Casey and the Golden West

The notion of Ernest Thayer's "Casey at the Bat" as a literary emblem of America's Golden West occurred to me as I read MLB's official historian John Thorn's recent post, "The Game of the Golden West." Thorn's essay is a meditation on early baseball as it came to be played and celebrated in the West, and how the Western version of the game eventually rescued baseball in the East. As Thorn writes,

When Horace Greeley said, “Go West, young man,” he supplied the watchword of Manifest Destiny, the doctrine of America’s prophetic role among the world’s nations, in which its ideals and territory would o’erspan the continent. “Long ere the second centennial arrives,” Walt Whitman declared in 1876, “there will be some forty to fifty great States, among them Canada and Cuba.”

This prediction was indeed borne out, not in the USA’s constituent parts, but in its professional baseball leagues. To go west, following the sun toward milk and honey and riches, was to return to an unspoiled Eden, fulfilling the destiny of the individual and the nation.

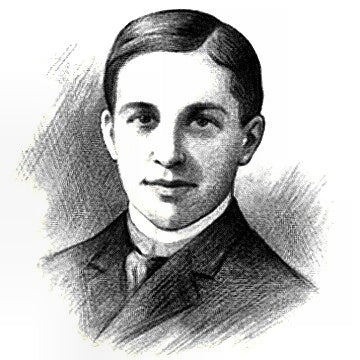

Ernest "Phinney" Thayer (1863-1940) as a student

Ernest Thayer, the quintessential Easterner--raised in Worcester, Massachusetts; son of a woolens manufacturer, educated at Harvard--seems an unlikely avatar for baseball's westward migration. But in fact the legend of Casey is deeply rooted in the young Thayer's infatuation with the raw, inchoate vitality of California--where Thayer and his pals from the Harvard Class of '85 joined their former classmate William Randolph Hearst in his campaign to re-make the San Francisco Examiner.

Thayer took on several assignments for the Examiner. In 1887, he became a featured columnist in the Sunday edition, writing a series of ballads from September through December. As a reporter, he would have been one of publisher Hearst's "detectives" tasked with solving crimes, finding lost relatives, and investigating the malfeasance of local officials (see " The Strange Romance of a Bold Detective" https://caseyatthe.blog/blogs/caseyatthe-blog/was-thayers-story-that-of-the-bold-detective.

But more importantly to the story of "Casey," Thayer also became the Examiner's baseball reporter. Though in later life, he would downplay his youthful interest in baseball, there is no doubt that Ernest was well-equipped by experience and temperament for sports-writing. Not only during his college years did he attend the games of the famed Harvard Nine, captained by his childhood pal Sam Winslow, but he also observed and reported on games between the California teams of his era. In addition, Thayer's narrative flair and his evocative writing style, honed on his high school newspaper (the Monohippic Gazette) and sharpened as editor of the Lampoon were well-suited to the nine-inning dramas of local baseball.

Two San Francisco teams, the Haverlys and the Pioneers, played at the new ballpark at Haight and Ashman on Sunday, October 9, 1887. It is likely that Thayer attended this game.

It is also likely that Thayer took the train (or the steamboat) to Stockton to see games played in the ballpark at Banner Island, where today the Stockton Ports play in a modern venue on the site of the original park. Due to frequent inundations of the San Joaquin River, Stockton in Thayer's day was often referred to as "Mudville." And players in Stockton during the 1887 season included an outfielder named Cooney and a pitcher and shortstop named Flynn--both names featured as players on the Mudville Nine of "Casey at the Bat." Stockton's geography even seems to mirror that of Mudville, where the "lusty yell" of the crowd as Casey approached the plate "rumbled through the valley, it rattled in the dell;/ It knocked upon the mountain and recoiled upon the flat..." The valley, dell, and flat compare to the broad delta of the San Joaquin River; as likewise Mudville's "mountain" evokes the nearby Mount Diablo.

Ralph Yardley illustrations of the 1888-89 Stockton ball team and their home park at Banner Island on the San Joaquin River

Holliston, Massachusetts--like Stockton, California--has a solid claim to the inspiration for Thayer's "Mudville," with an historic neighborhood populated in the 19th century by Irish immigrants. Thayer's mother's family, the Darlings, owned a nearby mill and Thayer's family kept a summer home not far away in Mendon. Caseyatthe.blog will pose a new question; "When was Mudville?"

