Pathos and Baseball: Revisiting "Casey at the Bat"

I think the popular focus on Casey and his strikeout, rather than on the victorious pitcher, illustrates the wisdom and poetic sensibility of crowds--i.e., recognizing the pathos of failure that is at the heart of baseball, even for the greats, and the pathos of the fan, who gives himself emotionally, freely, and without material self-interest.

-- Thomas W. Gilbert

Thomas W. Gilbert is the author of many baseball books, including How Baseball Happened, Baseball and the Color Line, Roberto Clemente, and Playing First. From his Greenpoint, Brooklyn stoop he can throw a baseball to the former site of the Manor House tavern, where members of the Eckford Baseball Club enjoyed a post game drink or two in the 1850s.

Tim Wiles, Baseball Hall of Fame director of research, portrays "The Mighty Casey." (Mike Groll/AP)

"There's no crying in baseball..." in the iconic line uttered by Tom Hanks in his role as manager Jimmy Dugan in the 1992 movie "A League of Their Own." Well, there may or may not be crying in baseball--but there is plenty of pathos.

I began Casey@theblog in 2019 to explore both the intriguing origins and what poet A. M. Juster has called "the long post-game show" of Ernest Thayer's 1888 ballad, "Casey at the Bat." This adventure has sometimes tempted me down less trodden byways, always starting as parallel tracks branching from the main theme. One of these has been the rediscovery of some of baseball's oldest poetry--in which I have benefited from the examples and guideposts provided by John Thorn, MLB's official historian. Another has been the exploration of heroic ballads of the pre-Civil War era which provided templates for the early bards of baseball, including young "Phinney" Thayer--nicknamed for his childhood idol, Phineas T. Barnum. But these divergent paths always wend their way back to "Casey's" main thoroughfare and ultimately lead forward to the enchanted intersection where history, baseball, myth, and poetry converge.

Most recently I was reminded of the classical elements of drama which baseball so often exemplifies (and which are effectively employed by "Casey's" classically-trained author to frame his own "Ballad of the Republic"). In a recent response to "The Ballad of Sam Winslow" posted on April 10, author Thomas Gilbert astutely observed that

...the popular focus on Casey and his strikeout, rather than on the victorious pitcher, illustrates the wisdom and poetic sensibility of crowds--i.e., recognizing the pathos of failure that is at the heart of baseball, even for the greats, and the pathos of the fan, who gives himself emotionally, freely, and without material self-interest.

Pathos! I was challenged by Gilbert's observation, which he allowed me to quote here, to revisit the emotions summoned by the ancient Greek tragedians--most notably, as in Aristotle's famous formulation of tragedy, the emotions of pity and fear. Wading through various interpretations of pathos (πάθος , in Greek) I am unable to say with conviction whether the Greeks intended their word to represent the intentional evocation of strong emotions, or the emotions themselves. But the Greeks seemed to have used the word in both a good and bad sense. In the New Testament, the apostle Paul unsurprisingly used the word only in a pejorative sense, in warnings to the Romans, Colossians, and Thessalonians, as in "depraved" or "vile" passions. (Leave it to St. Paul to take all the fun out of pathos!) As the word found its way into English usage in the 1500's, it came to signify both evocation and experience--not only the depictions of drama but also the audience's emotional reaction to what they witnessed.

George Santayana compared Thayer's humor to that of Mercutio in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet

But meandering back to "Casey:" pathos is an element Thayer consciously employed in his own writings--not just in his ballads penned for the San Francisco Examiner, but also in the light and rarely memorable verses he contributed to the Lampoon. This feature of Thayer's creativity was recalled by his fellow Lampoon contributor George Santayana more than five decades later.

