Donald Hall on "Casey at the Bat:" A Ballad of the Republic

Educator, critic, and fourteenth United States poet laureate (2006-2007), Donald Hall (September 20, 1928 – June 23, 2018) penned an Afterword to the centennial edition of "Casey" [1] that best illustrates the peculiar American affinity for Thayer's immortal ballad. As to recent essays on the cultural significance of "Casey at the Bat" Caseyatthe.blog has awarded preeminence to A. M. Juster's "Casey at the Bat and Its Long Post-Game Show." But certainly no understanding of the place of "Casey" in American life is complete without Donald Hall's poetic insights, born of fond acquaintance from the days when his grandfather would recite the poem to him.

The mock-heroic meter and structure of the poem demands that it be recited to be fully enjoyed--and Hall's essay points out the importance of recitation in earlier eras, both in education and in popular entertainment. The phenomenon of recitation in the era preceding that of mass entertainment helped to explain some of "Casey's" popularity. Hall cited "many English sources" for "Casey:" old Scottish and English ballads (which Thayer learned from Professor Frank Child, their renowned collector) may have provided a framework, and W. S. Gilbert's Bab Ballads (by Thayer's own admission) provided Thayer an example of modern comic verse. Gilbert (of Gilbert & Sullivan) more importantly provided Thayer an example of a successful writer of light verse, which Thayer himself at one time aspired to be.

Yet neither old English and Scottish folk songs nor Bab's Ballads provided the heroic template underpinning "Casey's" enduring popularity. Confirming what we now know about Thayer's affinity for the ancients and his worldview grounded in Greek tragedy, Hall correctly perceived the poetic similes in "Casey" as "Homeric." That is the key insight into an understanding of how "Casey at the Bat" was understood in the 19th century--and for that insight alone, we can forgive Hall's missing Thayer's specific references to Thomas Macaulay's "Horatius."

Regarding the lasting success of "Casey," observed Hall, "There must be public reasons for public endurance." Hall cited reasons for this extraordinary endurance, literary and historical, especially calling attention to Thayer's elevation of ordinary language to describe universal sentiments. "Elevation is fundamental" wrote Hall,[2] and certainly this holds true if Thayer's intent was to frame such sentiments in a parody of a particular style of an epic poem, rather than as a mere send-up of modern heroes and their worshippers,

Hall noted the fitting nature of Casey's conclusion, in that "We require this failure" of Casey -- "but not all of us" he hastened to add, with an anecdote about his grandfather who could not accept Casey's downfall and tried to re-tell the story with a happy ending. Indeed, in this long-shelved centennial edition of "Casey at the Bat" that has emerged from the public library where most of my research was conducted, a disgruntled reader had in pencil amended the last line of Thayer's final stanza --where the sun is shining bright, and where children shout-- to read: "And that place is here in Mudville --mighty Casey hit it out!" In a real way, the ability to accept Casey's strike-out with grace and understanding is antithetical to modern America and certainly alien to modern sports culture. As Hall returned to this theme he insisted: "Casey's failure makes the poem." And so it does.

Here, then, in honor of this prolific poet rooted in New England's rocky soil--a worthy successor to Emerson, Longfellow, Dickinson, and Frost -- Caseyatthe.blog presents Donald Hall's 1988 essay "A Ballad of the Republic." And at the end, Hall adds an unexpected bonus. His "Afterword" explains the creative impulse behind his essay, and the method by which he captured it on paper.

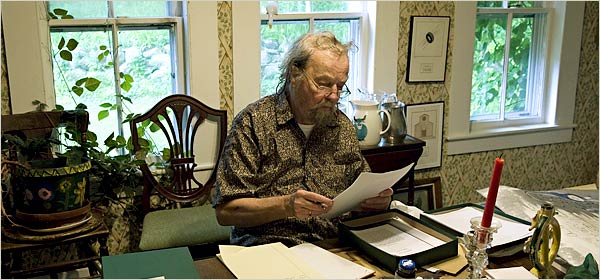

Donald Hall at Eagle Pond Farm in New Hampshire. His great-grandfather bought the house in 1865, and Hall wrote his first poems here at age 12. In 1975 he moved from Michigan back to the farm, where he lived with his wife, the poet Jane Kenyon, until her death in 1995.

