The Raving: A Visit from Old Nick

Official Announcement--2024 Award Winners, International Edgar Allan Poe Festival & Awards

In 2024, "The Raving: A Visit from Old Nick" was nominated for the sixth annual Saturday "Visiter" Awards, a feature of the International Edgar Allan Poe Festival & Awards in Baltimore, Maryland, October 4-6, 2024. On October 5, at the awards ceremony, "The Raving" was named as one of three co-equal winners in the "Original Works" category. Baltimore artist Connie Matricardi received the award on behalf of "Caseyatthe.blog" and her fellow Peace Corps (Brazil) colleague, author Rich Davis. (See Connie's artwork, below!)

Edgar Allan Poe, portrait by Constance Matricardi (2023)

About Poe, Dickens, and the “Christmas Crawler”

Elsewhere in Caseyatthe.blog I've described my motivation in revisiting American poems of the 19th century, and my whimsy in re-imagining Ernest Lawrence Thayer’s baseball ballad as the 19th century’s greats (Whitman, Dickinson, and Poe) might have written it. In 2023, this blog’s tribute to Poe (“Casey in Ulalysium”) was a nominee for the 5th annual Saturday “Visiter” Awards, presented by Poe Baltimore as part of the Poe International Festival. My 2025 submission deviated from the blog’s dominant motif as an investigation of Ernest Thayer and his “Casey at the Bat” to explore the literary origins of, and influences embedded in Poe’s most famous creation, “The Raven.”

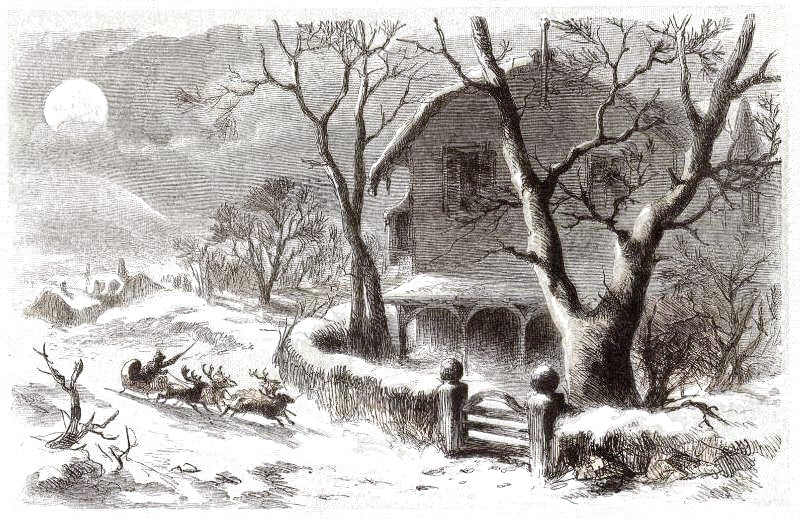

This illustration by American illustrator and engraver F. O. C. Darley from an 1862 printing of "A Visit from St. Nicholas" transforms the cozy domesticity of the original poem into a sinister landscape

Historical and Literary Context

In England, the era that began in 1837 with the crowning of Queen Victoria experienced a revival of interest in Christmas traditions and festivities. In America at the same time, the transition to a modern secular Christmas was already well underway—merging earlier versions of Saint Nicholas, the Dutch Sinter Klaas, and even pre-Christian figures such as Odin, riding his white horse accompanied by two ravens who listened at the rooftops to report on the behavior of mortals in the households below. This amalgamation of Christian and pre-Christian figures into the modern Santa Claus was propelled by “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” published on December 23, 1823 and generally attributed to Clement Clarke Moore, a scholar and professor in New York City.

"Old Christmas, riding a goat," (1836) by Robert Seymour

The figure of “Old Christmas,” (1836) by English illustrator Robert Seymour for The Book of Christmas by Thomas Kibble, hints at the pre-Christian version of a Yuletide visitor. With his Dionysian leer, a bowl of wassail, and even (it appears) a naughty child tucked under an arm, this version of “Old Nick” reflects the ancient Roman Saturnalia and the medieval "Lord of Misrule" chosen to lead the Christmas revels. (Sadly, only months after producing this image, Seymour died by his own hand after an argument with the young Charles Dickens over illustrations for the Pickwick Papers).

In the time of Henry VII of England (1485-1509) the Lord of Misrule presided over the Twelve Days of festivities

Another illustrator was soon found to complete the drawings for Pickwick Papers—the talented “Phiz” (Hablot K. Browne). By the time of publication in 1837, Phiz had drawn the unearthly visitors for a fantastic Christmas Eve tale imagined by Dickens for the Pickwick Papers—“The Goblins Who Stole a Sexton.” The “morose and lonely” old gravedigger is interrupted at his work by a troupe of goblins who show him scenes of Christmas as celebrated by poor and humble families who embody the true spirit of the season. It was a theme to which Dickens would return in 1843.