The Buffalo Hunt

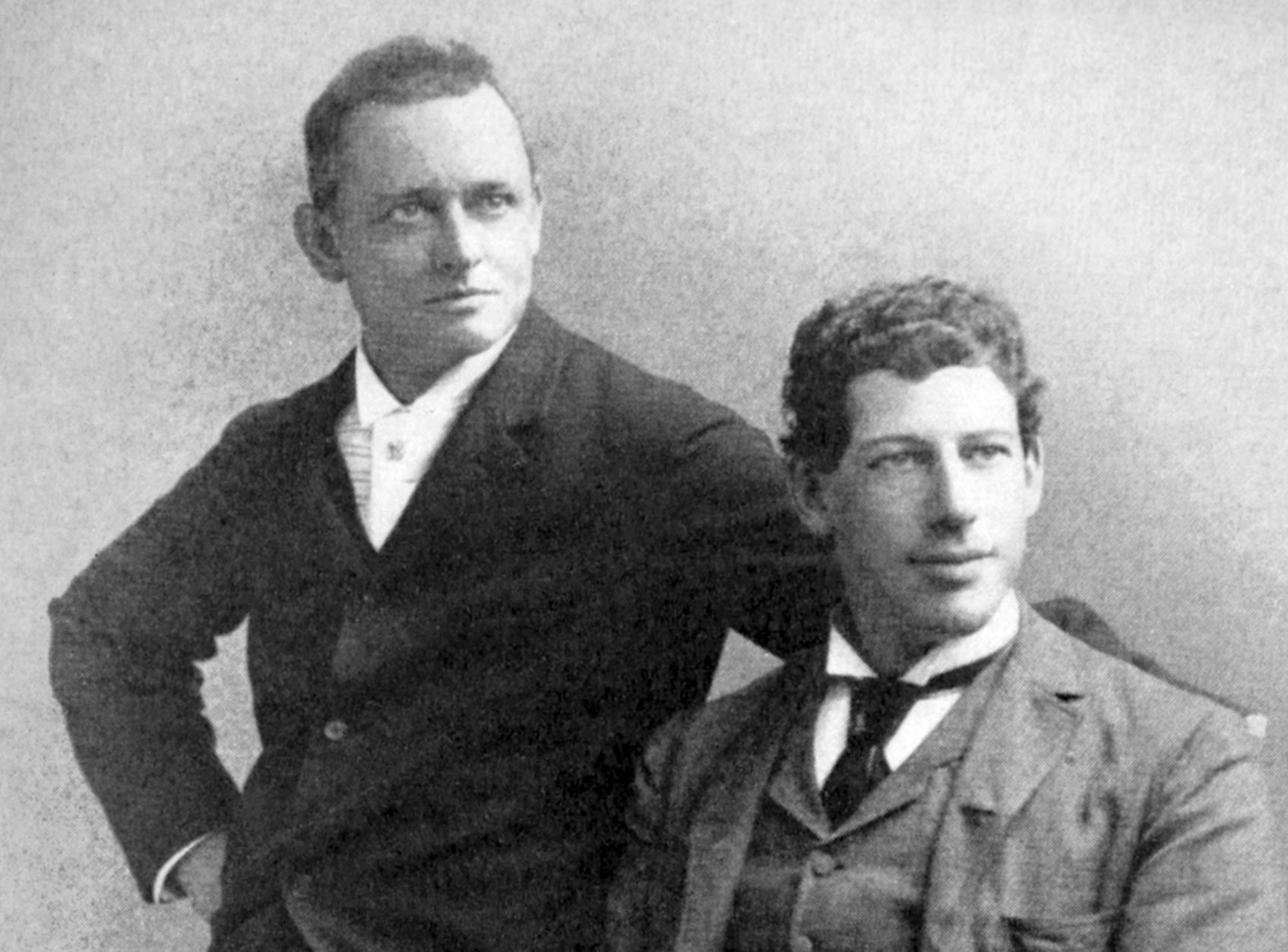

In his authoritative role as America's Simile Man--the author of the first modern dictionary of similes published in English, Frank Wilstach was well-positioned to confer immortality upon his departed friend and fellow newspaperman Will Valentine. Journalist, theatrical promoter and literary antiquarian Wilstach had since late 1904 been promoting a story published in newspapers nationwide. His account told of a "certain Sunday afternoon" in the mid-1880's (Wilstach was never very clear on the exact date), as two young journalists on the staff of the Sioux City Tribune were whiling away their time. Young Frank Wilstach, himself the son of a literary family from Lafayette, Indiana, told several versions of the following story:

Will Valentine, a young Irishman, came up from the Kansas City Star to the Sioux City (Iowa) Tribune in 1885 to be city editor. He was constantly writing verse. On the back page of the Tribune I was at that time conducting a column which, shamefacedly I may say, was supposed to be like Eugene Field's "Sharps and Flats" in the Chicago Record. It was bad, but Valentine every once in a while would hand me a bit of verse which I would run, he signing it "February 14" being St. Valentine's day, as 'twere.