Donald Hall at Eagle Pond Farm in New Hampshire. His great-grandfather bought the house in 1865, and Hall wrote his first poems here at age 12. In 1975 he moved from Michigan back to the farm, where he lived with his wife, the poet Jane Kenyon, until her death in 1995.

A Ballad of the Republic

Somewhere the sun is shining, and somewhere children shout, and somewhere someone is writing, "Casey at One Hundred." A century ago, on June 3, 1888, a twenty-five-year-old Harvard graduate, one poem poet Ernest Lawrence Thayer, published "Casey at the Bat" in the pages of the San Francisco Examiner. I suppose it's the most popular poem in our country's history, if not exactly in its literature. Martin Gardner collected twenty-five sequels and parodies to print in his prodigy of scholarship, The Annotated Casey at the Bat (1967; rev. 1984). Will the next Casey bat clean-up in the St. Petersburg Over-Ninety Softball League? Perhaps, instead, we will hear of a transparent Casey on an Elysian diamond, shade swinging the shadow of a bat while wraith pitcher uncoils phantom ball. Or spheroid, I should say.

Worcester, the industrial "Heart of the Commonwealth," in the 19th century

The author of this people's poem was raised in Worcester, Massachusetts: gentleman and scholar, son of a mill owner. At Harvard he combined scholastic and social eminence, not always feasible on the banks of the Charles. A bright student of William James in philosophy, he graduated magna cum laude and delivered the Ivy Oration at graduation. On the other hand, he was editor of the Lampoon, for which traditional requirements are more social than literary; he belonged to Fly, a club of decent majesty. It is perhaps not coincidence, considering Victorian Boston's social prejudices, that Thayer's vainglorious mock hero carries an Irish name. [Editor's note: Hall, who wore his education humbly, studied at Phillips Exeter Academy, Harvard (Class of 1951), Oxford, and Stanford. Like Thayer, Hall also graduated magna cum laude from Harvard].

After his lofty graduation, Thayer drifted about in Europe. One of his Harvard acquaintances had been young William Randolph Hearst, business manager of the Lampoon, expelled from Harvard for various pranks while Thayer was pulling a magna. The disgraced young Hearst was rewarded by his father with editorship of the San Francisco Examiner, where he offered Thayer work as humorous columnist. By the time "Casey" appeared, Thayer had left California to return to Worcester, where he later managed a mill for his father and studied philosophy in his spare time.

The Thayer residence at 67 Chatham Street on Crown Hill in Worcester is gone, but this neighboring Queen Anne house still stands

He received five dollars for "Casey" and never claimed reward for its hundreds of further printings. By all accounts, "Casey"'s author found his notoriety problematic. As with all famous nineteenth-century recitation pieces - "The Night Before Christmas," "Backward Turn Backward Time in Thy Flight" - other poets claimed authorship, which annoyed Thayer first because he did write it and second because he wasn't especially proud of it. There was the additional annoyance that old ballplayers continually asserted themselves the original Casey of the ballad: Thayer insisted that he made the poem up. The author of "Casey at the Bat" died in Santa Barbara in 1940 without ever doing another notable thing.

The poem's biography is richer than the poet's: At first "Casey" blushed unseen, wasting its sweetness on the desert air, until an accident blossomed it into eminence. In New York De Wolf Hopper, a young star of comic opera, was acting in Prince Methusalem. On August 15 [editor's note: the correct date is August 14], 1888, management invited players from the New York Giants and the Chicago White Stockings to attend a performance, and Hopper gave thought to finding a special bit that he might perform in the ballplayers' honor. His friend the novelist Archibald Clavering Gunter, recently returned from San Francisco, showed him a clipping from the San Francisco Examiner.

