The Ballad of Sam Winslow

Painting of Samuel Ellsworth Winslow (1862-1940) by American artist Graig Kreindler (1980 - ) Winslow could hit for power, but for which on-field achievement was he remembered by his 1885 classmates--including Ernest Thayer?

Who was Casey, anyway? That speculation has intrigued cultural historians, scholars and aficionados of the early years of baseball, and generations of fans of "The Mighty Casey." And there are legions of civic boosters in California and Massachusetts still debating whether Stockton or Holliston is the true "Mudville." Even from the poem's origin in 1888, readers speculated that "Casey" was in fact a poetic pinch-hitter for Mike "King" Kelly--perhaps the most famous (and certainly the best-salaried) player of the era. But Thayer himself, when quizzed about the inspiration for his baseball ballad, was known most often to say the name "Sam Winslow."

Baseball Hall of Fame's Mike "King" Kelly (1857-1894) is often cited as the model for Thayer's "Casey at the Bat" though Thayer himself dismissed the claim. It is likely, however, that Thayer had seen "$10,000 Mike" compete for the Giants when they played exhibition games in California in the fall of 1887.

The role of Samuel Ellsworth Winslow--Ernest Thayer's boyhood pal, classmate at Harvard, and captain of the Harvard nine--in the origins of "Casey at the Bat" has remained one of the unsolved mysteries of the ballad deemed by poet A. M. Juster "the most enduring poem of American popular culture." Now with the gracious assistance of Sam Winslow's granddaughter and great-grandson, the honor paid by "Phinney" Thayer to his esteemed friend has come into clearer focus. "Casey at the Bat" can now be understood as a tribute to the young Sam Winslow and his baseball prowess--but not in the way we have always imagined. And as we unravel the tangled threads of this story, we gain new insights not only into Thayer's creativity but also into how the ballad of "Casey" resonated with those who knew Winslow best--the Harvard Class of 1885.

Holmes Field, 1880's - venue of the epic home games of the Harvard nine

During the last decade as I researched the background of "Casey at the Bat" and the obscure life of "Casey's" self-effacing author, I puzzled at Thayer's reference to Sam Winslow whenever the former was questioned about the origins of The Mighty Casey. So how did Thayer's boyhood pal and college classmate figure into the legend of “Casey at the Bat”? Was there something more to Thayer’s references to Winslow than their lifelong friendship-- and Thayer’s admiration for Sam's baseball exploits—would suggest? After all, "Casey" would enter the pantheon of American folk tales as a tragic, or even tragi-comic figure depending on how seriously you take the role of sports in American culture. But Sam Winslow was not one to disappoint, as did Casey--for Sam captained his team from victory to victory, ultimately to the Intercollegiate Championship of 1885. If Winslow was eulogized in the ballad of "Casey," then why and how?

I hoped when I began research for this project that somehow there might emerge a previously undiscovered historical reference or hitherto unknown connection to Thayer or one of his circle. Then fate intervened when I replied to an e-mail that had been sitting in the inbox for Caseyatthe.blog -- my on-line vehicle for sharing these meanderings along the by-ways of the Gilded Age. John Winslow Peters introduced himself as Winslow's great-grandson, and responded to my follow-up with new information and documents. Would I like to talk to his Aunt Dorothy? he asked. Sam Winslow's granddaughter, said John, is now living in Hawaii enjoying the tenth decade of life, and would be happy to share her memories--as clear and detailed as ever. [At age 93, in 2025, Dorothy still resides in Honolulu].

In his last decade Thayer would add more nuance to the public version of how the "Casey" ballad emerged from his youthful imagination. But there is no doubt that Thayer's boyhood friend and classmate provided Thayer a vivid template of a modern hero. Son of a renowned New England family, who went on to serve as a Massachusetts Republican party leader, U.S. Congressman, and chairman of the United States Board of Mediation, Sam was above all "a born leader" as his classmates remembered him.

