Misappropriation of the Classics: "Horatius" Reclaimed

Since its inception in 2018, Caseyatthe.blog has tried --and mostly succeeded--to steer clear of the reefs and shoals of political discourse. (One notable exception--"Mueller at the Bar" on October 8, 2019). But when Steve Bannon and his co-host Jack Maxey exhorted their "War Room: Pandemic" listeners to fight and die for a second Trump term--misusing Thomas Macaulay's epic "Horatius" to make the point--Caseyatthe.blog must register an objection in the strongest possible terms.

Thanks to Madeline Peltz at Media Matters for America for checking the facts and exposing this pernicious misappropriation of an ancient legend. Media Matters for America describes itself as a web-based, not-for-profit, 501 (c)(3) progressive research and information center dedicated to comprehensively monitoring, analyzing, and correcting conservative misinformation in the U.S. media. Check out Ms Peltz's article "Steve Bannon suggests that Americans should fight and die for a second Trump term."

The spreading of misinformation of this sort is not just a literary or academic foray. Because it has become clear in the last few days that Steve Bannon has been the Svengali whispering from the shadows that traditional norms and practices of American democracy can be subverted, that legally-cast votes in America's recent election can be ignored or perverted by state legislatures, and that a handful of legislators in swing states can replace American democracy with a form of autocracy--based on an atavistic principle of minority rule.

Steve Bannon--to refresh memories sated with other news since August 2020-- is the former Trump campaign CEO, Breitbart News chairman, and former White House strategist. In August he was indicted by New York prosecutors for fraud and conspiracy to commit money laundering--in connection with the "We Build the Wall" fundraising campaign. You may also recall that Bannon was recently sanctioned by social media platforms for advocating the beheadings of Dr. Anthony Fauci and of FBI Director Christopher Wray.

In response, to start with, are the facts about "Horatius"--or as many of the facts as we can stipulate from accounts of a battle that took place over 2,500 years ago.

Why the Battle?

In the late 6th century BCE, the city-state of Rome was part of the Etruscan confederation of city-states dominated by the city of Clusium. Rome itself was governed by a king, the seventh and last of his dynasty --Lucius Tarquinius Superbus--a name translated as "Tarquin the Proud," but which could also be understood as "Tarquin the Arrogant." Tarquin came to power by the brutal assassination of his predecessor--his father in law--and involved Rome in a series of wars against neighboring colonies. Even so, Tarquin might have kept his throne, had not his son Sextus raped a senator's wife. The virtuous Lucretia summoned her husband and his kinsmen and disclosed the outrage perpetrated by the crown prince. While the men dithered over a response, Lucretia seized a knife and challenged the nobles, according to one version of the story: "if you are men, and if you care for your wives and children, exact vengeance on my behalf and free your selves and show the tyrants what sort of woman they outraged, and what sort of men were her menfolk!" With that, she plunged the knife into her own heart.

Tarquinius Superbus -- by Lieven Mehus (1630-1691)

Displaying the bloody weapon, Brutus--ancestor of the more well-known Marcus Junius Brutus, the assassin of Julius Caesar-- recruited revolutionaries who swore they would expel Tarquinius, his sons, and his wife from Rome, and would never more be ruled by a king.

The Rape of Lucretia, by Giulio Cesare Procaccini (1570-1625 )

The Tarquins fled to Lars Porsena, ruler of the Etruscan city of Clusium and overlord of the Etruscan confederation. In one version of these events, Tarquinius Superbus begged for Porsena's help to crush the rebellion and reinstate his dynasty on the Roman throne. Porsena, in another version, saw the expulsion of the Tarquins as a pretext to establish his own direct rule of Rome. But accounts agree that in 509 BC the Tuscan allies, summoned by their overlord, marched upon the Roman defenses. Overwhelming the Roman outpost upon the Janiculum hill, west of the city, the Tuscan allies found themselves at the final barrier: the River Tiber, spanned by a single wooden bridge.

J. R. Weguelin (1849-1927), Lars Porsena before the Gates of Rome

Facing Fearful Odds

The Roman rebels had challenged not only the secular power of Etruscan authority but also the manifestation of nature's divine power which that authority claimed to embody. No wonder the Roman Senators in Macaulay's version of the tale contemplated the arrival of Lars Porsena and his combined armies at the gates of Rome with sinking hearts:

.. In all the Senate

There was no heart so bold

But sore it ached, and fast it beat,

When that ill news was told.