DeWolf Hopper gave the first performance of Thayer's "Casey at the Bat" at Wallack's Theatre in New York on the evening of August 14, 1888 -- Thayer's 25th birthday

In Hopper's autobiography, he noted that when he "dropped my voice to B-flat, below low C, at 'the multitude was awed,' I remember seeing Buck Ewing's gallant mustachios give a single nervous twitch." Apparently Hopper's recitation left everyone in the house twitching for joy, and not only the Giants' hirsute catcher. For the rest of his life, Hopper repeated his performance by demand, no matter what part he sang or played, doomed to recite the poem (five minutes and forty seconds) an estimated ten thousand times before his death in 1935. As word spread from Broadway, the poem was reprinted in newspapers across the country, clipped out, memorized, and performed for the millions who would never hear De Wolf Hopper. Eventually the ballad was set to music, made into silent movies, and animated into cartoons; radio broadcast it, there were recordings by Hopper and others, and William Schuman wrote an opera called The Mighty Casey (premiere 1953).

In December 1892, Hopper met Thayer at the Worcester Club after a local performance of the comic opera Wang --and a recitation of "Casey at the Bat"

When he first recited the poem, Hopper had no notion who had written it. Thayer had signed it "Phin.", abbreviating his college nickname of Phinny. Editors reprinted the poem anonymously or made up a reasonable name. When Hopper played Worcester early in the 1890s, he met the retiring Thayer - and poet recited poem for actor, as Hopper later reported, without a trace of elocutionary ability.

There are things in any society that we always knew. We do not remember when we first heard about Ground Hog Day, or the rhyme that reminds us Thirty Days Hath September. Who remembers first hearing "Casey at the Bat"? Although I cannot remember my original exposure, I remember many splendid renditions from early in my life by the great ham actor of my childhood. My New Hampshire grandfather, Wesley Wells, was locally renowned for his powers of recitation - for speaking pieces, as we called it. He farmed bad soil in central New Hampshire: eight Holsteins, fifty sheep, a hundred chickens. In the tie-up for milking, morning and night, he leaned his bald head into warm Holstein ribs and recited poems with me as audience; he kept time as his hands pulled blue milk from long teats. When he got to the best part, he let go the nozzles, leaned back in his milking chair, spread his arms wide and opened his mouth in a great O, the taught gestures of elocution. He spellbound me as he set out the lines on warm cozy air: "But there is no joy in Mudville - mighty Casey has struck out!" The old barn (with its whitewash over rough boards, with its spiderwebs and straw with its patched harness and homemade ladders and pitchforks shiny from decades of hand-labor) paused in its shadowy hugeness and applauded again the ringing failure of the hero.

If he had not recited it for me lately, I reminded him. He recited a hundred other poems also, a few from Whittier and Longfellow but mostly poems from newspapers by poets without names. I don't suppose he knew "Ernest Lawrence Thayer" or the history of the poem, but "Casey" itself was as solid as the rocks in his pasture. The word that left Broadway and traveled was: This poem is good to say out loud. Earlier, the same news had brought intelligence of Edgar Allan Poe's "The Raven" and Bret Harte's "The Heathen Chinee." Public schooling once consisted largely of group memorization and recitation. The New England Primer taught theology and the alphabet together: "In Adam's fall! We sinned all" through "Zacchaeus he! Did climb a tree! His Lord to see." Less obviously the Primer instilled pleasures of rhyme and oral performance. When we decided fifty and sixty years ago that rote memorization was bad teaching, we threw out not only the multiplication table but also "Barbara Frietchie." Recitation of verse was turned over to experts.

Earlier, for two hundred years at least, recitation and performance took center stage in the one-room schools; but it did not end there. In the schools, recitation-as-performance - not merely memorization to retain information - climbed toward competitive speaking, elimination and reward on Prize Speaking Day, when the athletes of elocution recited in contest before judges. The same athletes did not stop when school stopped, and recitation exfoliated into the adult world as a major form of entertainment. Hamlets and cities alike formed clubs meeting weekly for mutual entertainment that variously included singing, playing the violin or the piano, recitation, and political debate. In the country towns and villages, which couldn't afford to hire Mr. Hopper to entertain them (nor earlier Mr. Emerson to instruct and inspire them), citizens made their own Lyceums and Chautauquas. In my grandfather's South Danbury, New Hampshire, young people founded the South Danbury Debating and Oratorical Society. Twice a month they met for programs that began with musical offerings and recitations, paused for coffee and doughnuts, and concluded with a political debate, like: "Resolved: That the United States should Cease from Territorial Expansion."

