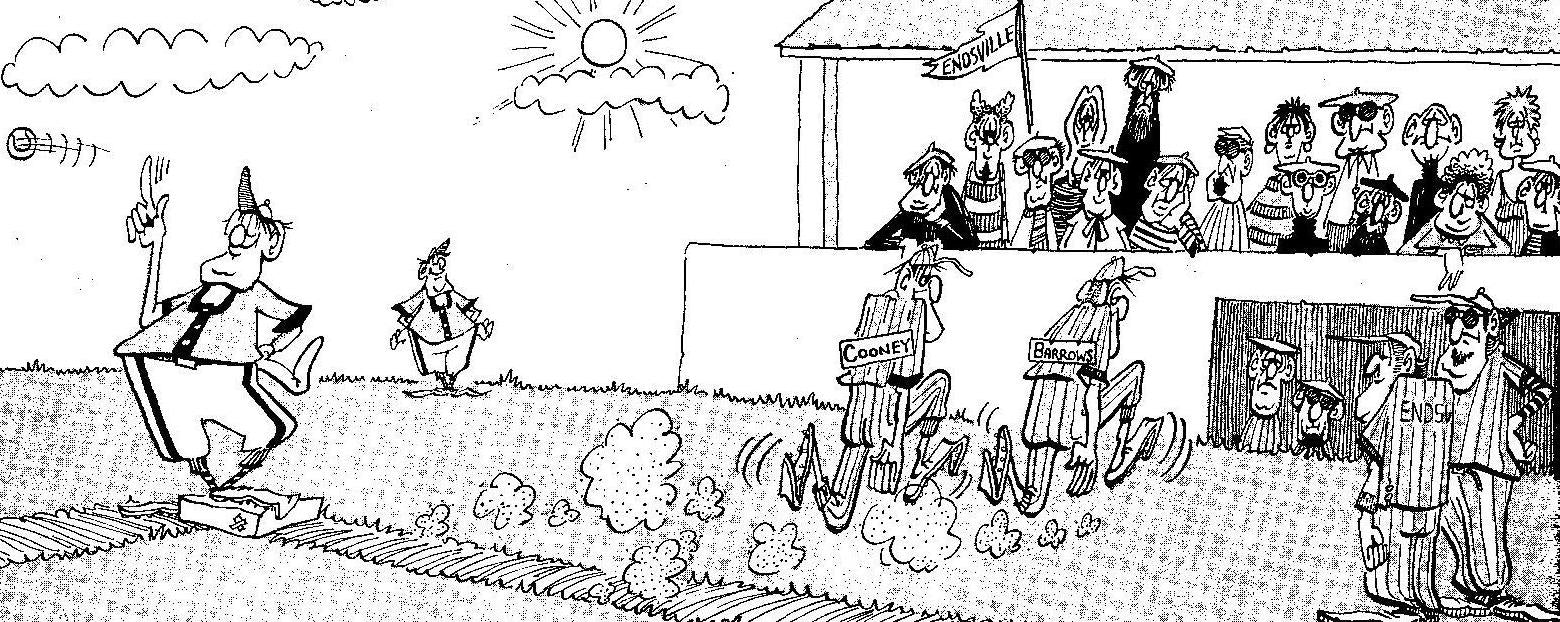

"The Admiral summoned this Captain once..." Illustration by George Bruton for "A Sea Ballad"

The Admiral summoned this Captain once,

And he gravely said to him,

"I admire your sand, but I must demand

Of you to learn to swim.

"It's all well enough to show the stuff

Of which a Captain's made,

And I much approve of the courage you've

So frequently displayed;

"But we must consider this subject from

A patriot's point of view:

Suppose you drown when the ship goes down,

Then who'll command the crew?"

The brow of the Captain bold grew stern,

And he drew a labored breath,

And he dashed his eyes if he'd jeopardize

His show for a gallant death.

"If I learn to swim," the Captain said,

"What prospect could there be

For me to win any glory in

The United States navee?"

The Admiral thought for a while, and then

He cried: "If the ship goes down,

To hell with the crew; a man like you

Mustn't lose a chance to drown."

Well, the Captain put to sea next day,

And his heart was blithesome when

He found by the lead it was over his head,

But that didn't please his men.

That night it blew a downright breeze,

The waves ran toad-stools high,

And above the shrouds a number of clouds

Were clear to the naked eye.