Writing in 1943, Santayana recalled Thayer in his autobiography Persons and Places: "...he seemed a man apart, and his wit was not so much jocular as Mercutio-like, curious and whimsical, as if he saw the broken edges of things that appear whole, and a feeling...that the absurd side of things was pathetic."[1]

Santayana's observation that to Thayer, "the absurd side of things is pathetic," is significant. The English word pathetic descends from the Greek pathetos--subject to suffering--affecting or evoking pity or sorrow. It was an enduring characteristic of Thayer's writing that he would combine both absurdity and pathos: his sense of humor normally stirred the two together in equal measure.

"Casey" has also been cited by some critics to illustrate the very real but less-distinguished dimension of comedy that depicts suffering to evoke laughter. This aspect of humor undoubtedly traces back to the first homo sapiens taking the first pratfall in front of his fellows, and continues down to our present era as we, chuckle at the pool of shadow from the descending Acme anvil, spreading around the miserable figure of Wile E. Coyote, who at the last second, too late to save himself, glances upward with a look of infinite despair.

Eduardo Zamarcois y Sabala (1841-1871), "The Return to the Convent". Here the monks are enjoying the misfortunes of man vs. donkey: humor at the expense of others

"Schadenfreude" is a word consisting of antonyms paired by the Germans to indicate the mysterious bond linking sorrow and joy: specifically, the clandestine joy evoked by the sorrows and misfortunes of others. Finding pleasure in others' mishaps may not be one of humankind's nobler attributes but it is a steady source of humor in most cultures, and many commentators have suggested that it is one root of the enduring appeal of "Casey".

The actor De Wolf Hopper, the man who performed his solo recitation of "Casey," by his own count, more than ten thousand times, single-handedly transformed Casey from a back-page newspaper oddity into the great American ballad. Hopper held "Casey" to be the great American comic poem. "It is as perfect an epitome of our national game today as it was when every player drank his coffee from a mustache cup....there is no day in the playing season that this same supreme tragedy, as stark as Aristophanes for the moment {emphasis mine} does not befall on some field."[2]

With his training as an actor, Hopper understood that the roots of the enduring appeal of "Casey" were classical-- but did he know his Greek playwrights? Did Hopper not realize that Aristophanes was the great comic poet of the Greeks--the author of The Wasps, The Frogs, and Lysistrata. Perhaps, Hopper meant to say "...as stark as Aeschylus." Aeschylus (ca 525/524 - ca 456/455 BC) was the first and greatest of the Greek dramatists, one of the survivors of the epic battle of Marathon, in which a handful of Athenian warriors had defeated the mighty Persian army.

Classicist and author Edith Hamilton, 1867-1963

Aeschylus, according to Edith Hamilton, "knew life as only the greatest poets can know it; he perceived the mystery of suffering. Mankind he saw fast bound to calamity by the working of unknown powers, committed to a strange venture, companioned by disaster. But to the heroic, desperate odds fling a challenge...The fullness of life is in the hazards of life. And, at the worst, there is that in us which can turn defeat into victory."[3] This was the wisdom of the Greeks, which Americans in the year 1888 professed to admire--but the actual behavior of the Mudville multitude (as "Casey" teaches us) was much more akin to that of the Romans, who demanded victory above all.

Yet Hopper, citing Aristophanes, may have had it right after all: it was Aristophanes to whom Plato attributed the sublime dramatic insight, often quoted by Churchill: "The qualities required for writing tragedy and comedy are the same, and a tragic genius must also be a comic genius."[4] Hopper himself applied this axiom to acting. In his autobiography, in a comment on Shakespearean actor Edwin Booth (1833-1893), whom Hopper held in high regard, he wrote:

"...No man ever was a truly great tragedian who lacked the comic sense. I doubt that a man ever reached the full measure of greatness in any vocation without that saving grace of humor."[5]

Aristophanes c. 446 - c. 386 BC

There is tragedy, there is comedy--and there is pathos. Here again, baseball commentators have often belittled or misread the tragedy embedded in "Casey." Bill Littlefield, host of National Public Radio's "Only a Game," aired a retrospective of the immortal poem on February 27, 2016 under the title "Poetry and Baseball: Revisiting 'Casey at the Bat'." "Ernest Lawrence Thayer may not have been a great poet," opined Littlefield, "but he understood the nature of myth well enough to know that it’s the fate of heroes to take on one-too-many dragons....It makes a terrible kind of sense, just as tragedy is meant to do."