“The Goblin and the Sexton” by “Phiz” (1837) illustrating the Christmas eve story from Dickens's first novel, Pickwick Papers

By this and other popular Yuletide stories of ghosts and goblins the Victorian tradition of the “Christmas crawler”--often serialized in newspapers--was well established by the time Dickens turned his hand to the tale of Ebenezer Scrooge. Published the week before Christmas in 1843, by the end of 1844 the tale of Scrooge's ghostly Christmas Eve visitations had gone through 13 printings and was becoming as popular in the United States as it was in Britain.

John Leech illustration, “The Second of Three Visitors” for the 1st edition of Dickens's "A Christmas Carol"

Could there be any doubt that when Edgar Allan Poe imagined his own tale set in a “bleak December,” encountering an unearthly visitor whose mysterious origins evoke either “the saintly days of yore”--or more ominously “the night’s Plutonian shore”-- he was well aware of the spectral visitors haunting the Yuletide tales of Charles Dickens? For Poe’s own account of his creation of “The Raven” (his essay "The Philosophy of Composition") hints that he derived the notion of his avian emissary from the talking bird in another Dickens tale, Barnaby Rudge.[1]

"Grip," the pet Raven of the Charles Dickens family (after taxidermy in 1841). The raven in Dickens's Barnaby Rudge, also named Grip, is generally considered to have been the inspiration for Poe's "The Raven"

Google search results for Poe's poem "The Raven," outpace those of every other single American poem--including that of the Christmas Eve visit of the "jolly old elf." There is a mysterious connection between these two airborne visitors competing in web search popularity: Nicholas, illuminated by his ancient aura of sainthood, and the shadowy corvid, like St. Nick making his appearance in the "bleak December," bringing with him a reminder of the "saintly days of yore." But the spectral raven's place in Norse mythology, and the poetic suggestion that the bird may be an emissary of Pluto, the Roman god of the underworld, soon lead the "Raven's" narrator to a foul suspicion: "Thing of evil," he cries, " If bird or devil / Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore..." This ambiguity is not resolved in "The Raven," which led me to imagine an unambiguous version of "A Visit from St. Nicholas" as Poe might have reinterpreted the scene--or as he might have ventured a commentary upon the pernicious commercialism which by1845 had already begun to transmogrify the festive season.[2]

Christmas ad from Newburyport, Massachusetts Herald, Jan. 3, 1849, illustration in Paul R. Spitzzeri, "The Evolution of Christmas in the Late 1840's," in The Homestead Blog (Dec. 1, 2016) of the Homestead Museum, Los Angeles. Spitzzeri describes this Santa-like figure as "maniacal, with a wolf-like face [and] wild eyes."

The literary connection between the aerial arrival of these unannounced December visitors poses a face-off between Saint Nick and "Old Nick." The latter in various definitions is a jocular or colloquial reference to the devil (some authorities place the phrase's origin in the Dutch word "Nikken," meaning "the Devil"). The juxtaposition of the saintly and demonic in ancient Yuletide traditions is well known, as in the folklore of alpine regions of Austria and Bavaria, where Saint Nicholas is accompanied on his rounds by the Krampus, a predatory character whose role is that of chastising or even carrying off naughty children.

Political cartoonist Thomas Nast's 1864 illustration of the "jolly old elf" about to make another unannounced appearance, in Christmas Poems and Pictures (1864)

Here, then, is a version of the poem Americans have come to know as “'Twas the night before Christmas…”-- as Edgar Allan Poe might have scripted it in January 1845.

The Raving: A Visit from Old Nick

‘Twas night before a Yuletide dreary, as I nodded, napping nearly,

From the hearth each dying ember cast a spectral shadow on the floor;

No creature in the house was stirring, nor furtive foot-fall softly scurrying,

While flakes of snowfall came a-flurrying, the sleet and seeping slush a-slurrying,

As wild and wintry winds a-hurrying through the towering tempest tore--

Only that, and nothing more.

When suddenly there came a pattering, upon the rooftop came a clattering,

A battering and spattering where there had been none before;

“Is this something to be mattering?” I wondered idly nattering—

“Or merely ice-bound branches shattering and scattering

Upon the night’s Plutonian shore?

Is this all, or something more?”