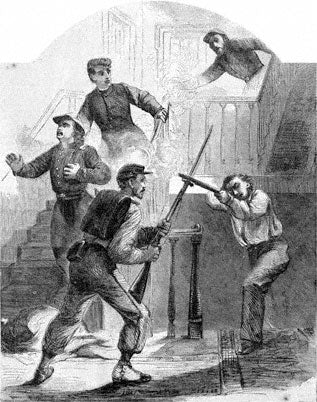

Illustration from the Fall River Daily Evening News, March 10, 1893

Samuel Ellsworth Winslow (April 11, 1862 - July 11, 1940) had graduated a year earlier than Ernest from the Classical & English High School in Worcester. His father--also Samuel--was a manufacturer of skates in Worcester and also served as Mayor from 1886 to 1890. Samuel, Jr. spent a year at the Williston Seminary in Easthampton before joining Thayer at Harvard as a freshman in 1881. "A born leader," as Thayer described him, Sam was one of thousands of young men born during the early years of the Civil War with the first or middle name, "Ellsworth." Never was a name of honor more aptly bestowed on a boy born in 1862.

Colonel Elmer Ellsworth (1837-1861) was a remarkable young man who clerked in Lincoln's Springfield law office, assisted Lincoln's 1860 Presidential campaign, and recruited and trained one of the first elite volunteer units in the Union army, the "Fire Zouaves," New York's 11th Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Killed in a May1861 skirmish in Alexandria (just across the river from Washington, D.C.) and mourned not only by the Lincoln family but by Unionists throughout the North, Ellsworth was the first well-known casualty of the Civil War.

Death of Colonel Ellsworth, from sketch in Harpers Weekly, June 15, 1861; courtesy of the Gilder Lehman Collection, New York (#GLC 00623)

Historian Adam Goodheart, diligently searching the 1880 census via Ancestry.com, identified over 20,000 Americans born during the Civil War with the first or middle names of "Elmer," "Ellsworth," or "Elsworth." Goodheart estimates that if anything, this figure, like the census itself, represents an undercount.

Goodheart observed of Ellsworth's fame before the War: "Never before had any American become famous and adored not for any particular accomplishments--not for being a poet or an actor or a war hero--but simply for his charisma." After his death, a shattered Lincoln mourned as Ellsworth's body lay in state in the East Room of the White House. For the Union at large, "Ellsworth's death released a tide of hatred, of enmity and counterenmity, of sectional bloodlust that had hitherto been dammed up....It was Ellsworth's death that made Northerners ready not just to take up arms but actually to kill."(3)

J. Lee Richmond, Brown University pitcher and Major League star who spun the first perfect game in 1880

The Worcester Connection

As students at Worcester's Classical and English High School, Sam and Ernest would have been awed by the local achievement of the remarkable J. Lee Richmond, who had led the Brown University base ball team to the intercollegiate championship in 1879. As a graduating senior playing for the Worcester base ball franchise in 1880 (the rules separating amateur and professional play then not yet in effect), Richmond took a train on June 2 from Providence to Worcester, arriving in time for the Worcesters' afternoon game with the Cleveland Blues at the Agricultural Fairgrounds. In a dramatic 1-0 contest, Richmond employed his baffling left-handed fastball, curve and drop ball to pitch professional baseball's first perfect game. If young Winslow had required a role model for his own pitching aspirations, he would need to look no further than his own home town.[5]

Class of '85 freshman nine, on the steps at Harvard's Matthews Hall in the spring of 1882.. Pitcher Winslow is seated on the second step, front row left. Seated next to him on the fourth step is Jack Follansbee, a pal of Will Hearst. Behind Follansbee, standing with his hand pulling at his jacket, is Roland Boyden. After graduation, as a renowned attorney, Boyden would help confirm Thayer's credentials as author of "Casey," and would assume the honor of reciting the poem at class reunions well into the 20th century.

Class of '85 freshman nine, on the steps at Harvard's Matthews Hall in the spring of 1882.. Pitcher Winslow is seated on the second step, front row left. Seated next to him on the fourth step is Jack Follansbee, a pal of Will Hearst. Behind Follansbee, standing with his hand pulling at his jacket, is Roland Boyden. After graduation, as a renowned attorney, Boyden would help confirm Thayer's credentials as author of "Casey," and would assume the honor of reciting the poem at class reunions well into the 20th century.

By the time he entered Harvard, Sam's athletic skills already qualified him to captain the freshman nine in the spring of 1882. Behind Sam's pitching, the freshman squad compiled a more-than-respectable record of 6 wins in their 8 games played. Based on his early signs of prowess, the varsity team called on Sam to pitch against the New York Metropolitans, a professional club, on May 30, 1882. Even though Harvard lost 12 - 4, Sam must have felt a foretaste of future glories as he pitched before a crowd at the New York Polo Grounds.