The Captain stood on the forward deck,

And he trembled for his craft;

He knew it must be a dangerous sea,

For he plainly felt the draft.

And the heart of the Captain bold grew faint,

And pale grew the Captain's cheek,

When he heard that cry so dreaded by

All men-of-war's men, "a leak."

Then the boatswain piped all hands on deck,

And the carpenter took command,

And in order to encourage the crew

The chaplain prayed for land.

They manned their togs, those sad sea-dogs,

And they stood by the cold roast pig,

But there wasn't enough loose matter to stuff

Up the hole it was so big.

So the carpenter came to the Captain bold,

And he mildly said to him:

"You'll surely drown when the ship goes down,

For you don't know how to swim.

We've done our best to fill that hole,

But the ship is bound to sink,

Unless you are willing to serve as as filling,

Which is little to ask, I think."

The Captain greeted this speech with joy,

And the carpenter's hand he seized,

And he tried as well as he could to tell

How deeply he'd be pleased.

The carpenter wept "How kind," he said.

"Not at all," said the Captain bold.

Then he clapped, did the "cap," himself in the gap

In the side of the good ship's hold.

He stopped that hole head first, he did,

And a bubble rose on the sea,

And when it broke that bubble it spoke,

And it said, "Hooray for me!"

And that was the end of the Captain bold,

And it's just as well that he died,

For the very next day his ship, they say,

Was wrecked by the rising tide.

Oh, list to the roar of a toothless gale,

Of a gale too weak to roar,

And hark to the swash of the waves that wash

A pleasant, sandy shore.

"PHIN" [Byline of Ernest Lawrence Thayer]

December 4, 1887

In the preamble to "A Sea Ballad," the only one introducing any of his ballads, Thayer wrote,

The author of this little ballad has long and ardently desired to immortalize in song an American naval officer of the present generation, but as the dove of peace seems to have permanently roosted on this country, and as the events of the last few years have yielded no material for sea verse of an heroic nature, the author is fain to content himself with a fictitious but not altogether improbable incident. He does not expect that his little yarn will immortalize anybody.

Here is evidence of Thayer's wry, self-deprecating humor. But his ballad also illustrates the contemporary identification of war as the primary occasion and motivation for heroism in his era. Only the generation that followed the Civil War, not the generation that fought it, could regret the "permanent roosting of the dove of peace." Thayer confessed that he had wanted to "immortalize in song" ( he was going to lampoon) "...an American naval officer of the present generation..." (of Thayer's post-Civil War generation). Viewing "A Sea Ballad" from Thayer's 1887 perspective, he was about to create, then deconstruct a paragon of military virtue.

The American navy of the 1880's did not rank high in Thayer's esteem nor in that of the public at large. Thayer characterized his hero as "very brave,/ And a trifle reckless, for / The venturesome man he sailed in an / American man-of-war." Phin's choice of the American Navy as a target for satire not only reflected the commercial success of the Gilbert and Sullivan H.M.S. Pinafore, which had debuted in London in 1878 and in New York in 1879, but also highlighted the precarious condition of the U.S. Navy itself during the 1870's and 80's. In the midst of a serious dispute with Spain in 1873 over the fate of the U.S. and British crew of the Virginius, the War Department was dismayed that it had no vessels capable of defeating a Spanish ironclad which happened to be anchored in New York harbor for repairs. By the mid-'80's, construction of the first set of modern American warships was underway, but Alfred Thayer Mahan's far-reaching influence upon the projection of American naval power around the world had yet to be felt. Mahan's The Influence of Sea Power Upon History: 1660-1783 would not be published until 1890.

More than in any of his other ballads, Ernest Thayer touched a contemporary political--and military--chord in the story of the "Captain Bold." For in the decades of the 1870's and 1880's, the American navy was struggling to reinvent itself for a new global role.

The Virginius incident in 1873 made it clear that the American navy needed to upgrade its status and global presence in order to defend national interests as well as to protect American citizens

The Virginius, a blockade runner formerly employed by the Confederate navy, had been commissioned by Cuban rebels contesting the Spanish regime in Cuba. Captured by the Spanish in 1873, the crew were declared pirates. Fifty-three men, including the American captain, were executed by Spanish authorities before the British warship Niobe arrived in Santiago to demand an end to the bloodshed. The affair triggered American anger at Spanish influence in the Americas--which ultimately would lead to the Spanish-American War--and also eerily foreshadowed the 1961 Bay of Pigs disaster, in which the U.S. became entangled in support of another ill-fated insurrection against the Cuban government.