Bill Littlefield -- author, educator, broadcaster of NPR's "Only A Game"

So far, so good. For tragedy, in its classical form, is meant to lift us out of the commonplace cussedness of circumstance, and to evoke within us the sublime realization, the "terrible kind of sense" as Littlefield expressed it, that the outcome of the drama could not have been otherwise. But when Littlefield claimed that "'Casey at the Bat'" is not tragedy, It’s pathos," I felt I had to disagree. For pathos (I believed) is not just some bargain-rack version of tragedy.

In retrospect I've come to understand what I think Littlefield wanted us to learn from "Casey," and what Thomas Gilbert suggests in his introductory epigram about pathos in baseball. (Coincidentally, both Gilbert and Littlefield are Yale graduates--Gilbert studied Classics and Classical Languages, Littlefield went on to teach English for 39 years at Curry College and to host NPR's "Only A Game"). Tragedy--I believe now--is what happens "on the field"--or on the stage, so to speak. Only the players--the protagonists--can truly experience tragedy first-hand. For the rest of us who witness the action on the field (or on stage)--we experience the pathos of the moment, we feel the pity and fear (in Aristotle's formula); we are cast down and we are exalted -- but our experience, in comparison with those of the players on the field, is categorically different.

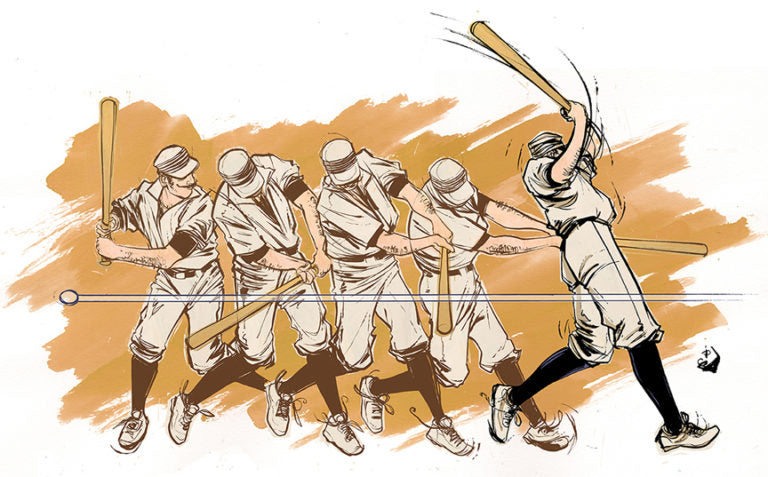

A key element of Greek tragedy: a man neither good nor bad brought low by hubris. Illustration by Dan Sayre Groesbeck from the 1912 edition of "Casey at the Bat" (Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co.)

Thayer's brand of humor elevated the duel between slugger and spinner by placing it within the classical framework of Greek tragedy--employing all the classical elements of hubris, peripeteia (the sudden reversal of fortune), and anagnorisis (the sudden recognition, or "knowing back" as Bernard Knox has translated it). Think of Casey in the penultimate stanza of the poem giving way to this recognition, angrily pounding his bat on the plate and realizing that he should never have window-shopped those previous two strikes. In this way Casey fulfills Aristotle's definition of the tragic character "between these two extremes--that of a man who is not eminently good and just, yet whose misfortune is brought about not by vice or depravity, but by some error or frailty."[6]

Poet-laureate Donald Hall (1928-2018) wrote of "Casey" in 1888, "For a hundred years this mock heroic ballad has lurked alive at the edges of American consciousness."