Then in his sophomore year, Winslow was called to the varsity squad -- though primarily as a bench warmer. Sam would have needed his reserves of patience as pitching duties were apportioned among junior J.A. White ('84) and freshmen Nichols and Allen, who often played as a battery, exchanging pitching and catching roles. From the sidelines, Sam watched the freshmen Nichols and Allen pitch, as the 1883 nine scratched out a modest 12-15 record for the season. Of six games played against arch-rival Yale, the outmatched Crimson lost five and tied one.

Winslow was called from the bench as the season drew to a close, winning 2 games and losing 3. He was chosen to pitch the final game of the year, an exhibition against Yale at Philadelphia for the holiday weekend of July 3, 1883 -- but the outcome was a disappointing 24 - 9 loss to their Eli rivals.

But in 1884 the team started to come together. Up-and-coming sophomore Edward "Nick" Nichols split pitching starts with Winslow, who hurled memorable victories against Princeton, Yale (in New Haven), and Dartmouth. Overall, Winslow pitched nine complete games with a record of 5 - 4; while Nichols started in five with a record of 4 - 1. In addition, Winslow and Nichols shared pitching duties in eight games, rotating between the pitcher's box and center field--a successful strategy achieving a joint record of 7 - 1. Nichols and Boyden split pitching roles in a shutout win against Williams on May 30. In the last regular season game before the epic tie-breaker against Yale in Brooklyn, Winslow pitched against Yale in New Haven in a 6-2 Harvard loss.

At the end of the season, with Harvard and Yale tied in the league standings; a final game to decide the championship was scheduled on June 27 at Washington Park in Brooklyn, New York.

Washington Park in Brooklyn, 1887, from beyond right field

At least 3,000 spectators were in the stands when the game commenced at 4 pm. Nichols was tapped for pitching duties, allowing only four runs (one on a wild pitch), but the Harvard bats were stifled. With the score Harvard 2, Yale 4 in the eighth inning, Harvard loaded the bases with no outs, but the Yale pitcher pulled himself together. Good defensive play allowed Yale to escape the inning and pocket the Intercollegiate Championship--a bitter ending for the Harvard Nine, who had beaten Yale twice during the regular season. All agreed however, that the championship game was one of the most exciting games ever played, or witnessed, in college baseball.

Look closely at the somber faces in the official portrait of the '84 squad (below). Even though they had lost the championship, the seeds of victory were being sown: the stage had been set for one of the most significant years in college baseball competition.

The official portrait of the 1884 Nine, posed on the steps of Matthews Hall, captures a somber mood--perhaps reflecting the disappointment of losing the championship match to Yale in Brooklyn on June 27. Winslow is the second man seated on the right railing, immediately behind Allen, the catcher, who is identifiable by the mask perched on his left knee. The lanky Nichols, pitcher of record in that epic championship game, would dominate the Intercollegiate competition the following year. He stands in the center of this photo, his hands resting on the shoulders of his teammate.

Contrast the casual postures and expressions in this photo of the 1884 Yale squad to that of the Harvard nine, above. The impression conveyed is one of consummate satisfaction -- most likely following the team's victory over their rivals in the epic June 27 championship game.

During the summer of 1884, before his senior year, Sam worked on his form by pitching for the Barnstable Cummaquids on Cape Cod.

In the fall of 1884, the opening of the senior year for Winslow and Thayer, a serious football injury to Phillips, the captain of the baseball nine, led to Winslow's selection as substitute captain. Thereafter Sam's true genius as a trainer and organizer manifested itself. During the winter, Winslow drilled the team not only in the indoor batting cage, but also introduced cross-training in the form of handball practice--no doubt enhancing the team's defensive speed and agility. As spring arrived, Winslow set up nets outside which served as backstops for batting practice, and insisted on extra workouts in accordance with his maxim, "Batting wins ball games."

As he assumed the role of manager in the fall of 1884, Sam recognized that he and Nichols would need to share time "in the box," as the pitcher's area was referred to in those days. It was the right choice, and a key to the team's success. With his "rifle-shot" delivery and baffling curves, Nichols dominated the opposition.