Valentine and I were roommates. My brother Walter sent me a set of Macaulay's works and one Sunday evening, reading "Horatius at the Bridge," I said to Valentine that here was a good opportunity to parody "Horatius" by a poem about a Mick at the Bat. We were then baseball crazy. Valentine read the Macaulay poem and went ahead and wrote a piece he called "Casey at the Bat."

It is rather curious (Wilstach went on) that all the claimants for this poem have been seemingly unaware that "Casey at the Bat" is a parody on "Horatius at the Bridge," with the same meter and the end of each stanza very nearly the same.

I left Sioux City in 1887, wrote Wilstach, and never heard of Valentine or thought anything of his poem until one night I met him on lower Broadway in 1898. I was then press agent at the Broadway Theatre and Valentine was employed on the New York World. .....

We know that whether or not Wilstach was working for the Broadway Theatre at this time, that he could not have met Will Valentine on Broadway in 1898. Valentine's body had been in the grave since July 1897. He had died of a virulent middle ear infection while managing the Octagon Hotel on Oyster Bay.

Frank Wilstach's motives for pushing the alternative authorship of "Casey" are murky. By the time Frank began promoting his story of the Sunday afternoon discovery of Macaulay's ballads of ancient Rome, Will Valentine had already been dead for seven years. We do know, however, that from 1896 until perhaps mid-1900, Wilstach had served as DeWolf Hopper's press agent and promoter--a close relationship that appeared to end rather abruptly. The true story of Frank's attempt to debunk Thayer's authorship probably had more to do with backstage grievances and intrigue within the theater world, particularly as Hopper's crowd-pleasing recitations of "Casey at the Bat" had become popular from coast to coast.

Yet Wilstach insisted well into the 1920's that his pal Valentine had been the true author of "Casey at the Bat." When Wilstach published the first edition of his Dictionary of Similes in 1916, he had a unique opportunity to bolster the evidence on behalf of Will Valentine's authorship. The poem "Casey at the Bat," in addition to introducing an unforgettable hero to a baseball-crazed nation, had also displayed within the four lines of its ninth stanza a particularly memorable simile, standing out within the otherwise sparely crafted narrative of the poem as a true humdinger of its kind.

In the ballad, Casey has just ended the eighth stanza with a disdainful glance at the first pitch, jesting in an offhanded way, "That ain't my style." Unimpressed, the umpire declares, "Strike one!"

Opening the ninth stanza, the crowd's wrath is epic in scope:

From the benches, black with people, there went up a muffled roar,

Like the beating of the storm waves on a stern and distant shore.

Like the beating of the storm waves on a stern and distant shore......

Keith Bendis illustration from Casey at the Bat (New York: Workman Publishing, 1987). Bendis is the only one of "Casey's" many illustrators to imagine this memorable line.

Wilstach's A Dictionary of Similes in fact contains some thirty-seven entries demonstrating similes both for "roar" as a noun (seven entries) and thirty more for "roar" as a verb or verb form. These include attributions to Kipling ("...like the roar of a mortar battery"); Longfellow ("...like a flame that is fanned"); Shelley ("...as of an ocean foaming"); Wordsworth ("...like lions for their prey"); and Macaulay, from the "Battle of Lake Regillus," in his Lays of Ancient Rome: "...like the roar of a burning forest, when a strong north wind blows."

A simple attribution of "Casey's" notable simile, under the heading "Roar," could have credited his friend and colleague Will Valentine. naming the latter as the ballad's rightful author and (as Frank supposed), would have helped Wilstach validate his longstanding claim on Valentine's behalf.

By the time the second edition of Dictionary of Similes had been published in 1924, "Casey" had successfully eluded Wilstach's decades-long attempt to capture its authorship for Will Valentine. But Wilstach unknowingly provided another clue to "Casey's" literary provenance. He inserted this simile from a poem by Bayard Taylor, under the heading "Roar":

Like the din of wintry breakers on a sounding wall of shore.