An Indifferent Sailor--and a Brilliant Scholar

In November of 1884, American Navy captain Alfred Thayer Mahan sat in the reading room of the Phoenix Club in Lima, Peru. His ship, the Wachusett, lay at anchor in the port of Callao, about eight miles from Lima, where it had been posted to keep an eye on American and European interests during the waning months of the War of the Pacific (1879-1883) between Chile and its opponents Bolivia and Peru. Mahan's father, a professor at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., had named his son after Sylvanus Thayer (1785-1872), an early superintendent at the Academy, later known as the "Father of West Point," and who incidentally, was one of the Braintree, Massachusetts clan of Thayers from which Ernest Lawrence Thayer's family had also descended.

An indifferent sailor at best, Mahan had always preferred book-reading to sea-faring. In fact, Ernest Thayer (if he had wanted to) could not have picked a better model for a bold captain who should have stuck close to his desk and never have gone to sea, as in the lyrics of the popular "H.M.S. Pinafore"-- unauthorized productions of which had sprung up in New York in 1878.

Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914) as Captain

Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914) as Captain

From the date of his first assignment on board the steam corvette Pocahontas during the Civil War, Mahan had been involved in--or responsible for--a series of mishaps, collisions, and errors of seamanship. Commanding the sidewheel gunboat Wasp, he managed to wedge the vessel into its berth in Montevideo, becoming known as "the only commanding officer in the history of the U.S. Navy rendered hors de combat by a dry dock."[1] In his current command of the Wachusett, Thayer had collided with a bark under sail, sighted well in advance, in broad daylight and well out to sea. A subordinate officer later recalled, "Why, the Pacific Ocean wasn't big enough for us to keep out of the other fellow's way."

U.S.S. Wachusett. commanded by Captain Mahan on his South American mission

U.S.S. Wachusett. commanded by Captain Mahan on his South American mission

While Mahan waited in Peru for the end of the conflict, a letter from Commodore Stephen B Luce caught up with him. Luce was at that time instituting the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island as the location for American officers to study the relationships between strategy, diplomacy, and national power--drawing upon the lessons of history. Luce's letter to Mahan asked the latter to prepare a series of lectures on naval history and the evolution of tactics.[2]

With time on his hands, while the victorious Chilean army dismantled the bridges and railroads of Peru and appropriated the treasures of libraries and museums for new destinations, Mahan discovered an intact library at the Phoenix Club, which was maintained and frequented by expatriate Britons. He picked up Theodor Mommsen's History of Rome

...which I gave myself to reading, especially the Hannibalic episode It suddenly struck me, whether by some chance phrase of the author I do not know, how different things might have been could Hannibal have invaded Italy by sea...instead of by the long land route; or could he, after arrival, have been in free communication with Carthage by water. This clew, once laid hold of, I followed up in the particular instance."[3]

Mahan's strategic insight was derived from Rome's naval dominance

From this kernel of insight regarding Rome's dominance of the Mediterranean, Mahan cultivated his theory that the oceans were the 'great highway' upon which America could project its power-- to protect its sources of raw materials and to convey its manufactures and commodities to worldwide markets. When Mahan's book The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660 to 1783 was published in 1890, Theodore Roosevelt "devoured the book in a weekend"[4] and wrote with admiration to the author. Beginning with the example of Roman naval dominance over Carthage, Mahan had laid the intellectual foundation for the entrance of America into a new global--and imperial--era.

Count Kaneko Kenturo (1853-1942) translated The Influence of Sea Power upon History for the Japanese navy. Theodore Roosevelt introduced Kenturo to Mahan.

Count Kaneko Kenturo (1853-1942) translated The Influence of Sea Power upon History for the Japanese navy. Theodore Roosevelt introduced Kenturo to Mahan.