The outlook for the 1885 campaign looked auspicious when Harvard won its first seven games, scoring an average of ten runs per game. Then on May 4 the tough Cochituate amateurs came to Cambridge and embarrassed the Harvard nine by holding them to one run, while scoring three. Winslow then demonstrated the maturity and creativity of his leadership by engaging the Cochituates' superb pitcher, a man by the name of Bent, to pitch to the Harvard team each afternoon until the batters learned how to hit his best stuff. (Certainly Nichols and Winslow would also have appreciated and practiced Bent's technique!) By the time of the game with Yale in New Haven on May 16 (won by Harvard 12-4), the Harvard batters confidently intimidated the opposition.

Harvard President Charles W. Eliot ( 1834-1926 )

Winslow, a year older than most of his classmates, turned twenty-three in the spring of 1885. He took his responsibilities as coach, trainer, and player equally seriously and was not afraid to suspend one of his best players on June 12, with crucial games approaching, for an infraction of training rules. Because this sort of discipline had never been imposed on players at Harvard, college President Charles Eliot called Sam into his office for a chat. As recalled years later by one of Sam's classmates, Eliot opened the interview by asking Sam why he had taken such extreme measures to suspend a teammate. Sam, not at all intimidated, patiently explained the circumstances and his reasons, after which Eliot exclaimed, "Winslow, you did just right, and you deserve to win!"[4]

"Curves: Bothering the Batsmen in These Modern Scientific Days," from the New York Sun, reprinted in San Francisco Examiner 17 July 1887

Winslow's nine clinched the conference championship in Cambridge in a close game with Brown on June 15 (from which Winslow had excluded the disciplined player). Nichols struck out 20, though the game was tied at 2 going into the ninth inning (in those days the order of which team batted first was determined by coin toss).

Finally Harvard pushed over a run to win the game--and to clinch the championship. In the ten conference games which counted for the trophy, Nichols also batted an even .500 as the top hitter for the club.

Dr. Edward Hall Nichols, former pitcher for the '85 Harvard nine, is in the center of this photo. After his service as a surgeon during the World War in France, Nichols took on the role of team doctor for Harvard football. In this undated photo (ca 1919-1922), he appears with the legendary coach Robert T. Fisher (Harvard Class of 1912), on the left. Fisher took the Harvard eleven to the Rose Bowl on January 1, 1920, defeating Oregon 7 to 6. On the right is Major Fred W. Moore (Harvard Class of 1893, Harvard Law 1896), who was Graduate Athletic Treasurer for 13 years. In his school years, Moore managed both the Freshman and Varsity football teams (Harvard University Library, Digital Collections).

Thereafter, the Harvard men were unstoppable on the way to a record of 27 and 1 for the year, with a massive celebration in Harvard Square and in the Yard following a second victory over Yale on June 20.

Harvard - Yale game in progress, June 20 1885, Holmes Field, Cambridge. An estimated 6 to 8,000 spectators were in attendance, including at least 1,500 women. Harvard prevailed 16-2.

Following graduation, Sam toured Europe--as did Thayer and other classmates--but unlike Thayer, who preferred the temperate climate and genteel urbanity of France and Italy, Sam spent months abroad appreciating the Nordic splendors of Sweden, Norway, and Finland as well as the less-traveled destination of Russia. On his return to Worcester, Sam was appointed Secretary and Clerk of the family skate company, then chief operating officer a year later. He also threw himself into local, then Commonwealth politics with the same vigor with which he had once captained the Harvard nine. He managed his father's successful campaigns for Mayor, chaired the Republican Committee in Worcester, and by age 31 had been chosen to helm the state Republican Committee. In 1889 he married the elegant Bertha Russell, an accomplished violinist, and the following year was appointed by Governor John Brackett to his staff, with the title of "Colonel." Though the rank of Colonel appears to have been more honorific than military, Winslow treasured and retained this title for the rest of his life (evoking another parallel with his renowned namesake, the heroic Colonel Elmer Ellsworth).