While recitation thrived the recitable poem became a way of entertaining ideas and each other, of exposing or exercising public concerns. Poetry in the United States was briefly a public art. But after the Great War came cars, radios, and John Dewey; recitation departed, and poets have been blamed, ever since, for losing their audience. The blame is unfair, because the connection between poetry and a mass audience was brief, nor did it work for all poetry. John Donne never had a great audience; neither did George Herbert nor Andrew Marvell, nor in America Walt Whitman or Emily Dickinson. These poets made poems with a fineness of language that required sophisticated reading, and from most readers silent reading not to mention rereading.

All the same, some nineteenth-century poets wrote poems both popular and fine - without being as popular as baseball or as fine as Gerard Manley Hopkins. This moment was the fragile age of elocution. Some poets wrote variously - turning in one direction to talk to the people, and in another to talk to the ages. Longfellow's best work - the Divine Comedy sonnets, "The Jewish Cemetery at Newport" - is dense, sophisticated, adult poetry of the second order. But in his nationalist fervor he also wrote epics of the Republic's prehistory like Evangeline, or lyrics of the common life like "The Village Blacksmith." Making these poems, he made recitation pieces; without intending to, he wrote poems for children and for entertainment. When Whittier made "Barbara Frietchie" in his abolitionist passion, he made willy-nilly a patriotic poem to recite in schools. Meantime Walt Whitman - who had notions about poetry for the people - went relatively unread as he went largely unrecited. Mind you, he showed he could turn his hand to the recitation piece: "0 Captain My Captain" is poetically inferior to "Casey."

Thomas Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome (1842) was as popular in America as in England. "Horatius" was memorized and recited by young men who would fight the Civil War, and by Thayer's post-war generation as well

The twin phenomena of recitation and the popular poem thrived in England at the same time, and Macaulay's The Lays of Ancient Rome turned up on American school readers and on prize speaking days. The public Tennyson, laureate not melancholic, wrote verses often memorized for performance; lyrical Wordsworth and bouncy Browning served as well. There were many English sources, even for "Casey at the Bat": Thayer remembered looking into W. S. Gilbert's Bab Ballads before composing "Casey."

At my grammar school in the 1930s we memorized American poets: Whitman for "0 Captain My Captain," Joaquin Miller's "Columbus," something by James Whitcomb Riley. The trajectory of the recitation piece, of which "Casey" is a late honorable example, began its descent early. James Whitcomb Riley scored hits with "Little Orphant Annie" and others, but Riley was mostly hokum. Then there was Eugene Field, whose "Little Boy Blue" is gross sentimentality accomplished with skill; then there is Ella Wheeler Wilcox; then there is Edgar Lee Guest. (The Canadian Robert Service is a late recitable anomaly.) Vachel Lindsay and Carl Sandburg were themselves performers who seldom gave rise to performance in others; they led from recitation toward the poetry reading. There are poets today as sentimental and popular as Edgar Guest but they write free verse and no one recites them.

The tradition of recitation survives only in backwaters, like Danbury, in New Hampshire. If you come to our elementary school on Prize Speaking Day and sit in the school cafeteria-gymnasium-assembly, a miniature elocutionist may break your heart reciting "Little Boy Blue," or you may watch a stout tenyear-old outfielder, straight out of central casting, begin: "The outlook wasn't brilliant for the Mudville nine that day . .

Among the thousands of pieces memorized and recited, in the Age of Elocution, few survive. Why "Casey at the Bat"? For a hundred years this mock heroic ballad has lurked alive at the edges of American consciousness. It has endured past the culture that spawned it. When an artifact like this clownish old poem persists for a century, surviving not only its moment but its natural elocutionary habitat, there must be reasons. There must be public reasons for public endurance. We might as well ask: Why has baseball survived? Neither the Black Sox scandal nor the crash nor two World Wars nor the National Football League have ended the game of baseball. Every year more people buy tickets to sit in wooden seats over a diamond of grass - or in plastic seats over plastic grass, as may be. Doubtless we need to ask: Has baseball survived? Casey's game pitted town against town with five thousand neighbors watching. Maybe the descendant of Casey's game is industrial league softball played under the lights by teams wearing rainbow acrylics. These days when we speak of baseball we mostly mean the Major Leagues, millionaire's hardball, where our box seats place us half a mile from a symmetrical petrochemical field. Do we watch the game that Mudville watched?