The odds seemed stacked in Porsena's favor. In "Horatius," thirty chosen prophets--the pundits and pollsters of their day-- had foretold the success of his military expedition:

‘Go forth, go forth, Lars Porsena;

Go forth, beloved of Heaven;

Go, and return in glory

To Clusium’s royal dome;

And hang round Nurscia’s altars

The golden shields of Rome.’

Francois-Joseph Navez (1787-1869), "The Oath of Brutus." In the legend, following the death of Lucretia and the expulsion of the Tarquins, Lucius Junius Brutus assembled the Roman people and had them swear an oath never to allow a man to be king in Rome. In the painting, Brutus holds the knife with which Lucretia took her own life--affirming her loyalty to her husband and challenging her kinsmen to avenge her defilement and death.

Francois-Joseph Navez (1787-1869), "The Oath of Brutus." In the legend, following the death of Lucretia and the expulsion of the Tarquins, Lucius Junius Brutus assembled the Roman people and had them swear an oath never to allow a man to be king in Rome. In the painting, Brutus holds the knife with which Lucretia took her own life--affirming her loyalty to her husband and challenging her kinsmen to avenge her defilement and death.

On the western approach to the bridge the half-blind captain of the guard, Horatius "Cocles" (One-Eye) stood to defy the mighty army commanded by Lars Porsena. Flanked by two sturdy wingmen, Horatius confronted the Etruscans on the apron of the narrow bridge while his countrymen chopped away at the wooden pilings and abutments behind him. In three vicious rounds of single combat (in Thomas Macaulay's versification of the story), Horatius and his companions held back the Etruscan vanguard long enough for the Romans to collapse the bridge into the Tiber, thus preserving their infant Republic.

"Horacio en el puente," by Severino Baraldi (b. 1930)

Madeline Peltz, writing for Media Matters, notes "For years, Bannon has cloaked his extremist positions with obscure and pretentious references." "Horatius" may seem obscure to 21st century readers, but the authors of the U.S. Constitution were quite familiar with the origins of the Roman Republic, which in many ways they attempted to model as they constructed the framework of our own American government and electoral system. Contrary to attempts in recent years to draw a line separating the establishment of the American Republic and the expansion of voting rights from the Civil War onward, the idea of universal suffrage has its roots in the Roman Republic. Within a few years of achieving independence from Etruria, the plebeians of Rome by 494 BCE had asserted their right to participate in the making of laws through political and electoral processes. From this time forward, the plebeians elected tribunes to defend their interests--representatives who were immune from arbitrary arrest and who could veto legislation. Likewise, the story of Lucretia and her tragic role in the uprising against tyranny continued as a theme in art, literature, and music up through the 20th century.

In the mid-19th century, the legend of "Horatius at the Bridge" (as it became known in America) was revived by English parliamentarian and historian Thomas Macaulay. It was Macaulay's conceit that his collection Lays of Ancient Rome was a reconstruction of the ancient songs and folklore from which Livy and later Roman historians drew their narratives of Roman glory. Macaulay's verses were committed to memory by generations of British and American schoolchildren.

"Horatius": The Legend

English critic Matthew Arnold (1822-1888) found in the Lays of Ancient Rome the touchstone of the "grandly bad" in poetry. But in the 19th-century context, this assessment is too harsh: Macaulay's histories, essays, and poetry were adored in America by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, William Dean Howells, and Louisa May Alcott, among thousands of others. In 1864, Ohio Colonel Dan McCook led his brigade into battle against Confederate entrenchments at Kennesaw Mountain with an exhortation of lines from "Horatius." British soldiers in the first World War often recalled the defense of the Roman bridge in describing their own experience of battle; Winston Churchill relied upon the example of Horatius to inspire his countrymen during the War against Hitler; while generations of British schoolboys kept alive the Lays of Ancient Rome well into the 20th century.