Ah, distinctly I remember, it was in the bleak December,

When the season’s sad distemper spread its shadow ‘round my door –

Though the tempest fell to ceasing, I could hear the din increasing:

“There’s a scraping now escaping from the chimney-stack!” I swore;

Smoke now came a-choking--from the smoldering hearth it poured—

Then from out the conflagration of my wild imagination

Stepped a figure nameless here--forevermore.

I gaped as one untutored as from horn to hoof accoutered

In vermilion he was suited, springing nimbly to his chore:

He unbuckled and uncinched the battered bag he clinched,

Spreading packages beribboned and bedizened on the floor;

With many a blighted item--their encumbrance uninvited,

Whether then or evermore!

Then with his purse a-jingling, he frowning stood a-fingering

A sheaf of papers scavenged from the leather pack he bore;

“Here I hold the bill of lading,” read he; “Common article of trading,” said he;

Then unscrolled a list of purchases I had never seen before—

A pestilence of procurements I had never seen before—

All undesired – from then to evermore!

"A pestilence of procurements..." blue-coated Santa figure delivering biscuits for Wm H. Zinn Stores, Boston (trade card, mid-1800's)

“Who art thou, émissaire du ciel ou de l'enfer,*

To be shedding, spreading the detritus from thy pack upon my floor?

Whence the sender that hath sent thee?” Thus I sought some swift nepenthe—

Desperate respite from suspicions that were burrowing through my core—

Foul the furrowing of suspicions which I could not then ignore;

Neither then nor evermore!

"Wherefrom such dire abundance...." Exhausted Santa figure checking his delivery book (Victorian-era trade card)

“Tell me then, mysterious stranger, wherefrom such dire abundance;

I fear the danger of such indulgence as you have here conveyed;

For this delivery I cannot recompense you—but I have a sense you

Have been misdirected by one known oft to leave her debts unpaid—

By one who now is vanished, ever banished from my door--

By one who bides not here—not anymore!”

Within my heart all hope was fading—calamity now came cascading—

And my demons now came raiding where they never rode before:

Just as I feared, that fell magician then displayed the dread inscription

And demanded recognition—the affliction of the temptress

whom the goblins named “Lenore:”

Cognomen of my nemesis—that impecunious temptress

whom the goblins named “Lenore.”

Gustave Doré's illustrations of "The Raven" are haunted by the shadow of "the lost Lenore," whose residual influences are scarcely benign

"Though you may decline possession," quoth the stranger, subtly smiling,

"You may yet escape transgression." Whispering then, he turned beguiling--

“Our ancient firm has a tradition--requiring only your decision:

You may retain, in perpetuity, all this largesse--as our gratuity—

With merely one condition (which I was deficient in not mentioning heretofore):

Your signature--as receipt sufficient--(on this line here) forevermore!”

Some deviance in the countenance of this apparition

Now gave me strength to formulate my opposition—

The bargain that he offered seemed too generous, by far—

And the document he proffered in some hieroglyphic script was authored

In an arcane tongue I recognized from ancient books of lore:

“Tempter!” then I shrieked, “Foul fiend, begone—forevermore!”

Then in a trice, within a cloud of sulphur swirling,

Mephitic smoke-rings ‘round his malicious visage whirling--

That old blasphemer, then to the blazing hearth retreating

Ascended with a final apothegm repeating:

“Yule can be cruel to whom its perils they ignore--

But now from this abode, I shall abscond…forevermore!”

--“A Visit from St. Nicholas,” attributed to Clement Clarke Moore (1779-1863), as might have been penned by Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) – as imagined by Richard Collins Davis.

* ...émissaire du ciel ou de l'enfer: "emissary of heaven or hell." Poe learned French at a boarding school during a period of his boyhood in England, but he never actually visited France. The introduction of his works to the French was the passion of poets Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) and Stéphane Mallarmé (1842-98), whose translations of "The Raven" and other works brought Poe a posthumous fame in France which has never faded. If there is ever an attempt to translate "The Raving: A Visit from Old Nick," as might have been penned by Baudelaire or Mallarmé, I can only vow, as repeated by the infamous Corbeau: "Jamais plus!."

"Be that word our sign of parting..." from Gustave Doré (1832-1883) illustrations for "The Raven" (published 1884)

Author’s Note: I was entranced with the idea of poetic influence when I first encountered Professor Harold Bloom’s notion that every poem is a reflection of, or in some way a response to, a predecessor poem. Bloom’s Anxiety of Influence made me aware that works of literature, from Shakespeare to Tolkien, all draw upon predecessor legends, ballads, myths, and their associated characters and images in some way – an insight that I have applied to my understanding of 19th-century baseball poetry and of “Casey at the Bat” in particular.