The imperialist party then emerging in America was not the only group devouring Mahan's insights. In fact, it was Theodore Roosevelt himself (Harvard Class of 1880) who introduced Mahan to Japanese Count Kaneko Kenturo (Harvard Class of 1878). Kenturo translated The Influence of Sea Power upon History into his own language, thereby influencing a generation of Japanese naval planners preparing to dominate the Pacific hemisphere in the twentieth century.[5] Meanwhile, by 1894, Kaiser Wilhelm was trying to learn Mahan's book by heart, and was placing it in the wardrooms of every ship in Germany's growing fleet.[6]

Ultimately, the ship of Thayer's ballad springs a leak--and the hole is so big that it cannot be filled with any "loose matter." The carpenter suggests to the Captain that the "ship is bound to sink, / Unless you are willing to serve as a filling, / Which is little to ask, I think." Whereupon "The brow of the Captain bold grew stern,/And he drew a labored breath,/And he dashed his eyes if he'd jeopardize/ His show for a gallant death." This foreshadows the fateful scenario in Casey, as the Mudville slugger contemplates the final pitch: "They saw his face grow stern and cold..."

In "The Sea Ballad" the Captain, grateful for this chance to demonstrate his gallantry and win glory, "..stopped that hole head first, he did / And a bubble rose on the sea,/ And when it broke that bubble it spoke,/ And it said, "Hooray for me!" The Captain's act was in fact Thayer's grotesque parody of the popular story of the heroic Dutch boy who put his finger in the dyke -- an apocryphal tale, not of Dutch origin, which had circulated since the 1850's but became known in America in 1865 when Mary Mapes Dodge's Hans Brinker, Or The Silver Skates was published. In 21st-century terms, Thayer's captain had personified a modern "saving hero" as opposed to a "slaying hero" of the ancient world--but the unmitigated egotism of his sacrifice reflected an ancient tradition rooted in the Homeric sagas, notably revived by Emerson in his 1841 essay "On Heroism":

There is somewhat not philosophical in heroism; there is somewhat not holy in it; it seems not to know that other souls are of one texture with it; it hath pride; it is the extreme of individual nature. Nevertheless we must profoundly revere it. There is somewhat in great actions which does not allow us to go behind them.

"A Sea Ballad" was a direct challenge to Emerson's admiration of heroic self-reliance--deflating the idealization of heroes in a post-heroic age. It also put Thayer on the road to Mudville--where, ironically, a new kind of cultural hero would soon be born.

In Thayer's final, "broken-edge" twist, the Captain's self-sacrifice comes to naught the next day, when the ship was "wrecked by the rising tide." Though Thayer could not have known it in the fall of 1887, neither tides, nor warfare, but wind and weather (compounded by errors of command and seamanship) would pose the greatest threats to the American navy of the 1880's.

On March 15-16 of 1889, an American squadron under the command of Rear Admiral L. A. Kimberly lay at anchor in the harbor at Apia, in Samoa. Kimberly's job was to keep a wary eye on a German squadron anchored in the same harbor. In this maritime stand-off--a classic instance of gunboat diplomacy--each nation had allied itself with a Samoan faction contending for local supremacy. As a peacekeeper, watching for any movement of either of the opposing naval forces, was Captain H. C. Kane in the British corvette Calliope.

In the middle of March, as the barometer dropped and signs of a pending storm grew more ominous, each squadron refused to put out to sea, though all experienced seamen knew that the best hope for surviving the storm was to leave the unsheltered harbor and ride out the storm in open water. The standoff proved a fatal one: all the American and German ships were wrecked or beached, with significant loss of life. Peacekeeping Captain Kane of the Queen's Navy distinguished himself by taking the Calliope out to sea in a narrow escape from disaster.

Storm study for the escape of HMS Calliope from the hurricane at Apia, Samoa, by William Lionel Wyllie (1851-1931). Robert Louis Stevenson, then living on Samoa as an invalid, wrote an account of the event.

Storm study for the escape of HMS Calliope from the hurricane at Apia, Samoa, by William Lionel Wyllie (1851-1931). Robert Louis Stevenson, then living on Samoa as an invalid, wrote an account of the event.