"England vs Wales," from The Illustrated London News, January 9, 1892

Among these young scholars was the teen-aged J.R. R. Tolkien, who with his pals at King Edward's School took their rugby seriously. Tolkien's first attempt at epic poetry, "The Battle of the Eastern Field" between the "Reds" and the "Greens", written for the school's Chronicle, parodied Macaulay's form and style from "The Battle of Lake Regillus," the second of Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome .

Tolkien, of course, was a prolific borrower from the lore and languages of the past. So consider Gandalf's defiant stand at the Bridge of Khazad-dum within the ancient dwarf-realm of Moria, as the nine members of the Fellowship of the Ring make their escape from an onslaught of orcs, trolls, and ultimately, the feared demon of the Underworld--the fiery Balrog. As the fleeing Fellowship approach the fearful chasm, "Over the bridge!" cried Gandalf, recalling his strength. "Fly! This is a foe beyond any of you. I must hold the narrow way."

Gandalf and the Bridge of Khazad-dum -- Ted Naismith illustration

The "narrow way" is a metaphor used repeatedly by Macaulay to refer to the Tiber bridge defended by Horatius Cocles ("to win the narrow way") and ("scowled at the narrow way"). The term "narrow way" was familiar to Tolkien's generation of schoolboys from their recitations of "Horatius." Like Horatius with Herminius and Lartius, Gandalf held the "narrow way" flanked by his two companions--stalwart defenders Aragorn and Boromir.

Recitations in an American schoolroom of the 19th century

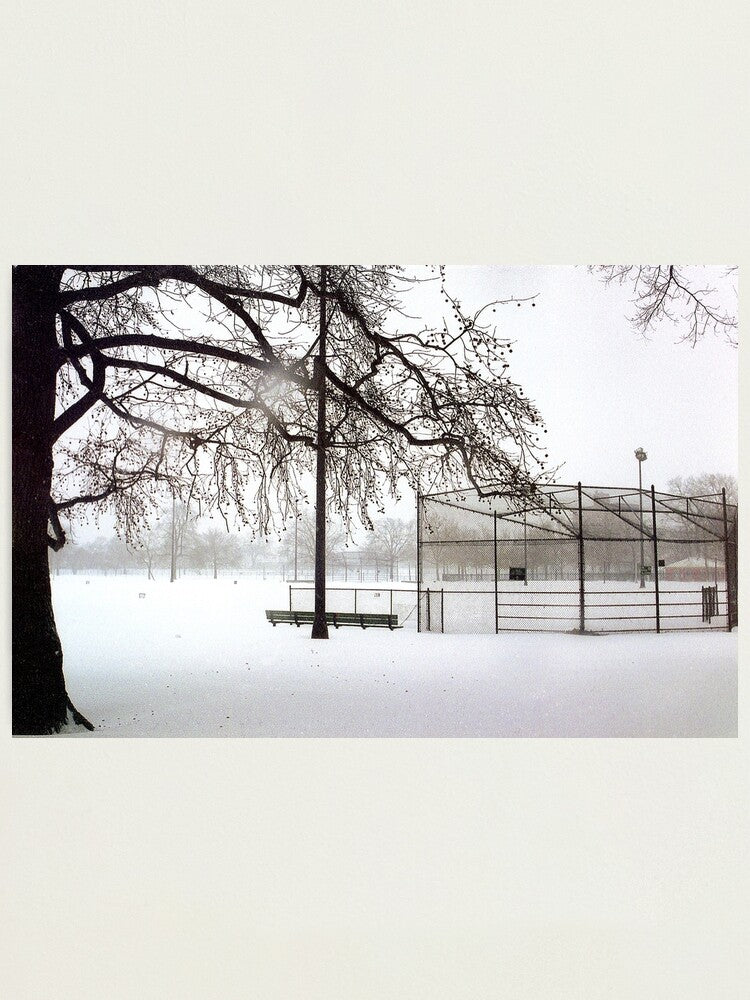

Ernest Thayer, born in 1863--too young to remember the Civil War--heard high school upperclassmen recite Macaulay's "Horatius" at Mechanic's Hall in Worcester. Thayer's "Casey at the Bat," published in classmate William Randolph Hearst's Examiner in 1888, took Macaulay's account of three brutal assaults against Horatius and his companions and turned it on its head, placing its heroes on the "base ball" field in baggy flannels rather than in burnished armor. In an ironic twist that many of Thayer's contemporaries recognized, the character and demeanor of the ill-fated batsman were patterned not on Horatius but on the Tuscan lord "Astur," the third of Macaulay's imagined champions to challenge the stalwart defenders of the bridge. As Horatius defeated Astur, so Thayer struck down the Mighty Casey and brought doom to Mudville. Thayer's enigmatic subtitle, "A Ballad of the Republic, Sung in the Year 1888," echoed Macaulay and signaled that his ballad evoked a contest far older than a forgotten strike-out on a remote ball field of small-town America.