"Do we watch the game that Mudville watched?" asked Donald Hall in his 1988 essay celebrating the centennial of "Casey at the Bat"

Yes.

As "Casey at the Bat" survives the culture of recitation, the game's shape and import survive its intimate origins. Not without change: If the five thousand ghosts of the Mudville crowd, drinking a Mississippi of blood to turn solid, reconstituted themselves on a Friday night at Three Rivers Stadium to witness combat between Cincinnati's team and Pittsburgh's, they would gape in spiritual astonishment at the zircon-light of a distant diamond under velvet darkness, at the pool-table green of imitation grass, at amenities of Lite, at the wave, at the skin color of many players, at tight uniforms, and at a scoreboard that showed moving pictures of what just happened.

But in their ectoplasmic witness they would also observe the template of an unaltered game. They would watch a third baseman move to his left, stopping the ball with his chest, picking the ball up to throw the runner out; or a second baseman flipping underhand to a shortstop pivoting toward first for the double play, or an outfielder charging a line drive while setting himself to throw. Above all, they would see a pitcher facing a batter late in the game with men on base. They would see a clean-up man approaching the batter's box with defiance curling his lip. "Casey at the Bat" survives -to begin with - because it crystallizes baseball's moment, the medallion carved at the center of the game, where pitcher and batter confront each other.

There are other reasons, literary and historical. When a poem is so popular, one needs to quote Mallarmé again, and observe that poems are made of words. "Casey" 's language is a small consistent comic triumph of irony. The diction is mock heroic, big words for small occasions: When a few fans go home in the ninth inning, they depart not in discouragement or disdain but "in deep despair." The remaining five thousand require a learned allusion: In his Essay on Man, Alexander Pope wrote that "Hope springs eternal in the human breast," and Thayer of course knew the source of his saw; but Pope like Shakespeare is largely composed of book titles and proverbs: Thayer uses Pope not as literary allusion but as appeal to common knowledge by way of common elevated sentiment.

Elevation is fundamental: Despite the flicker of hope, the crowd is a "grim multitude" - language appropriate to Milton's hell - and if the hero is mocked, hero-worshippers are twice mocked. Thayer's poetic similes are Homeric - as if Achilles faced Hector instead of Casey the pitcher. (If Casey is not quite Achilles, at least he is Ajax.) Imagery of noise, loud in Homer and his echo Virgil, rouses Thayer to exalted moments: A yell "rumbled through the valley, it rattled in the dell;! It knocked upon the mountain and recoiled upon the flat." This yell is cousin to the "roar! Like the beating of the storm waves on a stern and distant shore." It is noise again when Thayer's crowd reacts to a called strike: "'Fraud!' cried the maddened thousands, and echo answered fraud." These days at Fenway Park the bleacherites divide themselves for a rhythmic double chant, but they do not say "Fraud." When they feel polite they cry "Less filling" and echo answers "Tastes great."

Possibly crowds were not chanting "Fraud" in the 1880s either. It was a major form of Victorian humor to elevate diction over circumstance. Mr. Micawber soared into periphrastic euphemism to admit that he as in debt; W. C. Fields was an orotund low-comedy grandson. For a hundred years it was witty or amusing to call kissing osculation, and to refer to a house as a domicile. If somebody missed our tone, we sounded pompous, but usually people understood us: When we enjoyed something common or vulgar (like baseball) we could show a humorous affection for it, yet retain our superiority, by calling the ball a spheroid.