Captain Mahan, the reluctant sailor, could thank his lucky stars that by this time he had been safely reassigned to the Naval War College in Newport. The Navy split his time between sea and classroom duty, but by the time Mahan took charge of his last command, the modern steel cruiser Chicago in 1893, he was probably a better candidate for retirement. When in May, 1893 the Chicago banged up against the training ship Bancroft in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Mahan's record unique record remained intact: he had "grounded, collided, or otherwise embarrassed every ship (save the Iroquois) he ever commanded."[2]

Officers of the protected cruiser Chicago, circa 1893-1895. Capt. Alfred T. Mahan is sitting at left . (Gift of Capt. Bruce Canaga, now in the collections of U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command)

Though in mid-1893 Mahan was confined to sick bay and then put on leave, his ill fortune had already attached itself to the Chicago. The captain of the British tanker Azov crashed his ship into the Chicago as it was anchored in the Scheldt Estuary in the Netherlands. Mahan’s crew — by this time accustomed to emergency procedures — prevented major damage to their ship by quickly repairing the damage to the hull. Even if he had been on board, it is unlikely that Mahan would have volunteered to plug the breach himself. In 1894, he was finally able to retire--fortunately with a reputation well-established by scholarship rather than dependent upon his shaky seamanship. Not only had he written 137 scholarly articles and 20 books, but his Influence of Sea Power had forever altered the strategic thinking of 20th century navies -- and had buoyed American aspirations to dominate oceans around the globe.[7]

The U.S.S. Chicago was built in the first round of "steel navy" additions to the U.S. fleet, designed to bring the U. S. Navy into the 20th century

The U.S.S. Chicago was built in the first round of "steel navy" additions to the U.S. fleet, designed to bring the U. S. Navy into the 20th century

As for Thayer's "Sea Ballad," inspired by the famed W. S. Gilbert, this wry satire on the shortcomings of the U.S. Navy achieved no immortality either for itself or for its author, just as Thayer had predicted. But the dramatic circumstance of the poem-- a protagonist aspiring to heroism against overwhelming odds in the presence of spectators entirely dependent on the outcome--would soon find new expression in a place called "Mudville," in a Ballad of the Republic which would elevate the protagonist of "Casey at the Bat" to the pantheon of American folk heroes.

[1] U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph of a portrait in oils by an unidentified artist, from the Navy Art Collection, Washington, DC [2] Dr. Larrie D. Ferreiro has brilliantly traced the origin of Mahan's naval theories to his days in the library in Lima during the fall of 1884. See "Mahan and the "English Club" of Lima, Peru: The Genesis of The Influence of Sea Power upon History," in The Journal of Military History 72 (July 2008), pp 901-906. [3] Alfred Thayer Mahan, From Sail to Steam: Recollections of Naval Life (New York: Harper Brothers Press, 1907; repr. New York, Da Capo Press, 1968), p. 277, cited in Ferreiro, ibid. [4] See Scott Miller, The President and the Assassin (New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2013), p. 53 [5] See James A. Smith, "The Influence of Alfred Thayer Mahan upon the Imperial Japanese Navy," submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Military History, for Professor Bernd Horn (Military Thought and Theory), Norwich University, November 10, 2013. Smith concludes that Mahan's influence on the Imperial Japanese Navy "proved to be a frustrating, indeed, fatal, infatuation...The influence of Mahan on Japanese naval thinking was profound, but it was not salutary."

[6] Evan Thomas, The War Lovers: Roosevelt, Lodge, Hearst, and the Rush to Empire, 1898. (New York: Little Brown & Company, 2010), p.71.

[7] Donald Lankiewicz (American History Magazine), "Alfred Thayer Mahan and his vain quest to keep ships straight," Navy Times (navytimes.com), October 14, 2019.

#BalladoftheRepublic #CaseyattheBat

Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914) as Captain

Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914) as Captain U.S.S. Wachusett. commanded by Captain Mahan on his South American mission

U.S.S. Wachusett. commanded by Captain Mahan on his South American mission Count Kaneko Kenturo (1853-1942) translated The Influence of Sea Power upon History for the Japanese navy. Theodore Roosevelt introduced Kenturo to Mahan.

Count Kaneko Kenturo (1853-1942) translated The Influence of Sea Power upon History for the Japanese navy. Theodore Roosevelt introduced Kenturo to Mahan. Storm study for the escape of HMS Calliope from the hurricane at Apia, Samoa, by William Lionel Wyllie (1851-1931). Robert Louis Stevenson, then living on Samoa as an invalid, wrote an account of the event.

Storm study for the escape of HMS Calliope from the hurricane at Apia, Samoa, by William Lionel Wyllie (1851-1931). Robert Louis Stevenson, then living on Samoa as an invalid, wrote an account of the event.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.