George Catlin (1796-1872), The Buffalo Hunt (ca 1832)

Taylor's full poem, "The Bison Track," is an account of a buffalo hunt on the Great Plains, and the full stanza (recounting the stampede of a mighty buffalo herd) reads

See! a dusky line approaches: hark, the onward-surging roar ,

Like the din of wintry breakers on a sounding wall of shore!

Bayard Taylor (1825-1878) was a well-known American poet, diplomat, critic, travel writer, and professor of German literature at Cornell. Not only does Taylor's poem display a meter echoing that of "Horatius" and "Casey," but Thayer's simile parallels Taylor's so closely that Thayer must have deliberately incorporated it into the ninth stanza of "Casey". But "the beating of the storm waves / on a stern and distant shore" in "Casey" is a distinct improvement on the original Taylor line "The din of wintry breakers on a sounding wall of shore." The image of "A stern and distant shore," for example, is far more evocative than Taylor's " sounding wall of shore." Thayer summoned up an austere landscape of ancient times in the same way as did Macaulay in the Lays of Ancient Rome, as for example from Stanza XXXVII of "Horatius":

"...From that grey crag where, girt with towers,

The fortress of Nequinium lowers / O'er the pale waves of Nar."

Here as elsewhere, Thayer displayed his ability to transform and elevate the literary elements from which "Casey" is crafted. And as this blog has demonstrated elsewhere, Thayer did not hesitate to reference the classics--though his allusions were tantalizingly subtle. Besides the template of Macaulay's "Horatius," Thayer employed not only the simile provided by Taylor but also lines from Alexander Pope's 1734 "Essay on Man" ("hope that springs eternal in the human breast"). And, I will argue, Thayer borrowed the trope of an ode to Springtime in "Casey's" final stanza from Shakespeare's evocative coda to "Love's Labours Lost." But that's a topic for another blogpost.

Author, poet, and diplomat Bayard Taylor 1825 - 1878

Author, poet, and diplomat Bayard Taylor 1825 - 1878

The Tyro Bank Robbery: Kloehr of Coffeeville Strikes Out

The Wild West persisted well into the twentieth century in Kansas towns like Dodge City and Abilene--the latter renowned in cowboy legend as the headland of the Chisholm Trail. On March 13, 1908, a pair of desperados with roots in Cherokee Indian territory (located in what is now northeastern Oklahoma) crossed the border into southeastern Kansas. Their target was the recently-incorporated town of Tyro, its population (then approaching six hundred) capable of sustaining a branch of the State Bank. The gunmen, armed with two Winchesters and five hundred rounds of ammunition, made a forcible but bloodless withdrawal of $2,500 from the Tyro branch and headed south toward Osage country.

Main Street of Tyro, Kansas ca 1908

The Emporia (Kansas) Gazette of March 18, 1908, under the headline "Casey at the Bat," satirized the pursuit of the "gang" (the Gazette was then unaware of the number of robbers). The gist of the Gazette's editorial was that following the robbery a posse was hastily assembled by the Tyro townsmen to apprehend the outlaws. We know from other accounts that lawmen and civilians numbering about twenty by sundown were surprised by a hail of bullets from the edge of a woodland. The pursuit was stymied. As darkness fell, reinforcements from Tyro began firing on a civilian reconnaissance party from the Oklahoma town of Wann. Meanwhile, the bank robbers were lengthening the distance between themselves and the representatives of justice.

Condon & Company Bank, target of the Dalton Gang in Coffeeville, Kansas in 1892. This was the scene of a violent shootout following a failed attempt by the infamous Dalton gang to rob the bank on October 5, 1892. Four of the gang were killed, as were four citizens of Coffeeville, while Emmett Dalton, surviving twenty-three gunshot wounds, was imprisoned for fourteen years before being pardoned.