Samuel Winslow Skate Manuacturing Co. poster ca 1895

Sam would go on to serve five terms in the U.S. Congress, after which President Coolidge appointed him to the U.S. Board of Mediation, which Sam chaired until his retirement in 1934. Setbacks and disappointments in Sam's life were few but noteworthy. In 1896, Winslow campaigned unsuccessfully for the Republican nomination for the office of Lieutenant Governor--which at that time was considered a stepping-stone to the governorship of the Commonwealth. In fact, the man who instead of Winslow was given the nod for that position, W. Murray Crane, did go on to become Governor in 1900. Then in 1916, son Sam Jr. dropped out of Harvard after his junior year to wed the lovely Edna Burns, bookkeeper for one of the Harvard Square bookstores. In the wake of his parents' disapproval of the secret marriage, Sam Jr. and his bride took up their new life in Maine, where Sam worked in a leather factory. It was not the life young Sam had been born into, and in which he was expected to follow in his father's footsteps, but it was a life to which his heart had led him. And most importantly, the couple were happy. "If only we had remained in Maine..." Dorothy would recall her mother's lament in later years.

But whether out of charitable forgiveness or grudging acceptance of his son's choices, Sam Sr. journeyed to Maine to ask Sam, Jr. to bring Edna with him back to Worcester, where a son, nicknamed Duggie, and daughters Ann and Dorothy were born. Dorothy retains happy memories of her playful, charming father with his "movie-star smile" in their old, brown house in Worcester, where Sam Jr. had taken a role in the family business. But circumstances would propel the family on a contrary path. The great crash of 1929 brought down the Winslow skate empire, and in the aftermath of misfortune, Sam Jr. charmed his way into another relationship and another marriage. Duggie went to live with his father, and Dorothy, Ann. and Edna were on their own in Dorchester. The Winslow grandparents, who had never fully reconciled with their son's life choices, began to lapse into an austere distance. Perhaps the uncompromising rectitude exemplified in Sam Sr.'s role as star and manager of the Harvard team--and as carried forward into Republican politics--may have also made it difficult to deal with the unpredictable complexities and compromises of family life.

Stonewall Farm, the Winslow estate in Leicester, formerly the Joshua Clapp House. Dorothy visited her Winslow grandparents here in the summer of 1936

In the summer of 1936, Edna was hospitalized for surgery. For several weeks, while she recovered, the two girls had to be farmed out to relatives. On the afternoon he delivered twelve-year-old Dorothy to the family mansion in Leicester, her father grew uncharacteristically silent as they approached the estate. After a brief word to his mother on the columned portico and a kiss to Dorothy, her “trickster” father was again absent—both "There and Not There"--as she would later title a poem about him. Dorothy was on her own to explore the dozens of rooms along dark mirrored corridors, to peek into the windows of an abandoned greenhouse, and to tap tunes on the xylophone in her grandmother's music room.

Dorothy Winslow Wright, Sam Winslow's granddaughter, in a 2011 photo.

"When I was five years old, I stood in front of my strong rotund grandfather, Sam Winslow, my nose about 6 inches from his belly. We were on the grass in front of the family home at Stonewall Farm, Leicester--my regal grandmother ("Lady GaGa" to us) standing stiffly beside him.

When the Colonel spoke, his voice thundered and I thought, "What a powerful man"…yes, he really could have been the hero of "Casey at the Bat."

--Dorothy Winslow Wright, June 6, 2022

On the phone from her independent living community in Hawaii, Dorothy recited the poem she had written about those summer days with the Winslows. In our own time, it is hard to imagine a world in which children did not expect to dominate every social situation like the ringmasters of a Barnum & Bailey circus. But to view the world of the 1930's through the eyes of an awkward twelve-year-old, sitting in the presence of her distinguished grandfather and her glamorous grandmother, the elders tinkling the ice in their glasses and conversing about politics, was an experience I can only describe as time-travel. Here in the “velvet-curtained library” Sam and Bertha entertained the political and literary luminaries of their time and place – no doubt including Sam’s lifelong pal “Phinney” Thayer, who himself had moved from Worcester to Leicester in 1899.

--“Stonewall Farm,” by Dorothy Winslow Wright in There and Not There (Koloke Press, 2006)

As for politics, 1936 was a national election year so there would have been much for Sam and Bertha to discuss that summer evening. Roosevelt was seeking re-election based on the New Deal measures his administration had implemented, and by 1936 FDR no longer felt the pressure from the populist left represented by the late Huey Long--U.S. Senator and former Governor of Louisiana who had been assassinated the previous fall. In Cleveland in June, Republicans had nominated Kansas governor Alf Landon as candidate for president and Chicago newspaper publisher Frank Knox as his running mate. To a Yankee family like the Winslows, the noteworthy feature of the Republican convention was the fact that the major contenders for the nomination were from states west of the Mississippi. For Sam’s generation, descended from colonial governors dating back to the Mayflower, the globe idly spun by Dorothy in the corner of the library was changing swiftly.