"Elevation is fundamental" said poet Donald Hall of "Casey," for it lifts a commonplace occurrence in baseball to the height of human experience. This kind of elevation defines the genre of "mock-heroic." And though "Casey's" strikeout--in the great scheme of human affairs, or even of the seasonal cycle of baseball--is fictional, the emotions evoked by the drama of sports are undeniably real. We, the audience, or the fans, experience the "pathos of failure that is at the heart of baseball" (in Gilbert's words) over and over again. Of the 30 major-league teams in the U.S., the fans of 29 of them will eventually experience some degree of pathos as their hopes come to an end. I felt the pangs of pathos this week, as the Reds returned from a four-game sweep of the Cardinals only to drop two out of three to the Brewers at home. Then the Rockies arrived, and the Reds bombarded them 11-5. For now, pathos is in abeyance.

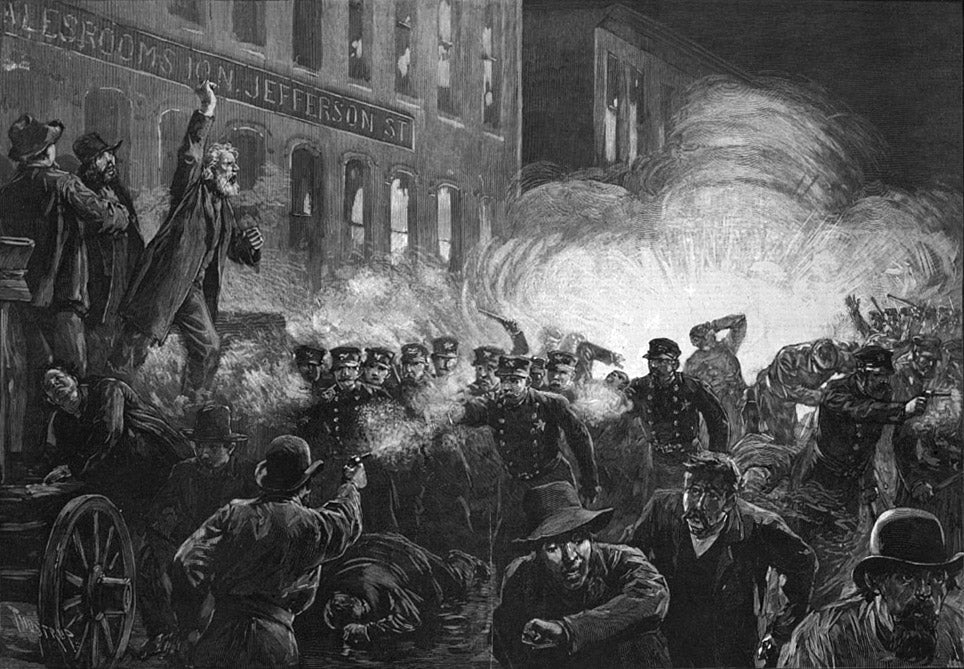

A key element of tragedy employed by Thayer is the effect on the community itself. Illustration by Dan Sayre Groesbeck for the 1912 edition of "Casey at the Bat" (Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co., 1912).

So Thayer in his witty, irreverent way, turned Thomas Macaulay on his head (and in the process wrote a far better poem than "Casey's" predecessor "Horatius") by simply holding Casey answerable to the gods for his own fate. And in classical terms, Thayer's "Casey" did not fail to include a capstone element of classical tragedy--the effect of pathos as shared by the community as a whole. As Leonard Conversi and Richard Sewall remind us, in their Encyclopedia Britannica article:

Whatever the original religious connections of tragedy may have been, two elements have never entirely been lost: (1) its high seriousness, befitting matters in which survival is at issue and (2) its involvement of the entire community in matters of ultimate and common concern. When either of these elements diminishes, when the form is overmixed with satiric, comic, or sentimental elements, or when the theatre of concern succumbs to the theatre of entertainment, then tragedy falls from its high estate and is on its way to becoming something else.[7]