Before the local militias could inflict fatalities on each other, or on innocent civilians, someone had the idea to call upon more experienced leadership. Fortunately--or unfortunately-- the Kansas borderlands had some history to draw upon. Only twelve miles from Tyro lay the town of Coffeyville, the scene of one of the bloodiest shootouts in Western lore. On October 5, 1892, the Dalton brothers, cousins of the infamous Younger gang, had planned to pull off the daring feat of robbing two banks simultaneously. While $20,000 was easily extracted from the First National Bank, a teller at the Condon & Co. Bank across the street stalled the robbers with the falsehood that a "time lock" made it impossible to open the vault. The delay allowed local citizens to arm themselves, and as the gang rushed to their horses, the locals opened fire. Among the civilian defenders that day was a man named John Kloehr, whose later version of events claimed that he had single-handedly fired the shots which had killed all but Emmett Dalton, the lone survivor of the gang.

Calling on the captaincy of John J. Kloehr, the would-be heroes of Tyro regrouped to plan a more systematic pursuit. Several of the original volunteers skedaddled for home when the time came for the actual business of riding, chasing, and shooting. Eventually some of the posse were waylaid and relieved of their horses and weapons by the "gang" they had set out to capture. The Gazette drew its humor from the distinction between the aspirations of the would-be heroes and their ignominious "strike-out":

When the dire news of the robbery came to the startled people of Southern Kansas, men of martial instincts at once called for their guns and called for their steeds, and called for their snickersees, and there was much saddling of horses and breathing of gory threats, and mixing of war medicine. Shame on the false Etruscan who lingers at his home at such a time!

...The horses of some went lame, and a few suddenly remembered that they had important engagements in town, and the chase languished, so that it seemed the robbers would reach their fastnesses unscathed and untrammeled.

It was then the people clamored for Kloehr, of Coffeyville. He it was who shot down bank robbers in their tracks and performed other feats which have been immortalized in the Street & Smith publications. "Hark, the cry is Astur, and lo, the ranks divide, and the great lord of Luna comes with his stately stride."

John J. Kloehr, participant in the Coffeeville shootout that put an end to the Dalton Gang. In a New York Sun article on April 8, 1906, Kloehr told a version of the story in which he had single-handedly killed four of the gang and disabled Emmett Dalton as the survivors rushed for their horses.

Smith & Street (1855-1959) were the publishers of pulp fiction and "dime novels" as well as {later} comic books such as "The Shadow."

The Emporia Gazette continued:

Kloehr, of Coffeyville, has come to the rescue. "And on his ample shoulders clangs loud the four-fold shield, and in his hand he holds the brand that none but he can wield."

Lawman Kloehr did not "scatter the brigands," nor did he bring them to justice--to the amusement of the Emporia Gazette and its readers. The editor had defined the self-promoting John Kloehr as a "Casey"-like character whose reputation at the plate far exceeded his actual performance--and he bracketed Kloehr's description with the classical stanzas from Macaulay's "Horatius" to make the point with devastating clarity.

Notably the Gazette portrayed the Tuscan champion Astur, rather than the Roman hero Horatius, as the protagonist from whom the role of "Casey" was drawn. We know the author of this derisive commentary--his name appears on the masthead right above the editorial as "W. A. White." He was William Allen White (1868-1944), famed newspaper editor, author, leader of the Progressive movement, and friend of Theodore Roosevelt. White's autobiography, published posthumously in 1946, won the 1947 Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography. Born in Emporia, known in his lifetime as a spokesman for middle America, the "Sage of Emporia," though no Harvard man, was one of the journalistic luminaries of his age. He studied at the College of Emporia and the University of Kansas, and cut his eye teeth as a writer at the Kansas City Star, where he began work in 1892. Educated in the nineteenth century and about to make his mark in the twentieth, William Allen White was one reader who "got" Thayer's humor, seeing through the transparency of "Casey's" baseball setting to the framework set by Macaulay, borrowed from Livy and the legends of ancient Rome.

William Allen White (1868-1944) -- newspaperman, author, Progressive politician, and friend of Theodore Roosevelt, known as the "spokeman for Middle America" (Unknown photographer, Library of Congress, Bain Collection)

William Allen White, having his fun with the amateur lawmen of southern Kansas, might not have bestrewn his witticisms so freely had he known that the robber escaping deeper into the former Indian territory, was none other than the notorious Henry Starr, whose outlaw career would span three decades. Self-educated, articulate, abstemious, charming when he chose to be, the part-Cherokee Starr had tried and failed several times to "go straight." His conviction for a murder committed in the course of escape from the robbery of the People's Bank of Bentonville, Arkansas (Starr claimed that his pursuer was killed in a classic duel, fair and square) had been overturned by the Supreme Court of the United States. Re-tried and sentenced to fifteen years for robbery and manslaughter, Henry was transported to the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus in 1898, where he pursued studies in ancient history, criminology, and the science of firearms. Based on Starr's role as model prisoner, the warden in 1901 had recommended (and the Cherokee tribal government had endorsed) a presidential pardon. Impressed with Starr's biography (Henry had disarmed a fellow prisoner during a prison riot in Fort Smith, where he had been held following the Bentonville robbery), President Roosevelt duly issued the pardon and Henry was released in January 1903. In 1904 Henry named his newly-born son "Theodore Roosevelt Starr."