Oscar Wilde said, "Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery..." but few recall his entire witticism: "Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery that mediocrity can pay to greatness." George Bernard Shaw rephrased the thought by removing the sting of it: "Imitation is not just the sincerest form of flattery, it is the sincerest form of learning." So should I ever encounter in some tenebrous vale of the Elysian Fields the shades of oft-emulated poets Edgar Allan Poe and Clement Clarke Moore, I trust they would perceive no malice in my modest mimicry.

For those curious as to how other prominent 19th-century American poets might have misappropriated Ernest Thayer's immortal baseball ballad, see Emily Dickinson in the Elysian Fields and Song of Our Game: The Ballad of Casey as Imagined by Walt Whitman. Similarly, the Poe-tic version can be found in "Casey in Ulalysium" within this blog. Then you may be fortified for Casey Stops by the Ball Park on a Snowy Evening as imagined by Robert Frost.

A final question should be asked and answered: did Poe have a sense of humor? At least one scholar, Daniel Royot (Emeritus Professor at the Sorbonne) affirmed that “Poe was also a born humorist equally inspired by parody and self-mockery.” Poe’s writings featured hoaxes, satire, explorations of the absurd, and extravagant narrations—often within the framework of an author claiming to be mere recorder of a tale told by another. And of course we recognize in Poe’s tales the “black humor” characterized by Royot as a form of bravado designed to articulate genuine fears or to allay such fears.

Another French scholar, Rene Girard, observed that the demonic figure in ancient myths who crossed over from hell to harass humans was, over time, transformed into a comic denizen (as a Mephistopheles evolved into “Old Nick”). As Royot puts it, “Ancestral terror has gradually been changed into farcical profanity and aggressiveness into merrymaking. So do the tales allowing Poe a comic relief by staging the absurd contradictions of a Janus figure impersonating both the clown and the genial transgressor who challenge dogma and induce a cheerful nihilism.”[3]

[1] Kevin J. Hayes and Richard Kopley, in their chapter "Two Verse Masterworks: 'The Raven' and 'Ulalume'" in The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe (Cambridge University Press, 2002, 191-204) suggest that "...the raven had been encouraged by Poe's encounter with the raven in Charles Dickens's novel Barnaby Rudge. Poe had reviewed the book in 1841 and 1842: he first stated that the raven's 'croakings are to be frequently, appropriately, and prophetically heard in the course of the narrative,' but he later shifted his view, wishing that its 'croakings might have been prophetically heard in the course of the drama'." In their article, Hayes and Kopley also cite and promote a widely-held view that "The Raven" and "Ulalume" are Poe's two best poems.

[2] See the perceptive essay by Penne Restad, "Christmas in 19th Century America" in History Today (Volume 45, Issue 12, December 1995):

Gift-giving itself became controversial, sometimes perceived as a worrisome, materialistic perversion of a holy day. Such fear has not stemmed the growth of Christmas commerce. Indeed, by our own day, Christmas gift-giving has become the single most important sector of the consumer economy. No wonder that some have read backwards in time to make the new Christmas almost a conspiracy of retailers. Yet evidence suggests that the transition to a Christmas economy occurred only gradually, with both merchant and consumer acting as architects. In the 1820s, '30s and '40s merchants had noticed the growing role of gifts in the celebration of Christmas and New Year. Starting in the mid- to late- 1850s, imaginative importers, craftspersons and storekeepers consciously reshaped the holidays to their own ends even as shoppers elevated the place of Christmas gifts in their home holiday. However, for all the efforts of businessmen to exploit the season. Americans persistently attempted to separate the influence of commerce from the gifts they gave.

See also Restad's article "America's Deep Roots of Christmas Commercialism," in The Dallas Morning News (December 15, 2015): "These days, it is a commonplace to say that the economy depends on Christmas sales and that marketing strategies, such as Black Friday, threaten the holiday of yore...But less often noted is that the market revolution of the 19th century, and the consumer economy it created, made possible and continues to sustain what we mean when we talk about the 'spirit of Christmas'.”

[3] See for these observations by Daniel Royot, who cites Rene Girard, “Poe’s Humor,” in The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe, op. cit., pp. 57-71.

#TheRaven #EdgarAllanPoe #'TwastheNightBeforeChristmas #ClementClarkeMoore #SantaClaus #AVisitfromSt.Nicholas #OldNick #FatherChristmas #SaintNicholas #Krampus #PoeFestivalInternational #PoeBaltimore #Caseyatthe.blog #CaseyattheBat #SaturdayVisiterAwards #CharlesDickens #AChristmasCarol #PoeFestInternational.org #PoeFestInternational.com

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.