The stage at Wallack's Theatre on Broadway where "Casey at the Bat" was first performed by De Wolf Hopper on August 14, 1888

The stage at Wallack's Theatre on Broadway where "Casey at the Bat" was first performed by De Wolf Hopper on August 14, 1888

Ernest Thayer's classmate George Santayana wrote an 1894 essay ("Philosophy on the Bleachers") about the inherent drama evoked by all athletic contests. Santayana noted (as did Thayer, in "Casey" ) "...the frenzy of joy of the thousands upon one side and the grim and pathetic silence of the thousands upon the other." Yet Santayana did not scorn this frenzy: "I cannot feel," he wrote in his elegant, backhanded style, "that the passion is excessive."

George Santayana 1863-1952. George shared with classmate Ernest Thayer a love of sports. But George, unlike Thayer, was primarily a football fan.

"Is there not some pent-up energy in us," asked Santayana, "some thirst for enjoyment and for self-expression, some inward rebellion against a sordid environment, which here finds inarticulate expression? Is not the same force ready to bring us into other arenas, in which, as in those of Greece, honour should come not only to strength, swiftness, and beauty, but to every high gift and inspiration?"[8]

Harvard Base-Ball nine, 1884 season. Though the photo is undated, the expressions suggest it was most likely taken following the team's 2-4 loss to Yale in a one-game championship playoff in Brooklyn's Washington Park on June 27

Michael Crampton for the National Pastime Museum

Perhaps, after all, it is only fair to let Bill Littlefield have the last word--illustrating perhaps that one of the best ways we mortals have of reckoning with pathos is through the medium of poetry:

Oh somewhere in this favored land the sun is shining bright.

But Mudville’s gloom ain’t permanent; folks there have got it right:

The fact that Casey let them down won’t really change a lot.

The Nine of Mudville? As a team, they’ve never been so hot,

And whether they have lost or won, as dark gives way to dawn…

The citizens of Mudville rise each day and soldier on.

Notes:

On the modern distinction between pathos and tragedy see Warwick Wadlington, "The Sound and the Fury: A Logic of Tragedy," in On Faulkner, edited by Louis J. Budd, Edwin Harrison Cady, in series The Best from American Literature (Durham: Duke University Press, 1989), pp. 128-142.

"In the post-Enlightenment, pathos has become the term of contra-distinction to tragedy. According to the most widespread view, tragedy involves suffering that results mainly from the protagonist's action, which is usually persistent, decisive—heroic. The mode of pathos, by contrast, is said to involve a relatively passive suffering, not springing from action but inflicted by circumstances. In terms of the linked root meanings of pathos (passion, suffering), tragedy is held to be pathos resulting from heroic action."

[1] George Santayana, Persons and Places (New York: Scribner, 1943), p. 197.

[2] DeWolf Hopper, in Once a Clown, Always a Clown

[3] Edith Hamilton, The Greek Way

[4] Winston Churchill,

[5] Hopper, ibid.,

[6] Aristotle (S. H. Butcher, translator), The Poetics of Aristotle (Macmillan, 1902), quoted by Bernard Knox, translator and commentator, in Oedipus the King, by Sophocles (New York: Pocket Books, Simon& Schuster, Inc.), 1994, pp. 109-110.

[7] Conversi, Leonard W. and Sewall, Richard B.. "Tragedy". Encyclopedia Britannica, 13 Nov. 2020, https://www.britannica.com/art/tragedy-literature. Accessed 19 May 2021.

[8] George Santayana, "Philosophy on the Bleachers,"

Cover Illustration Credit: P. J. Loughran, commissioned for the National Pastime Museum

#pathos #CaseyattheBat #BalladoftheRepublic #baseball #ErnestThayer #ThomasGilbert #BillLittlefield #Mudville

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.