Kurz & Allison print of the battle at Kennesaw Mountain, Georgia, June 27, 1864. Union Colonel Dan McCook, preparing his brigade for the assault, paced among the ranks quoting lines from Thomas Macaulay's poem "Horatius:" "And how can man die better / Than facing fearful odds / For the ashes of his fathers / And the temples of his gods?"

Kurz & Allison print of the battle at Kennesaw Mountain, Georgia, June 27, 1864. Union Colonel Dan McCook, preparing his brigade for the assault, paced among the ranks quoting lines from Thomas Macaulay's poem "Horatius:" "And how can man die better / Than facing fearful odds / For the ashes of his fathers / And the temples of his gods?"

So let's be clear about the use and misuse of the legend of "Horatius." The legend represents a memory of the defense of Rome's infant Republic against the power of tyranny. "Horatius" stands for the defense of a community insisting on self-government under the res publica -- a commonwealth of law rather than a kingdom dominated by the dictates, rages, or avarice of an overlord. Certainly people have risked their lives to defend the American Republic (among them were two of my great-great grandfathers, soldiers in Colonel McCook's brigade at Kennesaw Mountain). And patriots may be called upon in the future to defend the Republic with their lives. But it is a perversion of both history and legend to call upon citizens to die (and by inference, to kill) in a desperate attempt to sustain a position and power which the American people, by the deliberate exercise of their right to vote, have withdrawn from a president whose time in office is finished.

"Darkness is good: DIck Cheney. Darth Vader. Satan. That's power. It only helps us when they get it wrong. When they're blind to who we are and what we're doing." These oft-quoted words of Steve Bannon, who has posed as the ideologue and interpreter of Trumpism, make clear the forces he evokes -- and whose dark powers he prepares to unleash. Likewise, Bannon discloses the ultimate purpose of "what we're doing": power. If we were ever blind to or heedless of these signals, it is now time to pay attention to what Bannon says about his followers and their intentions: "It only helps us when they get it wrong--when they're blind to who we are and what we're doing."

"Horatius Cocles defending the Tiber Bridge," by Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641)

Horatius Cocles was half-blind -- he fought the battle with only one eye--yet he effectively countered the threat the Etruscans and their allies posed to the independence of Rome. Now in the light of day, we see clearly the forces that a defeated president and his allies are trying to summon, and the motivations that drive them. The example of Horatius does not support Steve Bannon's promotion of power for power's sake. Rather, Horatius is the protagonist of a different narrative--of the assertion of independence from tyranny, of the precedence of law above power; and of the right of citizens in a free community to participate in their own governance.

Now is the time to relearn--and reclaim--what the ancient legends taught America's founders, and to understand the true meaning of the inspiration drawn from those legends by the faithful defenders of our Republic.

Concord Bridge, April 19, 1775, by Don Troiani (b. 1949 ) American revolutionaries learned the example of Horatius from their reading of Roman historians such as Livy. History repeated itself at the North Bridge in Concord, Massachusetts on April 19, 1775. Minutemen from the Acton company, led by Captain Isaac Davis, Major John Buttrick, and Lt. Col. Robinson advanced toward British troops as smoke rose from the town center in the distance. Captain Davis fell in the first volley--but return fire from the militia precipitated the catastrophic retreat of the redcoats toward Boston.

Cover Photo: The Pons Fabricius across the Tiber in Rome, dating from 62 BCE, was completed following the consulship of Cicero and two years before the First Triumvirate of Julius Caesar, Crassus, and Pompey. The original bridge still stands near the former location of the wooden bridge defended by Horatius and his two companions.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.