The esteemed Sam Winslow as he would have appeared to his granddaughter Dorothy ca 1936

But a more likely topic for after-dinner conversation at Stonewall Farm would have been the impending primary contests in the Commonwealth --in particular the race for a vacated U.S. Senate seat. The colorful (and blatantly corrupt) James Michael Curley, who would dominate Boston and Massachusetts politics up to mid-century, had decided not to seek re-election as Governor. Instead he would put himself forward for the U.S. Senate--a fearful prospect for all Yankee Republicans. But Sam Winslow would have favored a young contender for the Republican nomination--Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., Harvard Class of '24, first-term representative to the Massachusetts House. Lodge would go on to defeat Curley in November during an otherwise national Democratic landslide. Except for time spent in the service of his country during World War II, Lodge would represent the Commonwealth in that Senate seat until defeated in 1952 by John F. Kennedy (Harvard Class of 1940).

The Bancroft Hotel in Worcester, where Sam and Bertha moved after the hurricane of 1938

The Bancroft Hotel in Worcester, where Sam and Bertha moved after the hurricane of 1938

Dorothy and Ann would soon rejoin their mother, her health restored. But the memory of that summer evening in the Winslows' library would linger into the 21st century. Dorothy would visit her grandparents only once more, after the Hurricane of '38 had wrecked the mansion at Stonewall Farm, and Sam and Bertha had relocated to the Bancroft Hotel in Worcester. There in July of 1940 Sam would expire only weeks before Ernest Thayer, in California, would join him in the Elysian fields of baseball glory.

Sam Winslow's Baseball Legacy

Ernest "Phinney" Thayer (1863-1940) -- Harvard University Archives

So how did Sam Winslow figure into the legend of “Casey at the Bat”? as the twentieth anniversary of the poem approached, and as Thayer and his classmates Lent and Boyden helped to quell the outbreak of false authorship claims, Thayer began to open up regarding the origins of the poem. And as "Phinney' put it to journalist Homer Croy, in an interview published in Baseball Magazine in October 1908:

"...It was only on account of my friend, classmate, and associate on the Lampoon, Sam Winslow, that I became interested [in baseball]. Naturally, as Sam was captain of the nine--one of the best nines that Harvard ever had--that I felt stirred. I scribbled 'Casey' during May, 1888, and it was published in the Examiner on June 3, 1888."[6]

If Thayer intended to immortalize Winslow in the ballad of "Casey," as I now believe he did, then in what manner did the poet model the protagonist? For Thayer's ballad was no mere bit of newspaper doggerel as detractors have claimed: its subtitle "A Ballad of the Republic" evoked a deeper layer of literary and historical context. But at least as regards baseball, Thayer's lifelong reference to classmate Sam, the intrepid captain of the nine, concealed something of an inside joke which only the graduates of the Class of '85 could fully appreciate.

Following an exchange of correspondence after John Peters had connected me to his Aunt Dorothy, John forwarded some ephemera of family history that have survived the transit of time. One of these items was a tribute page clipped from a Class of '85 alumni publication—likely from the third triennial reunion in 1894 or the 10th reunion in 1895. The class of ’85 would never forget the legendary exploits of their classmate Sam. But what in particular did they remember about their intrepid comrade and captain?

Photo page from Class of 1885 alumni publication, undated; courtesy of Dorothy Winslow Wright. Winslow is featured here as "The Crimson's Star Pitcher."

Here was a clue along the path I was following. Although Sam's major contribution to the Inter Collegiate championship of '85 had been as manager, trainer, motivator and disciplinarian, he was chiefly remembered by his peers as a talented twirler (see caption, "The Crimson's Star Pitcher," above).