This habit of language has not entirely disappeared, but more and more it looks like an Anglophile or academic tic. The late poet and renowned advocate of baseball, Marianne Moore, always talked this way, never more than when she spoke of the game. When she identified the Giants' pitcher, "Mr. Mathewson," we are told that she noted: "I've read his instructive book on the art of pitching, and it's a pleasure to note how unerringly his execution supports his theories." Another St. Louis poet was T. S. Eliot, born the same year as "Casey," and like Moore expert in the humor of a polysyllabic synonym for a homely word. Eliot is the most eminent poet influenced by "Casey at the Bat." Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats includes "Growltiger's Last Stand," conflation of Custer and Casey, written in metrical homage and in allusion: "Oh there was joy in Wapping when the news flew through the land. . . ." Growltiger is a vicious fellow, racist or at least nationalist ("But most to Cats of foreign race his hatred has been vowed"), and loathed by felines of an Asian provenance. Absorbed in romantic adventure he is surrounded by a "fierce Mongolian horde," captured, and made to walk the plank.

Illustration by Errol Le Cain of T. S. Eliot's "Growltiger's Last Stand"

The author of Four Quartets and "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" grew up in the age of recitation; we could be certain that he knew "Casey" even if "Growltiger" were not written in homage. Like many poets he could write high or low, wide or narrow; unlike some poets, when he wrote for children he recognized that he was doing it.

Mockery is "Casey" 's point, with humor to soften the blow. After the crowd (which is us), the great Casey himself takes the brunt of our laughter. His name is the poem's mantra, repeated twenty-two times, often twice in a line: As he puffs with vainglory, "Defiance gleamed in Casey's eye, a sneer curled Casey's lip." The hero's role is written in the script of gesture. After five stanzas of requisite exposition, we catch sight of the rumored Casey in the sixth stanza: "There was ease in Casey's manner. . . ." By this phrase we are captured and the double-naming locks us in: "There was pride in Casey's bearing and a smile on Casey's face." We know the smile's message, and we know how Casey doffs his cap. Casey is Christlike: It is "With a smile of Christian charity" that he "stilled the rising tumult"; if we remember that this metaphoric storm occurs at sea ("the beating of the storm waves"), we may understand that Casey's charity earns its adjective.

And every time we hear "Casey at the Bat," the hero strikes out. We require this failure. Not all of us. My grandfather with his sanguine temperament always regretted that Casey struck out. He memorized the sequels and tried them all, especially "The Volunteer." In Clarence P. MacDonald's poem, printed in the San Francisco Examiner in 1908, the home team plays with no bench; behind in the game, it loses its catcher to an injury, and the captain calls for a substitute from the stands: A gray-headed volunteer finishes the game as catcher and his home run wins the game in the ninth. Besieged by teammates and fans to reveal his identity, the weeping stranger proclaims: "I'm mighty Casey who struck out just twenty years ago."

Wonderful.

But it won't do. None of the triumphant sequels will do. None show the flair of Thayer's ballad, its vigorous bumpety heptameter and mostly well-earned rhymes, or its consistently overplayed language. Most important, none celebrates failure. Casey may strike out: Casey's failure is the poem's success. When Thayer first published "Casey at the Bat" in 1888, it bore a subtitle seldom reprinted: "A Ballad of the Republic." Once we lived in heroic times: once - and then again. When we suffer wars and undertake explorations we require heroes, and Jeb Stuart must gallop behind Union lines, Lindbergh fly the Atlantic, Davey Crockett enter the wilderness alone, Washington endure Valley Forge, the Merrimack attack the Monitor, Neil Armstrong step on the moon, and U.S. stand for Ulysses S., Unconditional Surrender, and the United States.

Confederate prisoners watch Union Soldiers playing "base ball" during the Civil War

The Civil War, which ripped the country apart, began the work of stitching it together again. (One small agent of integrity was baseball, as blue and gray troops played the game at rest and even in prison camps, even North against South as legend tells us.) For five years North and South lived through the triumphs and disaster of heroes. Although nameless boys charged stone walls blazing with rifle fire, we concentrated our attention on heroic leaders, from dandified cavalrymen to dignified generals. Sons born to veterans, late in the sixties and early in the seventies, were christened Forrest, Jackson, Sherman, Grant, Lee, Bedford, Beauregard....