Henry Starr (1873-1921), born in Indian Territory to part-Cherokee parents, pursued an outlaw career well into the 20th century. He claimed to have robbed more banks than the James / Younger and Doolin / Dalton gangs together. Paroled in 1919 for his part in a daring bank robbery in Stroud, Oklahoma, Henry "went straight" long enough to star in a silent film dramatizing the Stroud robbery (Poster by Pan American - HA, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=46430668)

But not even the combined mercies of the U. S. Supreme Court and President Theodore Roosevelt could dissuade Starr from returning to his old ways in 1908. The Tyro bank job was only the next in Starr's long tally of crimes; nor would it be his last.

William Allen White was probably unaware that his friend Theodore Roosevelt was at least partly responsible for unleashing Henry Starr's criminal appetites upon the citizens of southeastern Kansas. But White's witticism nonetheless provides a vital clue to the biography of "Casey at the Bat," demonstrating that Thayer's contemporaries had clearly fathomed the connection between "Casey" and "Horatius."

Thayer's creative powers now may be fully recognized, just as they were in 1908, when placed in the context understood by readers of Macaulay's poem. What's the evidence of this? Because of the way in which "Casey's" epic is told--from a reversed, mirror-image viewpoint of Macaulay's tale of the battle at the Sublician Bridge. As the editor of the Emporia Gazette realized, the climactic moment of hand-to-hand combat in Macaulay's poem is personified by the Tuscan champion Astur advancing to the bridgehead, his scornful look mimicked by Casey as he silenced the Mudville protesters:

He smiled on those bold Romans

A smile serene and high;

He eyed the flinching Tuscans,

And scorn was in his eye.

The heroic Tuscan Astur-- the third champion to engage Horatius at the bridge-- struck a memorable blow which went amiss, with fatal results

In the long run, based on its classical template, timeless dramatic formula, and universal themes, the "Casey" saga would firmly establishing its appeal within American culture. And as baseball competition spread around the world in the 20th and 21st centuries, that appeal is poised to cross not only national but also cultural boundaries (see "Queci al Bate" article in Caseyatthe.blog ). But it's worth remembering that within its own time and place, Thayer's "Casey at the Bat" can claim not only a Western origin, and the incorporation of a notable Western simile from "The Bison Track," but also a contemporary Wild-West interpretation of its literary origins by a famed Kansas journalist. In the borderlands of the untamed West, brigands still roamed in the early years of the 20th century--and heroes could still rise up (or fall, as did John Kloehr), even if their exploits would become dramatized to the American public chiefly in the pages of dime novels or on the flickering screens of movie houses.

Thayer certainly lived long enough to appreciate that soon after the dawning of the 20th century, "reel heroes" would replace the real heroes of the age--or of ages past. The ironies suffered by his post-heroic generation had in fact inspired Thayer's 1885 Class Day oration to the graduates in Harvard Yard: "There is no place in Cambridge for the young man of heroic intentions."

The Majestic Theatre, Detroit, ca 1910

@stocktonports @mlblondonseries @mlbuk @MLBUKCommunity @baseball_ref @thorn_john @SABR @baseballhof @BaseballBrit #CaseyattheBat #BalladoftheRepublic @OnlyAGameNPR @SBNation @MartinKessler91 @klgiven @PawSox @PolarPark2021 @SBHistoryMuseum @worcestermag @tgsports @PulpEphemera @baseballminutia @BBHistoryDaily @nut_history @RedSox @DickFlavin @SportLiterate @NYY_Report @InthePastLane @PaineProfitt @ClaytonTrutor @HofDigital @MattBaseballGB @archivesfdn @sfchronicle @radio_worcester @Worcester_PL @BaseballAmerica @Dingerball1 @TweetWorcester

Author, poet, and diplomat Bayard Taylor 1825 - 1878

Author, poet, and diplomat Bayard Taylor 1825 - 1878

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.