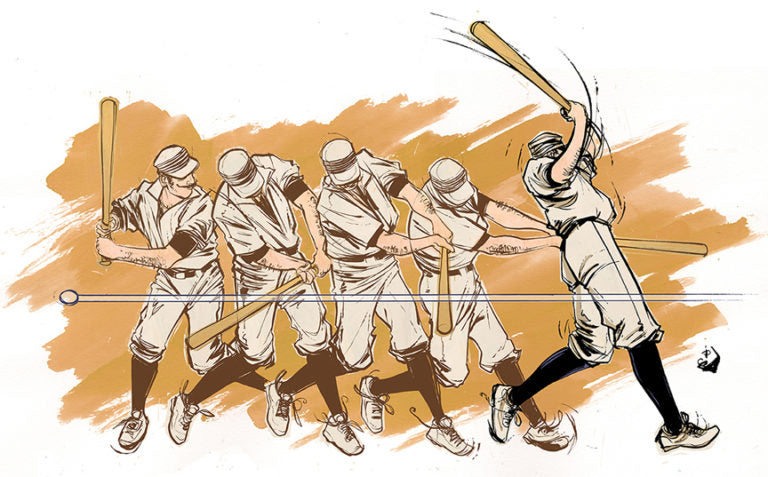

More evidence of Sam’s renown as a pitcher has come from his granddaughter Dorothy-- an excerpt from Albert B. Southwick’s Once-Told Tales of Worcester County. Formerly the head editorial writer for the Worcester Telegram & Evening Gazette, the prolific Southwick--also a Leicester native--as of last summer was still contributing columns on local history to the newspapers at age 100. In a chapter on Worcester’s prestigious baseball history, Southwick further elaborated the legend of Sam Winslow, who in his appearances as a Harvard pitcher added drama to the role that Nichols otherwise filled with machine-like precision. Sam perilously loaded the bases in the ninth inning on three separate occasions, though in each instance retired the final batter for the victory. “The image of Winslow snatching victory from [the jaws of] defeat at the last minute stayed with Thayer,” wrote Southwick—and undoubtedly created lasting adrenalin-charged memories for the Harvard partisans of the era.

One of the less-appreciated delights of Thayer’s “Ballad of the Republic"-- his subtitle to “Casey at the Bat"-- was the way in which Thayer had drawn the heroic figure of the doomed batsman from an ancient ballad dating to the birth of the Roman Republic in 509 BCE. This venerable tale, versified by English parliamentarian Thomas Macaulay in 1842 as “Horatius,” became known in America as "Horatius at the Bridge." Much beloved by the Civil War generation, this ballad made Macaulay’s Lays of Ancient Rome a best seller in America and its hero a template for the self-reliant brand of heroism once lauded by Emerson and then demanded by the extremities of the Civil War.

Cover of 1881 edition of Lays of Ancient Rome by Thomas Macaulay, with artwork by J. R. Weguelin (1849-1927)

Consistent with Thayer's sly and subtle brand of humor, the character of the doomed batsman Casey was traced upon the third--and last--of the Etruscan champions to confront Horatius. Here on the apron of a narrow wooden bridge across the Tiber stood the captain of the Roman guard with two stalwart companions -- posing the last barrier to the overwhelming might of an army summoned to crush the upstart Roman Republic. Casting scornful glances upon his cowering countrymen, and smiling serenely upon his foes, Astur of Luna strode confidently to the bridgehead, whirling his broadsword above his head. Minutes later, like Casey, Astur lay vanquished in the dust.

Death of Astur, by J. R.. Weguelin, illustrated in 1881 edition of Lays of Ancient Rome

Thayer, Winslow and their high school classmates all knew the legend of Horatius. Many of them had learned to recite Macaulay's poem by heart in competitions at Worcester's Mechanics Hall. They understood Casey's bravado as he approached the plate in Mudville--it was the same hubris that had undone the noble Astur before the gates of Rome. And they knew also that the true hero of the ballad of "Casey" was the man in the pitcher's box--the intrepid Sam Winslow, captain of the Nine, standard-bearer of Harvard tradition and of the Republic which Winslow would go on to serve.

In this way Ernest Thayer paid tribute to Sam's role in those memorable late-inning strikeouts--but as the bold and crafty pitcher, not as the hubristic batsman. As a writer whose humor was steeped in pathos--a quality admired and shared by fellow Lampoon contributor George Santayana (Class of 1886)--Thayer was the ideal chronicler to elevate a lost baseball game to the status of epic (although with the likely unintended consequence of promoting The Mighty Casey to the pantheon of American folk heroes). And though Thayer could not expunge the outcome of the dramatic Harvard -Yale contest of 1884, through artistry he could assuage the bitterness suffered by the Crimson partisans at the game in Brooklyn--concluding, as would the Mudville showdown, on the short end of a 4-2 score. Look again at the 1884 Harvard team portrait above, and you will see evidence of emotions--disappointment, regret, denial, defiance-- lingering on the faces of the contestants. But never defeat. From that cathartic moment in 1884 the immortal championship of 1885 would be fashioned.