But hero-worship is dangerous and needs correction, especially in a democracy if we will remain democratic. To survive hero-worship we mock our heroes; if we don't we become their victims. Odysseus came home to slay the suitors; Ulysses S. allowed them to fatten on our larder: Heroic governance became disaster as the triumphant General turned into the ruinous President. Many other heroes struck out. When the romantic vainglorious George Custer, with his shoulder-length hair, made combat with Geronimo [editor's note: Custer fought Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, not Geronimo] in 1876, Growltiger walked the plank. Affluence and corruption, defeat and corruption bred irony. Violence of reconstruction and violence of anti-reconstruction eventually encouraged detachment from crowd passion.

Whatever young Thayer had in mind, writing his Ballad of the Republic, 1888 was a presidential year. We elected the mighty Benjamin Harrison president, a former officer of the Union Army, who took the job in a deal and installed as Secretary of State the notorious James G. Blame. De Tocqueville stands behind this poem as much as Homer does. Democracies choose figures to vote in and out of office - to argue over, to ridicule: We do not want gods or kings - that's why we crossed the ocean west - but human beings, fallible like us.

We pretend to forgive failure; really we celebrate it. Bonehead Merkle lives forever and Bill Maserowski's home run diminishes in memory. We fail, we all fail, we fail all our lives. The best hitters fail, two out of three at-bats. If from time to time we succeed, our success is only a prelude to further failure - and success's light makes failure darker still. Triumph's pleasures are intense but brief; failure remains with us forever, a featherbed, a mothering nurturing common humanity. With Casey we all strike out. Although Bill Buckner won a thousand games with his line drives and brilliant fielding, he will endure in our memories in the ninth inning of the sixth game of the World Series, one out to go, as the ball inexplicably, ineluctably, and eternally rolls between his legs.

"With Casey we all strike out," wrote Donald Hall. Illustration by P. J. Loughran for the National Pastime Museum

AFTERWORD to "A Ballad of the Republic" (by Donald Hall)

Baseball is my favorite pastime, and poetry my chosen work; when a publisher planned a centennial edition of "Casey at the Bat," it was not surprising that my name came up. Barry Moser painted the pictures, and I wrote the "Afterword" for Casey at the Bat: A Centennial Edition (1988). To prepare for the essay, I read the poem over many times, took notes about my associations with the poem, and pondered the history of recitation. I read Martin Gardner and others about Ernest Lawrence Thayer, De Wolf Hopper, and the poem's popularity. "Casey" 's subtitle led me to political or social notions, relating the poem to the gilded age. Notes, notes, notes. Putting my notes in order, I made a quick and dirty first draft (many writers do a slower, more nearly finished first draft, because it works best for them; not for me) and a laborious second draft (order; focus; cutting) and seven or eight further drafts. My drafts became easier as the essay progressed; they became mere tidying. Before book publication, I sold this essay to the New York Times Book Review; it was too long for the space available, so they cut it -removing with deft precision anything that resembled an idea. My problem in writing this piece, which was also my opportunity, was the amalgamation of many different subjects into one essay. I arrived at my structure by discovering transitions - ways to move from place to place by legitimate association or by turn of phrase, in order to make one discourse out of literary criticism, biography, social and historical ideas, anecdotes of education, personal reminiscence, popular cultural history, and psychological speculation. To move from an account of the poem's popularity to the history of recitation was easy (paragraph 8); then I could move to reasons for reciting this poem (paragraph 16) which allowed me scope to speak of its language and its cultural or historical implications; finally -from history to the individual - I could speculate on "Casey" and the American psyche. The structure pleases me, when I look at the essay again. A poem that I enjoy became an excuse for me to revisit things - baseball, recitation, American history, and grandfathers - that I like to write about.

Donald Hall at work at Eagle Pond Farm. In 2010, Hall received the National Medal of Arts from President Obama

[1] See Donald Hall, "Afterword" to the Centennial Edition of "Casey at the Bat," illustrated by Barry Moser (Boston: David R. Godine, 1988, pp. 23-32.

[2] Hall, ibid., pp. 28-29.

#CaseyattheBat #BalladoftheRepublic

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.