Special thanks to John Winslow Peters and Dorothy Winslow Wright for family memories and documents, and especially to Dorothy for her poetry collection inspired by her childhood memories, interpreting the lives of her parents and grandparents! As Oscar Wilde said, "Children begin by loving their parents; as they grow older they judge them; sometimes they forgive them." In her essays and poetry, Dorothy has demonstrated all these attributes--love, judgment and forgiveness--with honesty and humor.

[1] Ralph Waldo Emerson, Representative Men Kindle Edition, p. 9.. Originally publiished in 1850 as a set of essays.

[2] Harvard University Archives, HUP Winslow, Samuel E.

[3} Adam Goodheart, 1861: The Civil War Awakening (New York: Vintage Books, 2012) pp.286-291.

[4] Harvard University Class of 1885 Secretary's Report VIII (1915), in Jim Moore and Natalie Vermilyea, Ernest Thayer's "Casey at the Bat:" Background and Characters of Baseball's Most Famous Poem (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1994), pp. 130-131

[5] John Richmond Husman, "J. Lee Richmond’s Remarkable 1879 Season," in The National Pastime Vol. 4, No .2, edited by John Thorn, Cooperstown, NY: The Society for American Baseball Research, 1985.

[6] Homer Croy, "Casey at the Bat," Baseball Magazine 1 (October 1908), pp 10-12. In his often sly fashion during interviews, Thayer downplayed his own knowledge of and interest in baseball, though his classmates did not agree. Winslow's teammate Roland Boyden wrote that baseball was a sport in which Thayer "took a deep interest," and that he acquired at Harvard "both a technical knowledge of the game and a great enthusiasm for it." (Harvard University Class of 1885 Secretary's Report (1935), pp. 357-358, 374-75.

The article "Sam Winslow vs. Mighty Casey," in Once-Told Tales of Worcester County by Albert B. Southwick, (Worcester, Chandler House Press, 1994) was provided by Dorothy Winslow Wright

3 comments

Read this article with interest. The Samuel Winslow home in Leicester, MA was located next door to the home of the Rev. Samuel May, Jr. home at #1 Main Street, Leicester. The Rev. S. May, Jr. was class secretary, Harvard University, Class of 1829. He was a well known abolitionist and women’s rights activist. His home was a stop on the Underground Railroad. His first cousin was Abba May Alcott, mother of the writer, Louisa May Alcott. Louisa May Alcott briefly lived in the Rev. S. May,Jr’s home as a young woman during a period when her mother had been ill and Alcott family members went to live with various family members. The Rev. S. May Jr.’s eldest son, Rear Admiral Edward May, grew up in the Leicester home. Twice during his naval career, he was stationed in Honolulu, Hawaii in the the late 1860’s and later, after he married, in the early 1870’s. He was a good friend of Gov. John Dominis, husband of Queen Liliuokalani, and was close to Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop and her husband Charles Reed Bishop. When his second tour of duty ended, he, his wife Mary and son Sam lived for a few weeks in the Dominis home, known later as Washington Place, after moving from their rental home, a few minutes walk away from the Dominis home, while awaiting the ship to arrive in Honolulu to take them to SAN Francisco. Their first born son, Samuel was born in Honolulu. In 1947, my parents were living at the S. May, Jr’s home and she witnessed the fire that destroyed the Winslow Home. She often told the story of how shocked and devastated she felt as this grand home burned to the ground. She said she was crying as she witnessed it. I and my 2 siblings lived at this Leicester home until 1954 when our family moved to Holden. My paternal grandparents lived in the home until their deaths in the mid 1960’s after which the home was sold to Becker Jr. College. Aloha, J. May, Mililani, Hawaii.

James May

Rich,

A fascinating and meticulously researched article. Your literary skills have never been more in evidence. Keep up the great work.

Abracos,

d

Dan Johnson

I’d say you hit a homer with the excellent research for this article. Who would have thought the story of “Casey at the Bat” went that deep?

Alan

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.